Affine space

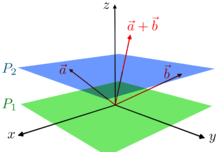

In mathematics, an affine space is a geometric structure that generalizes some of the properties of Euclidean spaces in such a way that these are independent of the concepts of distance and measure of angles, keeping only the properties related to parallelism and ratio of lengths for parallel line segments.

These coefficients define a barycentric coordinate system for the flat through the points.

In finite dimensions, such an affine subspace is the solution set of an inhomogeneous linear system.

Linear subspaces, in contrast, always contain the origin of the vector space.

However, if the sum of the coefficients in a linear combination is 1, then Alice and Bob will arrive at the same answer.

If Alice travels to then Bob can similarly travel to Under this condition, for all coefficients λ + (1 − λ) = 1, Alice and Bob describe the same point with the same linear combination, despite using different origins.

Explicitly, the definition above means that the action is a mapping, generally denoted as an addition, that has the following properties.

The properties of the group action allows for the definition of subtraction for any given ordered pair (b, a) of points in A, producing a vector of

In this case, the addition of a vector to a point is defined from the first of Weyl's axioms.

, one has Therefore, since for any given b in A, b = a + v for a unique v, f is completely defined by its value on a single point and the associated linear map

Another important family of examples are the linear maps centred at an origin: given a point

This affine space is sometimes denoted (V, V) for emphasizing the double role of the elements of V. When considered as a point, the zero vector is commonly denoted o (or O, when upper-case letters are used for points) and called the origin.

) the choice of any point a in A defines a unique affine isomorphism, which is the identity of V and maps a to o.

The inner product of two vectors x and y is the value of the symmetric bilinear form The usual Euclidean distance between two points A and B is In older definition of Euclidean spaces through synthetic geometry, vectors are defined as equivalence classes of ordered pairs of points under equipollence (the pairs (A, B) and (C, D) are equipollent if the points A, B, D, C (in this order) form a parallelogram).

For any two points o and o' one has Thus, this sum is independent of the choice of the origin, and the resulting vector may be denoted When

There are two strongly related kinds of coordinate systems that may be defined on affine spaces.

, the point x is thus the barycenter of the xi, and this explains the origin of the term barycentric coordinates.

For affine spaces of infinite dimension, the same definition applies, using only finite sums.

Example: In Euclidean geometry, Cartesian coordinates are affine coordinates relative to an orthonormal frame, that is an affine frame (o, v1, ..., vn) such that (v1, ..., vn) is an orthonormal basis.

However, in the situations where the important points of the studied problem are affinely independent, barycentric coordinates may lead to simpler computation, as in the following example.

The vertices of a non-flat triangle form an affine basis of the Euclidean plane.

An important example is the projection parallel to some direction onto an affine subspace.

This results from the fact that "belonging to the same fiber of an affine homomorphism" is an equivalence relation.

They can also be studied as synthetic geometry by writing down axioms, though this approach is much less common.

Coxeter (1969, p. 192) axiomatizes the special case of affine geometry over the reals as ordered geometry together with an affine form of Desargues's theorem and an axiom stating that in a plane there is at most one line through a given point not meeting a given line.

(Cameron 1991, chapter 3) gives axioms for higher-dimensional affine spaces.

, and introduce affine algebraic varieties as the common zeros of polynomial functions over kn.

The case of an algebraically closed ground field is especially important in algebraic geometry, because, in this case, the homeomorphism above is a map between the affine space and the set of all maximal ideals of the ring of functions (this is Hilbert's Nullstellensatz).

This is the starting idea of scheme theory of Grothendieck, which consists, for studying algebraic varieties, of considering as "points", not only the points of the affine space, but also all the prime ideals of the spectrum.

More generally, the Quillen–Suslin theorem implies that every algebraic vector bundle over an affine space is trivial.