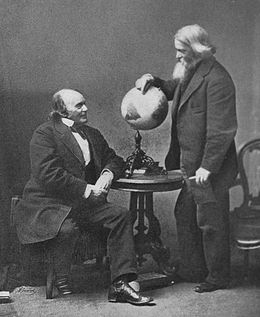

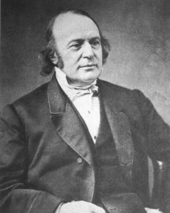

Louis Agassiz

Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (/ˈæɡəsi/ AG-ə-see; French: [aɡasi]) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14, 1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history.

After studying with Georges Cuvier and Alexander von Humboldt in Paris, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel.

He made institutional and scientific contributions to zoology, geology, and related areas, including multivolume research books running to thousands of pages.

Louis Agassiz was born in the village of Môtier (fr) (now part of Haut-Vully which merged into Mont-Vully in 2016) in the Swiss Canton of Fribourg.

His father was a Protestant clergyman, as had been his progenitors for six generations, and his mother was the daughter of a physician and an intellectual in her own right, who had assisted her husband in the education of her boys.

They returned home to Europe with many natural objects, including an important collection of the freshwater fish of Brazil, especially of the Amazon River.

Spix, who died in 1826, likely from a tropical disease, did not live long enough to work out the history of those fish, and Martius selected Agassiz for this project.

[4] In November 1832, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel, at a salary of about US$400 and declined brilliant offers in Paris because of the leisure for private study that that position afforded him.

Trained to scientific drawing by her brothers, his wife was of the greatest assistance to Agassiz, with some of the most beautiful plates in fossil and freshwater fishes being drawn by her.

The fossils that he examined rarely showed any traces of the soft tissues of fish but instead, consisted chiefly of the teeth, scales, and fins, with the bones being perfectly preserved in comparatively few instances.

He therefore adopted a classification that divided fish into four groups (ganoids, placoids, cycloids, and ctenoids), based on the nature of the scales and other dermal appendages.

[4] Before Agassiz's first visit to England in 1834, Hugh Miller and other geologists had brought to light the remarkable fossil fish of the Old Red Sandstone of the northeast of Scotland.

They were of intense interest to Agassiz and formed the subject of a monograph by him published in 1844–1(45: Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Grès Rouge, ou Système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Îles Britanniques et de Russie (Monograph on Fossil Fish of the Old Red Sandstone, or Devonian System of the British Isles and of Russia).

[4] Agassiz visited England, and with William Buckland, the only English naturalist who shared his ideas, made a tour of the British Isles in search of glacial phenomena, and became satisfied that his theory of an ice age was correct.

[13] In it, he discussed the movements of the glaciers, their moraines, and their influence in grooving and rounding the rocks and in producing the striations and roches moutonnées seen in Alpine-style landscapes.

[25] In 1850, he had married Elizabeth Cabot Cary, who later wrote introductory books about natural history and a lengthy biography of her husband after he had died.

[24] Elizabeth wrote at the Strait that "the Hassler pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by them....

[37] In 1863, Agassiz's daughter Ida married Henry Lee Higginson, who later founded the Boston Symphony Orchestra and was a benefactor to Harvard and other schools.

[39] In the last years of his life, Agassiz worked to establish a permanent school in which zoological science could be pursued amid the living subjects of its study.

In 1873, the private philanthropist John Anderson gave Agassiz the island of Penikese, in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts (south of New Bedford), and presented him with $50,000 to endow it permanently as a practical school of natural science that would be especially devoted to the study of marine zoology.

[40] Agassiz had a profound influence on the American branches of his two fields and taught many future scientists who would go on to prominence, including Alpheus Hyatt, David Starr Jordan, Joel Asaph Allen, Joseph Le Conte, Ernest Ingersoll, William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, Nathaniel Shaler, Samuel Hubbard Scudder, Alpheus Packard, and his son Alexander Emanuel Agassiz.

He would allegedly "lock a student up in a room full of turtle-shells, or lobster-shells, or oyster-shells, without a book or a word to help him, and not let him out till he had discovered all the truths which the objects contained.

"[41] Two of Agassiz's most prominent students detailed their personal experiences under his tutelage: Scudder, in a short magazine article for Every Saturday,[42] and Shaler, in his Autobiography.

[57] Agassiz took part in a monthly gathering called the Saturday Club at the Parker House, a meeting of Boston writers and intellectuals.

He was therefore mentioned in a stanza of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. poem "At the Saturday Club:" There, at the table's further end I see In his old place our Poet's vis-à-vis, The great PROFESSOR, strong, broad-shouldered, square, In life's rich noontide, joyous, debonair ...

[63][64] In 2011, Tamara Lanier wrote a letter to the president of Harvard that identified herself as a direct descendant of the Taylors and asked the university to turn over the photos to her.

[70] He made questionable judgment calls such as dismissing Hindu skull calculations from his Caucasian cranial measurements because they brought the overall average down.

[70] Agassiz repeated this lecture 10 months later to the Charleston Literary Club but changed his original stance, claiming that black people were physiologically and anatomically a distinct species.

Stephen Jay Gould asserted that Agassiz's observations sprang from racist bias, in particular from his revulsion on first encountering African-Americans in the United States.

[73] Referencing letters written by Agassiz, Gould compares Agassiz' public display of dispassionate objectivity to his private correspondence, in which he describes "the production of half breeds" as "a sin against nature..." Describing the interbreeding of white and black people, he warns, "We have already had to struggle, in our progress, against the influence of universal equality... but how shall we eradicate the stigma of a lower race when its blood has once been allowed to flow freely into our children."