Aerial warfare during Operation Barbarossa

With its factories in the Urals, out of range from Axis medium bombers, Soviet production increased, out-stripping its enemies and enabling the country to replace its aerial losses.

In the following years, Soviet air power recovered from the purges and losses, gradually gaining in tactical and operational competence while closing the technical gap.

The German plan for the USSR was to win a quick war, before Soviet superiority in numbers and industry could take effect, and before the Red Army officer corps (decimated by Joseph Stalin's Great Purge in the 1930s) could recover.

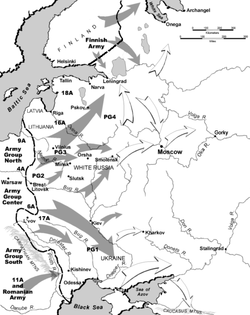

[10] Barbarossa's task was to destroy as much of the Soviet military forces as possible, west of the Dnieper River in Ukraine, in a series of encirclement operations, to prevent a Red Army retreat into the more eastern areas of Russia.

[17] The Luftwaffe thus began preparations to neutralize the Military Aviation of the Workers' and Peasants Red Army (Russian: Voyenno-Vozdushnyye Sily Raboche-Krestyanskaya Krasnaya Armiya, VVS-RKKA often abbreviated to VVS).

Schmid still felt the Luftwaffe could defeat Britain by attacking its industries, while Waldau argued that dissipating German air strength along a wide 'air front' was deeply irresponsible.

[4][30][31] The planning for Barbarossa went ahead, regardless of these failures, and the knowledge that experience in Western Europe had shown that while highly effective, close support operations were costly, and reserves needed to be created to replace losses.

Depending on railroad repair teams to mend the Soviet rail system, they believed they could finish the campaign after reaching Smolensk, using it as a jumping off point to capture Moscow.

[52] Before the Axis invasion of the USSR, Joseph "Beppo" Schmid, the Luftwaffe's senior intelligence officer, identified 7,300 aircraft in the VVS and long-range aviation in the western Soviet Union, when the actual figure was 7,850.

Heinrich Aschenbrenner, the German air attache in Moscow was one of the few in the Nazi regime able to gain any clear insight into Soviet armaments potential, as a result of a visit to six aircraft plants in the Urals in the spring of 1941.

It was believed that Soviet ground attack aviation would be attached to and support the Army Fronts and strategic bomber and fighter forces would held back for air defence.

Even the usually sound and objective Major General Hoffmann von Waldau, chief of the operations staff commented on the Soviets as a "state of most centralised executive power and below-average intelligence".

[72] The Luftwaffe's general picture of the VVS was entirely correct in many aspects in the military field; this was later confirmed in the early stages of Barbarossa and in post-war British and American studies, and also in the Eastern Bloc.

Shortly before the invasion, German engineers were given a guided tour of Soviet industrial complexes and aircraft factories in the Urals from 7 to 16 April, and evidence of extensive production was already underway.

[77] In particular, Aschenbrenner listed some warnings that German intelligence had not picked up: The consolidated report of the visit stressed among than other things: (1) that the factories were completely independent of subsidiary part deliveries (2) the excellently arranged work --- extending down to details [production methods], (3) the well maintained modern machinery, and (4) the technical manual aptitude, devotion frugality of Soviet workers.

[2] Commanded by Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, its main goal was the disruption of Soviet road and rail traffic to and from Leningrad – Murmansk, and the interdiction of shipping in the later port, which was bringing in American equipment across the Atlantic Ocean.

Fedor Kuznetsov, commander of the North-Western Front (Baltic Military District) ordered the large 3rd, 12th and 23rd Mechanised Corps to counterattack the advance of Army Group North.

[98] His commanding officer, Kesselring, ordered Luftflotte 2 to fly armed reconnaissance missions, using bombers and Henschel Hs 123s from LG 2, to suppress the Soviet ground forces being encircled by the Second and Third Panzer Armies.

The Red Army eased German operations by failing to utilise radios and relying on telephone lines, which had been damaged by air attacks, causing communicative chaos.

[99] On a more positive note, the VVS' 4th Attack Aviation Regiment saw action in June; it was equipped with the Ilyushin Il-2 Shturmovik, and although only trained to land and take off in them, their crews were thrown into the fight.

Despite the lack of close support aircraft, which was eased with the arrival of 40 Bf 110s from ZG 26, Luftflotte 1 delivered a series of air attacks, which accounted for around 250 Soviet tanks.

The Soviets had cleverly concentrated their air power at Yelnya, and the mixture of a decline in Luftwaffe strength (to 600 in the central sector) compelled the Germans to withdraw from the salient.

[126] The increased size of the operational theatre, and the ability of the Soviets to replace losses (partly through American Lend-Lease) affected the Luftwaffe's influence on the ground battle.

Soviet production replaced aircraft at an "astonishing" rate, while damage to rail and communication lines were repaired very quickly, meaning German air attacks in this regard could only have temporary effect.

Yet by 30 August, the VVS had sustained air superiority, though it failed to help Zhukov make any head way at Yelnya, and Guderian achieving a series of tactical success at Roslavl and Krichev.

The XXXXI Panzerkorps succeeded in encircling the Soviets, but in their defence the PVO 7 Fighter Aviation Corps engaged Fliegerkorps VIII in a series of intense air battles on 25 August.

It flew 1,313 sorties against Saaremaa island, claiming 26 batteries, 25 artillery pieces, 26 motor vehicles, 16 field emplacements, seven bunkers, seven barracks, one ammunition dump and two columns of horse-drawn transport.

With the VVS needing to concentrate its diminished assets at the critical points, Soviet units were ordered back to Kiev to rebuild and help prevent the Germans crossing the Dniepr.

As Guderian reached the Seym river, halfway between Kiev and Kursk, JG 3 and the Slovak 12 Letka, under the command of Ivan Haluznicky, were concentrated in order to protect them, and were involved in intense air battles with the 249th Fighter Aviation Regiment.

LG 1's Ju 87s could not be concentrated on the force, as they were shifted 320 kilometres to the south to help the Finnish-German XXXVI Corps push to Salla in a bid to isolate the Kola, a plan named Operation Silver Fox.