Lithuanian language

Thus, it is an important source for the reconstruction of the Proto-Indo-European language despite its late attestation (with the earliest texts dating only to c. 1500 AD, whereas Ancient Greek was first written down about three thousand years earlier in c. 1450 BC).

[14][16] There was fascination with the Lithuanian people and their language among the late 19th-century researchers, and the philologist Isaac Taylor wrote the following in his The Origin of the Aryans (1892): "Thus it would seem that the Lithuanians have the best claim to represent the primitive Aryan race, as their language exhibits fewer of those phonetic changes, and of those grammatical losses which are consequent on the acquirement of a foreign speech.

"[17]Lithuanian was studied by several linguists such as Franz Bopp, August Schleicher, Adalbert Bezzenberger, Louis Hjelmslev,[18] Ferdinand de Saussure,[19] Winfred P. Lehmann and Vladimir Toporov,[20] Jan Safarewicz,[21] and others.

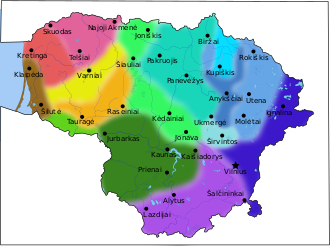

[9] Such eastern boundaries partly coincide with the spread of Catholic and Orthodox faith, and should have existed at the time of the Christianization of Lithuania in 1387 and later.

[9] Safarewicz's eastern boundaries were moved even further to the south and east by other scholars (e.g. Mikalay Biryla [be], Petras Gaučas [lt], Jerzy Ochmański [pl], Aleksandras Vanagas, Zigmas Zinkevičius, and others).

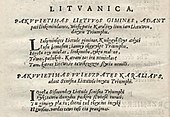

[23][9] It is believed that prayers were translated into the local dialect of Lithuanian by Franciscan monks during the baptism of Mindaugas, however none of the writings has survived.

[36] Soon afterwards Vytautas the Great wrote in his 11 March 1420 letter to Sigismund, Holy Roman Emperor, that Lithuanian and Samogitian are the same language.

[34] For example, since the young Grand Duke Casimir IV Jagiellon was underage, the supreme control over the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was in the hands of the Lithuanian Council of Lords, presided by Jonas Goštautas, while Casimir IV Jagiellon was taught Lithuanian and customs of Lithuania by appointed court officials.

[23] At the royal courts in Vilnius of Sigismund II Augustus, the last Grand Duke of Lithuania prior to the Union of Lublin, both Polish and Lithuanian were spoken equally widely.

[50][51] In the 16th century, following the decline of Ruthenian usage in favor of Polish in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, the Lithuanian language strengthened its positions in Lithuania due to reforms in religious matters and judicial reforms which allowed lower levels of the Lithuanian nobility to participate in the social-political life of the state.

[28] In 1599, Mikalojus Daukša published his Postil and in its prefaces he expressed that the Lithuanian language situation had improved and thanked bishop Merkelis Giedraitis for his works.

[58][59][60][61][62] In 1864, following the January Uprising, Mikhail Muravyov, the Russian Governor General of Lithuania, banned the language in education and publishing and barred use of the Latin alphabet altogether, although books continued to be printed in Lithuanian across the border in East Prussia and in the United States.

[63][64] Brought into the country by book smugglers (Lithuanian: knygnešiai) despite the threat of long prison sentences, they helped fuel growing nationalist sentiment that finally led to the lifting of the ban in 1904.

[73] The conventions of written Lithuanian had been evolving during the 19th century, but Jablonskis, in the introduction to his Lietuviškos kalbos gramatika, was the first to formulate and expound the essential principles that were so indispensable to its later development.

[74] The Baltic-origin place names retained their basis for centuries in Prussia but were Germanized (e.g. Tilžė – Tilsit, Labguva – Labiau, Vėluva – Wehliau, etc.

); however, after the annexation of the Königsberg region into the Russian SFSR, they were changed completely, regardless of previous tradition (e.g. Tilsit – Sovetsk, Labiau – Polesk, Wehliau – Znamensk, etc.).

[74] Soviet authorities introduced Lithuanian–Russian bilingualism,[74] and Russian, as the de facto official language of the USSR, took precedence and the use of Lithuanian was reduced in a process of Russification.

[88] He proposed that the two language groups were indeed a unity after the division of Indo-European, but also suggested that after the two had divided into separate entities (Baltic and Slavic), they had posterior contact.

However, as for the hypotheses related to the "Balto-Slavic problem", it is noted that they are more focused on personal theoretical constructions and deviate to some extent from the comparative method.

It is also spoken by ethnic Lithuanians living in today's Belarus, Latvia, Poland, and the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia, as well as by sizable emigrant communities in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, Uruguay, and Spain.

[74][23] The other two regional variants of the common language were formed in Lithuania proper: middle, which was based on the specifics of the Duchy of Samogitia (e.g. works of Mikalojus Daukša, Merkelis Petkevičius, Steponas Jaugelis‑Telega, Samuelis Boguslavas Chylinskis, and Mikołaj Rej's Lithuanian postil), and eastern, based on the specifics of Eastern Aukštaitians, living in Vilnius and its region (e.g. works of Konstantinas Sirvydas, Jonas Jaknavičius, and Robert Bellarmine's catechism).

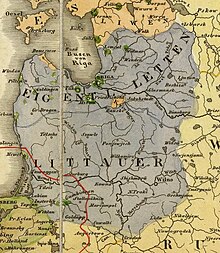

[52] Since the 19th century to 1925 the amount of Lithuanian speakers in Lithuania Minor (excluding Klaipėda Region) decreased from 139,000 to 8,000 due to Germanisation and colonization.

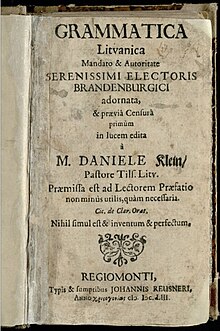

[123] In the Grammatica Litvanica Klein also established the letter W for marking the sound [v], the use of which was later abolished in Lithuanian (it was replaced with V, notably by authors of the Varpas newspaper).

There are a few exceptions: for example, the letter i represents either the vowel [ɪ], as in English sit, or is silent and merely indicates that the preceding consonant is palatalized.

[128][123] A macron (on u), an ogonek (on a, e, i, and u), a dot (on e), and y (in place of i) are used for grammatical and historical reasons and always denote vowel length in Modern Standard Lithuanian.

However, these pitch accents are generally not written, except in dictionaries, grammars, and where needed for clarity, such as to differentiate homonyms and dialectal use.

Lithuanian verbal morphology shows a number of innovations; namely, the loss of synthetic passive (which is hypothesized based on other archaic Indo-European languages, such as Greek and Latin), synthetic perfect (formed by means of reduplication) and aorist; forming subjunctive and imperative with the use of suffixes plus flexions as opposed to solely flections in, e.g., Ancient Greek; loss of the optative mood; merging and disappearing of the -t- and -nt- markers for the third-person singular and plural, respectively (this, however, occurs in Latvian and Old Prussian as well and may indicate a collective feature of all Baltic languages).

On the other hand, Lithuanian verbal morphology retains a number of archaic features absent from most modern Indo-European languages (but shared with Latvian).

In practical terms, the rich overall inflectional system makes the word order have a different meaning than in more analytic languages such as English.

The majority of the loanwords were found to have been derived from Polish, Belarusian, and German, with some evidence that these languages all acquired the words from contacts and trade with Prussia during the era of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.