Adolf Spiess

It was therefore natural that one feature of the daily program should be gymnastics, as described and practised by GutsMuths — walking the balance beam, jumping, running, climbing, throwing, skating, swimming, etc., and games of all sorts.

He went on many mountain and castle excursions with friends, and displayed skill in all forms of physical activity — riding, swimming, skating, dancing, and gymnastics.

He modified the traditional method by gathering the entire number into one band at the commencement of each period for various simple exercises performed in rhythm as they stood or marched, or for running and jumping under the leadership of a single teacher.

The Hessian authorities were on the lookout for agitation looking toward a united Germany, and had already given notice to the University that no student who was affiliated with forbidden organizations, like the Burschenschaft, would be admitted to the regular examinations.

Around this time, on a visit to his family in Sprendlingen, one evening a friendly magistrate informed his father that if Adolf was found in the house on the following morning he would be subject to arrest.

The clergyman, recognizing that a sojourn in a neutral country was the only safe course for his son, in view of existing political conditions, at once wrote to propose Adolf for the place.

The city authorities had erected a new, attractive, and roomy building for the school, and now placed at its head Friedrich Fröbel, already widely known for his book The Education of Man (1826).

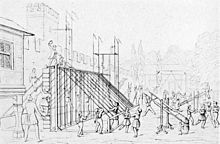

The open-air gymnasium, originally laid out after the Jahn plan in 1824, and beautifully situated in a grove near the left bank of the Emme, overlooked to the east by wooded sandstone cliffs beyond the stream and on the west by an ancient castle, was now doubled in size and entirely refitted in accordance with the wishes of the new teacher.

In the spring of 1834 the boys of the school, including even the youngest, began to receive systematic instruction in gymnastics for two successive hours on three afternoons of each week, and before long the interest of the girls, also, was awakened and special classes were formed and suitable exercises devised to meet their needs.

They were intended to secure ready control and graceful carriage of the body under ordinary conditions, while the pupil was standing or walking on the usual supporting surface, and differed in this particular from the forms commonly practised on the old Turnplatz.

The next step was a review of all the gymnastic material in the effort to devise a more satisfactory classification than the one adopted in the books of GutsMuths, Jahn's Deutsche Turnkunst, and Eiselen's Turntafeln (1837).

In the summer of 1842 Spiess returned to Germany, drawn by the signs of approaching gymnastic revival in Prussia and the desire to discuss his own views with other men of like interests.

On the request of Eichhorn, once back in Burgdorf, Spiess followed up the visit on 18 October with a formal statement of his ideas regarding the essential features of a state system of physical training for the schools, "Thoughts on the method to be followed in making gymnastics an integral element in popular education."

Two years earlier, Spiess had married a former pupil, Marie Buri, and the need of finding a larger and more remunerative field of usefulness no doubt had much to do with the journey to Berlin; but the summons of Massmann to the Prussian capital in 1843 put an end to all hopes in that direction.

With further attempts, he received a call from Basel to the position of teacher of gymnastics and history in two higher schools for boys — the Gymnasium and the Realschule — and at the orphan asylum.

Free at last to devote all his thought to the one subject, he finished in 1846 the fourth and final part of his System of Gymnastics, and the next year was able to publish the first volume of a practical manual for teachers (Turnbuch für Schulen), containing graded series of exercises suitable for boys and girls between the ages of six and ten.

A four weeks' normal course was given in 1849 to about 30 teachers in elementary and higher schools, most of them from Darmstadt, but one from Dresden and ten from Mainz, Offenbach, Worms, and other Hessian towns.