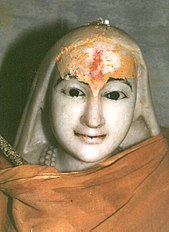

Adi Shankara

[1] Reliable information on Shankara's actual life is scanty,[2] and his true impact lies in his "iconic representation of Hindu religion and culture," despite the fact that most Hindus do not adhere to Advaita Vedanta.

[14] Hagiographies dating from the 14th-17th centuries deified him as a ruler-renunciate, travelling on a digvijaya (conquest of the four quarters)[15][16] across the Indian subcontinent to propagate his philosophy, defeating his opponents in theological debates.

[17][18] These hagiographies portray him as founding four mathas ("monasteries"), and Adi Shankara also came to be regarded as the organiser of the Dashanami monastic order, and the unifier of the Shanmata tradition of worship.

[7][9] Maṇḍana Miśra, an older contemporary of Shankara,[6] was a Mimamsa scholar and a follower of Kumarila, but also wrote a seminal text on Advaita that has survived into the modern era, the Brahma-siddhi.

[73] It was only after Shankara that "the theologians of the various sects of Hinduism utilized Vedanta philosophy to a greater or lesser degree to form the basis of their doctrines,"[74] whereby "its theoretical influence upon the whole of Indian society became final and definitive.

[75] In medieval times, Advaita Vedanta position as most influential Hindu darsana started to take shape, as Advaitins in the Vijayanagara Empire competed for patronage from the royal court, and tried to convert others to their sect.

This may have been in response to the devastation caused by the Islamic Delhi Sultanate,[11][13][77][79] but his efforts were also targeted at Sri Vaishnava groups, especially Visishtadvaita, which was dominant in territories conquered by the Vijayanagara Empire.

[76] Vidyaranya and his brothers, note Paul Hacker and other scholars,[11][13] wrote extensive Advaitic commentaries on the Vedas and Dharma to make "the authoritative literature of the Aryan religion" more accessible.

[81] Vidyaranya was an influential Advaitin, and he created legends to turn Shankara, whose elevated philosophy had no appeal to gain widespread popularity, into a "divine folk-hero who spread his teaching through his digvijaya ("universal conquest," see below) all over India like a victorious conqueror.

[39] Most also mention a meeting with scholars of the Mimamsa school of Hinduism namely Kumarila and Prabhakara, as well as Mandana and various Buddhists, in Shastrartha (an Indian tradition of public philosophical debates attended by large number of people, sometimes with royalty).

Different and widely inconsistent accounts of his life include diverse journeys, pilgrimages, public debates, installation of yantras and lingas, as well as the founding of monastic centers in north, east, west and south India.

[2][94] While the details and chronology vary, most hagiographies present Shankara as traveling widely within India, Gujarat to Bengal, and participating in public philosophical debates with different orthodox schools of Hindu philosophy, as well as heterodox traditions such as Buddhists, Jains, Arhatas, Saugatas, and Charvakas.

[96] Ten monastic orders in different parts of India are generally attributed to Shankara's travel-inspired Sannyasin schools, each with Advaita notions, of which four have continued in his tradition: Bharati (Sringeri), Sarasvati (Kanchi), Tirtha and Asramin (Dvaraka).

[99] Other monasteries that record Shankara's visit include Giri, Puri, Vana, Aranya, Parvata and Sagara – all names traceable to Ashrama system in Hinduism and Vedic literature.

[96][100] According to hagiographies, supported by four maths, Adi Shankara died at Kedarnath in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand, a Hindu pilgrimage site in the Himalayas.

From the 14th century onwards hagiographies were composed, in which he is portrayed as establishing the Daśanāmi Sampradaya,[104] organizing a section of the Ekadandi monks under an umbrella grouping of ten names.

[105][106] According to tradition, Adi Sankara organised the Hindu monks of these ten sects or names under four Maṭhas (Sanskrit: मठ) (monasteries), with the headquarters at Dvārakā in the West, Jagannatha Puri in the East, Sringeri in the South and Badrikashrama in the North.

[note 17] Shankara's position was further established in the 19th and 20th-century, when neo-Vedantins and western Orientalists elevated Advaita Vedanta "as the connecting theological thread that united Hinduism into a single religious tradition.

[120][121]Adi Shankara is highly esteemed in contemporary Advaita Vedanta, and over 300 texts are attributed to his name, including commentaries (Bhāṣya), original philosophical expositions (Prakaraṇa grantha) and poetry (Stotra).

Paul Hacker has also expressed some reservations that the compendium Sarva-darsana-siddhanta Sangraha was completely authored by Shankara, because of difference in style and thematic inconsistencies in parts.

[139][note 21] Benedict Ashley credits Adi Shankara for unifying two seemingly disparate philosophical doctrines in Hinduism, namely Atman and Brahman.

Shankara's primary objective was to explain how moksha is attained in this life by recognizing the true identity of jivatman as Atman-Brahman,[25] as mediated by the Mahāvākyas, especially Tat Tvam Asi, "That you are."

[citation needed] According to Sengaku Mayeda, "in no place in his works [...] does he give any systematic account of them,"[165] taking Atman-Brahman to be self-evident (svapramanaka) and self-established (svatahsiddha), and "an investigation of the means of knowledge is of no use for the attainment of final release.

"[165] Mayeda notes that Shankara's arguments are "strikingly realistic and not idealistic," arguing that jnana is based on existing things (vastutantra), and "not upon Vedic injunction (codanatantra) nor upon man (purusatantra).

[32][note 28] Sircar in 1933 offered a different perspective and stated, "Sankara recognizes the value of the law of contrariety and self-alienation from the standpoint of idealistic logic; and it has consequently been possible for him to integrate appearance with reality.

"[171] Recent scholarship states that Shankara's arguments on revelation are about apta vacana (Sanskrit: आप्तवचन, sayings of the wise, relying on word, testimony of past or present reliable experts).

[180] Describing Shankara's style of yogic practice, Comans writes: the type of yoga which Sankara presents here is a method of merging, as it were, the particular (visesa) into the general (samanya).

[180] Shankara cautioned against cherrypicking a phrase or verse out of context from Vedic literature, and remarks in the opening chapter of his Brahmasutra-Bhasya that the Anvaya (theme or purport) of any treatise can only be correctly understood if one attends to the Samanvayat Tatparya Linga, that is six characteristics of the text under consideration: (1) the common in Upakrama (introductory statement) and Upasamhara (conclusions); (2) Abhyasa (message repeated); (3) Apurvata (unique proposition or novelty); (4) Phala (fruit or result derived); (5) Arthavada (explained meaning, praised point) and (6) Yukti (verifiable reasoning).

[194][204][206] "Tvam" refers to one's real I, pratyagatman or inner Self,[208] the "direct Witness within everything,"[209] "free from caste, family, and purifying ceremonies,"[210] the essence, Atman, which the individual at the core is.

[246] The non-Advaita scholar Bhaskara of the Bhedabheda Vedānta tradition, similarly around 800 CE, accused Shankara's Advaita as "this despicable broken down Mayavada that has been chanted by the Mahayana Buddhists", and a school that is undermining the ritual duties set in Vedic orthodoxy.