Coelacanth

Others, see text Coelacanths (/ˈsiːləkænθ/ ⓘ SEE-lə-kanth) (order Coelacanthiformes) are an ancient group of lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii) in the class Actinistia.

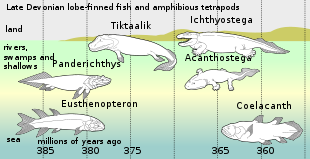

[2][3] As sarcopterygians, they are more closely related to lungfish and tetrapods (which includes amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals) than to ray-finned fish.

Coelacanths were thought to have become extinct in the Late Cretaceous, around 66 million years ago, but were discovered living off the coast of South Africa in 1938.

[9][10][11] The word Coelacanth is an adaptation of the Modern Latin Cœlacanthus ('hollow spine'), from the Ancient Greek κοῖλ-ος (koilos, 'hollow') and ἄκανθ-α (akantha, 'spine'),[12] referring to the hollow caudal fin rays of the first fossil specimen described and named by Louis Agassiz in 1839, belonging to the genus Coelacanthus.

[15] On 22 December 1938, the first Latimeria specimen was found off the east coast of South Africa, off the Chalumna River (now Tyolomnqa).

"[6] Its discovery 66 million years after its supposed extinction makes the coelacanth the best-known example of a Lazarus taxon, an evolutionary line that seems to have disappeared from the fossil record only to reappear much later.

The tail is very nearly equally proportioned and is split by a terminal tuft of fin rays that make up its caudal lobe.

At the back of the skull, the coelacanth possesses a hinge, the intracranial joint, which allows it to open its mouth extremely wide.

The parallel development of a fatty organ for buoyancy control suggests a unique specialization for deep-water habitats.

Despite prior studies showing that protein coding regions are undergoing evolution at a substitution rate much lower than other sarcopterygians (consistent with phenotypic stasis observed between extant and fossil members of the taxa), the non-coding regions subject to higher transposable element activity show marked divergence even between the two extant coelacanth species.

[46] Mimipiscis (Actinopterygii) Porolepis (Porolepiformes) Miguashaia Styloichthys Gavinia Diplocercides Serenichthys Holopterygius Allenypterus Lochmocercus Polyosteorhynchus Rebellatrix Hadronector Rhabdoderma Caridosuctor Sassenia Spermatodus Piveteauia Coccoderma Laugia Coelacanthus Guizhoucoelacanthus Wimania Axelia Whiteia Heptanema Dobrogeria Atacamaia Luopingcoelacanthus Yunnancoelacanthus Chinlea Parnaibaia Trachymetopon Lualabaea Axelrodichthys Mawsonia Garnbergia Diplurus Megalocoelacanthus Libys Ticinepomis Foreyia Holophagus Undina Macropoma Swenzia Latimeria According to the fossil record, the divergence of coelacanths, lungfish, and tetrapods is thought to have occurred during the Silurian.

[51] The most recent fossil latimeriid is Megalocoelacanthus dobiei, whose disarticulated remains are found in late Santonian to middle Campanian, and possibly earliest Maastrichtian-aged marine strata of the Eastern and Central United States,[52][53][54] the most recent mawsoniids are Axelrodichthys megadromos from early Campanian to early Maastrichtian freshwater continental deposits of France,[55][56][49] as well as an indeterminate marine mawsoniid from Morocco, dating to the late Maastrichtian[57] A small bone fragment from the European Paleocene has been considered the only plausible post-Cretaceous record, but this identification is based on comparative bone histology methods of doubtful reliability.

[46] The current coelacanth range is primarily along the eastern African coast, although Latimeria menadoensis was discovered off Indonesia.

Coelacanths have been found in the waters of Kenya, Tanzania, Mozambique, South Africa, Madagascar, Comoros and Indonesia.

[59] Most Latimeria chalumnae specimens that have been caught have been captured around the islands of Grande Comore and Anjouan in the Comoros Archipelago (Indian Ocean).

Though there are cases of L. chalumnae caught elsewhere, amino acid sequencing has shown no big difference between these exceptions and those found around Comore and Anjouan.

[8] Mitochondrial DNA sequencing of coelacanths caught off the coast of southern Tanzania suggests a divergence of the two populations some 200,000 years ago.

[62] Key components confining coelacanths to these areas are food and temperature restrictions, as well as ecological requirements such as caves and crevices that are well-suited for drift feeding.

[63] Teams of researchers using submersibles have recorded live sightings of the fish in the Sulawesi Sea as well as in the waters of Biak in Papua.

The islands' underwater volcanic slopes, steeply eroded and covered in sand, house a system of caves and crevices which allow coelacanths resting places during the daylight hours.

[68] Coelacanths are ovoviviparous, meaning that the female retains the fertilized eggs within her body while the embryos develop during a gestation period of five years.

The male coelacanth has no distinct copulatory organs, just a cloaca, which has a urogenital papilla surrounded by erectile caruncles.

This was only discovered when the American Museum of Natural History dissected its first coelacanth specimen in 1975 and found it pregnant with five embryos.

[7] A study that assessed the paternity of the embryos inside two coelacanth females indicated that each clutch was sired by a single male.

The IUCN currently classifies L. chalumnae as "critically endangered",[71] with a total population size of 500 or fewer individuals.

In the 1980s, international aid gave fiberglass boats to the local fishermen, which moved fishing beyond the coelacanth territories into more productive waters.

Since then, most of the motors on the boats failed, forcing the fishermen back into coelacanth territory and putting the species at risk again.

The CCC has branches located in Comoros, South Africa, Canada, the United Kingdom, the U.S., Japan, and Germany.

Their scales themselves secrete mucus, which combined with the excessive oil their bodies produce, make coelacanths a slimy food.

[82] Because of the surprising nature of the coelacanth's discovery, they have been a frequent source of inspiration in modern artwork, craftsmanship, and literature.