Acoustic tweezers

[3] The target object must be considerably smaller than the wavelength of sound used, and the technology is typically used to manipulate microscopic particles.

[citation needed] Acoustic waves have been proven safe for biological objects, making them ideal for biomedical applications.

[5] The use of one-dimensional standing waves to manipulate small particles was first reported in the 1982 research article "Ultrasonic Inspection of Fiber Suspensions".

[7] Yosioka and Kawasima calculated the acoustic radiation force on compressible particles in a plane wave field in 1955.

[8] Gorkov summarized the previous work and proposed equations to determine the average force acting on a particle in an arbitrary acoustical field when its size is much smaller than the wavelength of the sound.

[12] The viscous effects on the secondary acoustic force can become significant when compared to the perfect fluid formulation exemplified above, and even dominant in certain limit cases, yielding both quantitatively and qualitatively different results than what is predicted by inviscid theory.

[13] The relevance of the viscous contributions varies greatly depending on the specific case being investigated, and thus important care needs to be taken in selecting an appropriate secondary acoustic force model for the given scenario.

It becomes important in aggregation and sedimentation applications, where particles are initially gathered in nodes by the acoustic radiation force.

As inter-particle distances become smaller, the secondary forces assist in further aggregation until the clusters become heavy enough for sedimentation to begin.

[14][15] Eckart streaming is driven by a time-average momentum flux created when high-amplitude acoustic waves propagate and attenuate in a fluid.

Those first-order terms, however, being pure sines, in a quasi-steady state, repeat after each oscillation cycle, yielding no net fluid flow.

Second-order terms, instead, are not harmonic, and thus can have a cumulative effect which, despite being smaller, can add up over many oscillation cycles, leading to the development of the net steady-state flow we identify as acoustic streaming.

By applying Newton's law, the motion can be described as: where For applications in a static flow, the fluid velocity comes from the acoustic streaming.

The magnitude of acoustic streaming depends on the power and frequency of the input and the properties of the fluid media.

Shi et al. reported using interdigital transducers (IDTs) to generate a standing surface acoustic wave (SSAW) field with pressure nodes in the middle of a microfluidic channel, separating microparticles with different diameters.

Once an RF signal is applied to both IDTs, two series of surface acoustic waves (SAW) propagate in opposite directions toward the particle suspension solution inside the microchannel.

Leakage waves in the longitudinal mode are generated inside the channel, causing pressure fluctuations that act laterally on the particles.

The tunability offered by chirped[clarification needed] interdigital transducers[25][26] renders it capable of precisely sorting cells into a number (e.g., five) of outlet channels in a single step.

To meet the resolution requirements of manipulating single cells, short-wavelength acoustic waves should be employed.

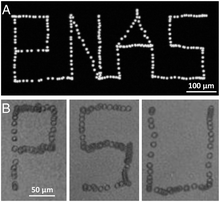

[28] Figure 6 records a demonstration that the movement of single cells can be finely controlled with acoustic tweezers.

Ding et al. employed chirped interdigital transducers (IDTs) that are able to generate SSAWs with adjustable positions of pressure nodes by changing the input frequency.

In this approach, SSAWs are generated by interdigital transducers, which induced a periodic alternating current (AC) electric field on the piezoelectric substrate and consequently patterned metallic nanowires in suspension.

By controlling the distribution of the SSAW field, metallic nanowires are assembled into different patterns including parallel and perpendicular arrays.

[35] Since many particles of interest are attracted to the nodes of an acoustic field and thus expelled from the focus point, some specific wave structures combining strong focalization but with a minimum of the pressure amplitude at the focal point (surrounded by a ring of intensity to create the trap) are required to trap this type of particle.

These specific conditions are met by Bessel beams of topological order larger than zero, also called "acoustical vortices".

With this kind of wave structures, the 2D[36] and 3D[37][38] selective manipulation of particles has been demonstrated with an array of transducers driven by programmable electronics.

[39] The individual selective manipulation of micro-objects requires to synthesize complex acoustic fields such as acoustic vortices (see previous section) at sufficiently high frequency to reach the necessary spatial resolution (typically the wavelength must be comparable to the size of the manipulated object to be selective).

Many holographic methods have been developed to synthesize complex wavefields including transducer arrays,[40][41][36][42][38] 3D printed holograms,[43] metamaterials [44] or diffraction gratings.

[45][46] Nevertheless, all these methods are limited to relatively low frequencies with an insufficient resolution to address micrometric particles, cells or microorganisms individually.

On the other hand, InterDigitated Transducers (IDTs) were known as a reliable technique to synthesize acoustic wavefields up to GHz frequency.