Adelaide leak

During the course of play on 14 January 1933, the Australian Test captain Bill Woodfull was struck over the heart by a ball delivered by Harold Larwood.

On his return to the Australian dressing room, Woodfull was visited by the managers of the Marylebone Cricket Club (MCC) team, Pelham Warner and Richard Palairet.

Fingleton later wrote that Donald Bradman, Australia's star batsman and the primary target of Bodyline, was the person who disclosed the story.

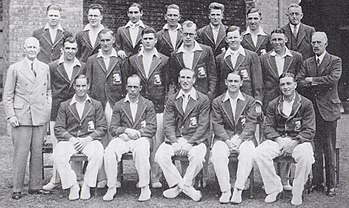

In 1932–33 the English team, led by Douglas Jardine and jointly managed by Pelham Warner and Richard Palairet, toured Australia and won the Ashes in an acrimonious contest that became known as the Bodyline series.

The deliveries were often short-pitched, designed to rise at the batsman's body, with four or five fielders close by on the leg side waiting to catch deflections off the bat.

In one match, he bowled short at Jack Hobbs; in his capacity as cricket correspondent of The Morning Post, Warner was highly critical of the Yorkshire bowlers and Bowes in particular.

[7] In Australia, while Jardine's unfriendly approach and superior manner caused some friction with the press and spectators, the early tour matches were uncontroversial and Larwood and Voce had a light workload in preparation for the Test series.

He was accused of hypocrisy for not taking a stand on either side,[15] particularly after expressing sentiments at the start of the tour that cricket "has become a synonym for all that is true and honest.

"[16] Jardine's tactics were successful in one respect: in six innings against the tourists ahead of the Tests, Bradman scored only 103 runs, causing concern among the Australian public who expected much more from him.

[21] Later hostility arose from Bradman's public preference for Bill Brown as a batsman, which Fingleton believed cost him a place on the 1934 tour of England.

[29] Critics began to believe Bodyline was not quite the threat that had been perceived and Bradman's reputation, which had suffered slightly with his earlier failures, was restored.

[32][33] During the mid-afternoon of Saturday 14 January 1933, the second day of the Third Test, Woodfull and Fingleton opened the batting for Australia in the face of an England total of 341 before a record attendance of 50,962 people.

[36][37] Play resumed after a brief delay, once it was certain the Australian captain was fit to carry on, and since Larwood's over had ended, Woodfull did not have to face the bowling of Allen in the next over.

However, when Larwood was ready to bowl at Woodfull again, play was halted once more when the fielders were moved into Bodyline positions, causing the crowd to protest and call abuse at the England team.

[39] Jardine, although writing that Woodfull could have retired hurt if he was unfit, later expressed his regret at making the field change at that moment.

It is likely Jardine wished to press home his team's advantage in the match, and the Bodyline field was usually employed at this stage of an innings.

When a doctor was publicly requested, to attend an injury to Voce, many in the crowd believed it was Woodfull who required assistance, leading to a renewal of protest.

[41] Later in the afternoon, while Ponsford and Richardson were still batting, Warner and Palairet visited the Australian dressing room with the intention of enquiring about Woodfull's health.

[42] According to the original newspaper reports and Fingleton's later description, Woodfull was lying on the masseur's table, awaiting treatment from a doctor, although this may have been an exaggeration for dramatic effect.

[47] The England captain then locked the dressing room doors and told the team what Woodfull had said and warned them not to speak to anyone concerning the matter.

He wrote in the Telegraph that the "fires which have been smouldering in the ranks of the Australian Test cricketers regarding the English shock attack suddenly burst into flames yesterday.

David Frith notes that discretion and respect were highly prized and such a leak was "regarded as a moral offence of the first order.

"[51][52] As the only full-time journalist in the Australian team, suspicion immediately fell on Fingleton, although as soon as the story was published, he told Woodfull he was not responsible.

[54] Woodfull denied through Bill Jeanes, the Secretary of the Australian Board of Control, that he had expressed regret, but he had said there was no personal animosity between the two men.

[67][68] During the play on Monday, a short ball from Larwood fractured Bert Oldfield's skull, although Bodyline tactics were not being used at the time.

[69] The Australian Board of Control contacted the MCC managers Warner and Palairet asking them to arrange for the team to cease the use of Bodyline, but they replied the captain was solely in charge of the playing side of the tour.

[72] Jardine threatened to withdraw his team from the Fourth and Fifth Tests unless the Australian Board retracted the accusation of unsporting behaviour.

[73] The MCC responded angrily to the accusations of unsporting conduct, played down the Australian claims about the danger of Bodyline and threatened to call off the tour.

The series had become a major diplomatic incident by this stage, and many people saw Bodyline as damaging to an international relationship that needed to remain strong.

Alexander Hore-Ruthven, the Governor of South Australia, who was in England at the time, expressed his concern to J. H. Thomas, the British Secretary of State for Dominion Affairs that this would cause a significant impact on trade between the nations.