Manifold

The concept of a manifold is central to many parts of geometry and modern mathematical physics because it allows complicated structures to be described in terms of well-understood topological properties of simpler spaces.

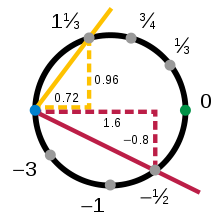

Considering, for instance, the top part of the unit circle, x2 + y2 = 1, where the y-coordinate is positive (indicated by the yellow arc in Figure 1).

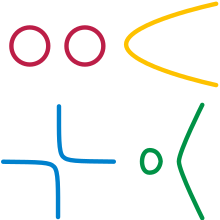

A manifold can be constructed by giving a collection of coordinate charts, that is, a covering by open sets with homeomorphisms to a Euclidean space, and patching functions[clarification needed]: homeomorphisms from one region of Euclidean space to another region if they correspond to the same part of the manifold in two different coordinate charts.

It focuses on an atlas, as the patches naturally provide charts, and since there is no exterior space involved it leads to an intrinsic view of the manifold.

Among the possible quotient spaces that are not necessarily manifolds, orbifolds and CW complexes are considered to be relatively well-behaved.

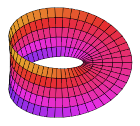

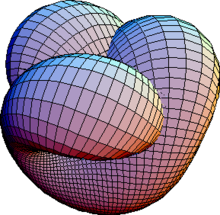

Manifolds which can be constructed by identifying points include tori and real projective spaces (starting with a plane and a sphere, respectively).

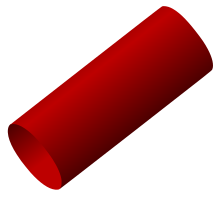

A finite cylinder may be constructed as a manifold by starting with a strip [0,1] × [0,1] and gluing a pair of opposite edges on the boundary by a suitable diffeomorphism.

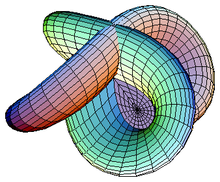

A projective plane may be obtained by gluing a sphere with a hole in it to a Möbius strip along their respective circular boundaries.

The study of manifolds combines many important areas of mathematics: it generalizes concepts such as curves and surfaces as well as ideas from linear algebra and topology.

Leonhard Euler showed that for a convex polytope in the three-dimensional Euclidean space with V vertices (or corners), E edges, and F faces,

On the other hand, a torus can be sliced open by its 'parallel' and 'meridian' circles, creating a map with V = 1 vertex, E = 2 edges, and F = 1 face.

Investigations of Niels Henrik Abel and Carl Gustav Jacobi on inversion of elliptic integrals in the first half of 19th century led them to consider special types of complex manifolds, now known as Jacobians.

Bernhard Riemann further contributed to their theory, clarifying the geometric meaning of the process of analytic continuation of functions of complex variables.

Another important source of manifolds in 19th century mathematics was analytical mechanics, as developed by Siméon Poisson, Jacobi, and William Rowan Hamilton.

This space is, in fact, a high-dimensional manifold, whose dimension corresponds to the degrees of freedom of the system and where the points are specified by their generalized coordinates.

For an unconstrained movement of free particles the manifold is equivalent to the Euclidean space, but various conservation laws constrain it to more complicated formations, e.g. Liouville tori.

The theory of a rotating solid body, developed in the 18th century by Leonhard Euler and Joseph-Louis Lagrange, gives another example where the manifold is nontrivial.

As continuous examples, Riemann refers to not only colors and the locations of objects in space, but also the possible shapes of a spatial figure.

Hermann Weyl gave an intrinsic definition for differentiable manifolds in his lecture course on Riemann surfaces in 1911–1912, opening the road to the general concept of a topological space that followed shortly.

During the 1930s Hassler Whitney and others clarified the foundational aspects of the subject, and thus intuitions dating back to the latter half of the 19th century became precise, and developed through differential geometry and Lie group theory.

William Thurston's geometrization program, formulated in the 1970s, provided a far-reaching extension of the Poincaré conjecture to the general three-dimensional manifolds.

Four-dimensional manifolds were brought to the forefront of mathematical research in the 1980s by Michael Freedman and in a different setting, by Simon Donaldson, who was motivated by the then recent progress in theoretical physics (Yang–Mills theory), where they serve as a substitute for ordinary 'flat' spacetime.

Important work on higher-dimensional manifolds, including analogues of the Poincaré conjecture, had been done earlier by René Thom, John Milnor, Stephen Smale and Sergei Novikov.

In particular, the same underlying topological manifold can have several mutually incompatible classes of differentiable functions and an infinite number of ways to specify distances and angles.

This allows one to define various notions such as length, angles, areas (or volumes), curvature and divergence of vector fields.

Many familiar curves and surfaces, including for example all n-spheres, are specified as subspaces of a Euclidean space and inherit a metric from their embedding in it.

In dimensions two and higher, a simple but important invariant criterion is the question of whether a manifold admits a meaningful orientation.

Although there is no way to do so physically, it is possible (by considering a quotient space) to mathematically merge each antipode pair into a single point.

In higher-dimensional manifolds genus is replaced by the notion of Euler characteristic, and more generally Betti numbers and homology and cohomology.

This leads to such functions as the spherical harmonics, and to heat kernel methods of studying manifolds, such as hearing the shape of a drum and some proofs of the Atiyah–Singer index theorem.