Adam Mickiewicz

Mickiewicz was born in the Russian-partitioned territories of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which had been part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and was active in the struggle to win independence for his home region.

After, as a consequence, spending five years exiled to central Russia, in 1829 he succeeded in leaving the Russian Empire and, like many of his compatriots, lived out the rest of his life abroad.

[18] By 1820 he had already finished another major romantic poem, Oda do młodości (Ode to Youth), but it was considered to be too patriotic and revolutionary for publication and would not appear officially for many years.

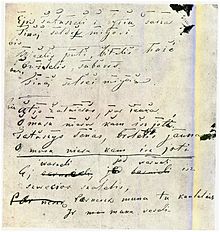

[18] Within a few hours of receiving the decree on 22 October 1824, he penned a poem into an album belonging to Salomea Bécu [pl], the mother of Juliusz Słowacki.

[18][22][23] Mickiewicz was welcomed into the leading literary circles of Saint Petersburg and Moscow, where he became a great favourite for his agreeable manners and an extraordinary talent for poetic improvisation.

[23] Novosiltsev, who recognized its patriotic and subversive message, which had been missed by the Moscow censors, unsuccessfully attempted to sabotage its publication and to damage Mickiewicz's reputation.

[24] On 19 April 1831 Mickiewicz departed Rome, traveling to Geneva and Paris and later, on a false passport, to Germany, via Dresden and Leipzig arriving about 13 August in Poznań (German name: Posen), then part of the Kingdom of Prussia.

[26] On 31 July 1832 he arrived in Paris, accompanied by a close friend and fellow ex-Philomath, the future geologist and Chilean educator Ignacy Domeyko.

[27] His relative literary silence, beginning in the mid-1830s, has been variously interpreted: he may have lost his talent; he may have chosen to focus on teaching and on political writing and organizing.

[34][35] In 1846 Mickiewicz severed his ties with Towiański, following the rise of revolutionary sentiment in Europe, manifested in events such as the Kraków Uprising of February 1846.

[37] In March 1848 he was part of a Polish delegation received in audience by Pope Pius IX, whom he asked to support the enslaved nations and the French Revolution of 1848.

[37] In the winter of 1848–49, Polish composer Frédéric Chopin, in the final months of his own life, visited his ailing compatriot soothed the poet's nerves with his piano music.

[40][41] He returned ill from a trip to a military camp to his apartment on Yenişehir Street in the Pera (now Beyoğlu) district of Constantinople and died on 26 November 1855.

[26] Part III was largely written over a few days; the "Great Improvisation" section, a "masterpiece of Polish poetry", is said to have been created during a single inspired night.

[26] A long descriptive poem, Ustęp (Digression), accompanying part III and written sometime before it, sums up Mickiewicz's experiences in, and views on, Russia, portrays it as a huge prison, pities the oppressed Russian people, and wonders about their future.

[47] Miłosz describes it as a "summation of Polish attitudes towards Russia in the nineteenth century" and notes that it inspired responses from Pushkin (The Bronze Horseman) and Joseph Conrad (Under Western Eyes).

[47] The drama was first staged by Stanisław Wyspiański in 1901, becoming, in Miłosz's words, "a kind of national sacred play, occasionally forbidden by censorship because of its emotional impact upon the audience."

[33][48] Mickiewicz's Konrad Wallenrod (1828), a narrative poem describing battles of the Christian order of Teutonic Knights against the pagans of Lithuania,[15] is a thinly veiled allusion to the long feud between Russia and Poland.

[15][23] The plot involves the use of subterfuge against a stronger enemy, and the poem analyzes moral dilemmas faced by the Polish insurgents who would soon launch the November 1830 Uprising.

[23] Controversial to an older generation of readers, Konrad Wallenrod was seen by the young as a call to arms and was praised as such by an Uprising leader, poet Ludwik Nabielak [pl].

Mickiewicz's Crimean Sonnets (1825–26) and poems that he would later write in Rome and Lausanne, Miłosz notes, have been "justly ranked among the highest achievements in Polish [lyric poetry].

[24] He was an authority to the young insurgents of 1830–31, who expected him to participate in the fighting (the poet Maurycy Gosławski [pl] wrote a dedicated poem urging him to do so).

[24] Yet it is likely that Mickiewicz was no longer as idealistic and supportive of military action as he had been a few years earlier, and his new works such as Do Matki Polki [pl] (To a Polish Mother, 1830), while still patriotic, also began to reflect on the tragedy of resistance.

[27] Pan Tadeusz (Sir Thaddeus, published 1834), another of his masterpieces, is an epic poem that draws a picture of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania on the eve of Napoleon's 1812 invasion of Russia.

[69] Moreover, Mickiewicz's works has influenced the pioneers of the Lithuanian National Revival in the 19th century (e.g. Antanas Baranauskas, Jonas Basanavičius, Stasys Matulaitis, Mykolas Biržiška, Petras Vileišis).

Mickiewicz's importance extends beyond literature to the broader spheres of culture and politics; Wyka writes that he was a "singer and epic poet of the Polish people and a pilgrim for the freedom of nations.

"[41][70][71] On hearing of Mickiewicz's death, his fellow bard Krasiński wrote: For men of my generation, he was milk and honey, gall and life's blood: we all descend from him.

[40][99][100][101] Polish historian Kazimierz Wyka, in his biographic entry in Polski Słownik Biograficzny (1975) wrote that this hypothesis, based on the fact that his mother's maiden name, Majewska, was popular among Frankist Jews, but has not been proven.

[12] Mickiewicz had been brought up in the culture of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a multicultural state that had encompassed most of what today are the separate countries of Poland, Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine.

To Mickiewicz, a splitting of that multicultural state into separate entities – due to trends such as Lithuanian National Revival – was undesirable,[12] if not outright unthinkable.