Adams v. Tanner

Washington voters passed a ballot initiative, supported by the then Federal Department of Labor, to prohibit private employment agencies charging fees to people seeking work.

Mr Justice Reynold said, there is nothing inherently immoral or dangerous to public welfare in acting as paid representative of another to find a position in which he can earn an honest living.

He highlighted sources from US Labor Department giving examples of abuse, attempts in over thirty states to regulate and have free public agencies compete.

Sometimes, agencies made no effort to place the worker, or the work would last a few days and the employer would then split the next fee with the agent to bring in fresh replacements.

Plaintiffs, who are proprietors of private employment agencies in the City of Spokane, assert that this statute, if enforced, would compel them to discontinue business, and would thus, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, deprive them of their liberty and property without due process of law.

[1] But even if it should prove, as plaintiffs allege, that their business could not live without collecting fees from employees, that fact would not necessarily render the act invalid.

And this Court has made it clear that a statute enacted to promote health, safety, morals, or the public welfare may be valid, although it will compel discontinuance of existing businesses in whole or in part.

"If the state thinks that an admitted evil cannot be prevented except by prohibiting a calling or transaction not in itself necessarily objectionable, the courts cannot interfere unless, in looking at the substance of the matter, they can see that it 'is a clear, unmistakable infringement of rights secured by the fundamental law.'"

Or, as it is so frequently expressed, the action of the legislature is final unless the measure adopted appears clearly to be arbitrary or unreasonable, or to have no real or substantial relation to the object sought to be attained.

The sole purpose of the inquiries is to enable this Court to decide whether, in view of the facts, actual or possible, the action of the State of Washington was so clearly arbitrary or so unreasonable that it could not be taken "by a free government without a violation of fundamental rights."

And it is true also that many applicants perpetrate frauds on the labor agents themselves – as, for example, causing them to return fees when positions actually were secured.

The fees which private employment offices must charge are barriers which prevent the proper flow of labor into the channels where it is needed, and are a direct influence in keeping men idle.

An additional injustice inevitably connected with labor agencies which charge fees is that they must place the entire cost of the service upon those least able to bear it.

The weakest and poorest classes of wage earners are therefore made to pay the largest share for a service rendered to employers, to workers, and to the public as well."

There gradually developed a conviction that the evils of private agencies were inherent and ineradicable so long as they were permitted to charge fees to the workers seeking employment.

Where the states and cities have spent much money for inspectors and complaint adjusters, there has been considerable improvement in the methods of private employment agencies, but most of the officers in charge of this regulation testify that the abuses are in 'the nature of the business,' and never can be entirely eliminated.

The conviction became widespread that, for the solution of the larger problem of unemployment, the aid of the federal government and the utilization and development of its extensive machinery was indispensable.

These were declared by Congress to be: "to foster, promote and develop the welfare of the wage earners of the United States, to improve their working conditions, and to advance their opportunities for profitable employment."

In the summer of 1914, and in part before the filing in the State of Washington of the proposal for legislation here in question, action had been taken by the Department of Labor which attracted public attention.

As early as June 13, 1914, the United States Department of Labor had also sought the cooperation in this work of all the leading newspapers in America, including those printed in foreign languages.

"The necessity laid upon so many workers of constantly seeking new jobs opens a peculiarly fertile field for their exploitation by unscrupulous private employment agencies.

The most striking evidence of this is that, in the State of Washington, private agencies made themselves so generally distrusted that, in 1915, their complete abolition was ordered by popular vote...

The reports of the Washington State Bureau of Labor give this description: "The investigations of the Bureau show that the worst labor conditions in the state are to be found on highway and railroad construction work, and these are largely because the men are sent long distances by the employment agencies, are housed and fed poorly at the camps, and are paid on an average of $1.75 to $2.25 a day, out of which they are compelled to pay $5.50 to $7 per week for board, generally a hospital fee of some kind, always a fee to the employment agency, and their transportation to the point where the work is being done.

[12]" "That the honest toiler was their victim there is no question: not alone of a stiff fee for the information given, but a systematic method was adopted in order to keep the business going.

Men in large numbers would be sent to contract jobs, and if on the railroads, 'free fare' was part of the inducement, or perhaps the agency would charge a nominal fee if the distance was great, and this, too, would become a perquisite of the bureau, to finally go through the clearing house.

[20] In the State of Washington, the suffering from unemployment was accentuated by the lack of staple industries operating continuously throughout the year and by unusual fluctuations in the demand for labor, with consequent reduction of wages and increase of social unrest.

[21] Students of the larger problem of unemployment appear to agree that establishment of an adequate system of employment offices or labor exchanges[22] is an indispensable first step toward its solution.

1 called for each member to, take measures to prohibit the establishment of employment agencies which charge fees or which carry on their business for profit.

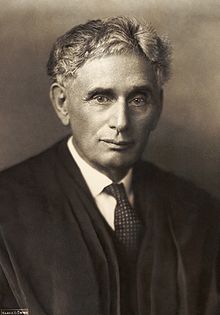

In Ribnik v. McBride, 277 U.S. 350 (1928), the Court struck down a similar New Jersey law attempting to regulate agencies, Justices Stone, Brandeis and Holmes dissenting.

In the latter, Mr Justice Black said that Adams v. Tanner was part of the "constitutional philosophy" that struck down minimum wages and maximum working hours.