Music of Afghanistan

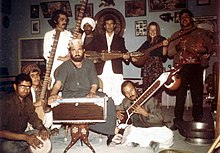

Afghanistan has a rich musical heritage[1] and features a mix of Persian melodies, Indian compositional principles, and sounds from ethnic groups such as the Pashtuns, Tajiks and Hazaras.

[3][4] Since their resurgence to power on 15 August 2021, Taliban authorities in Afghanistan have implemented a strict ban on music, particularly at weddings, social gatherings, and on radio and television.

Koran recitation is an important kind of unaccompanied religious performance, as is the ecstatic Zikr ritual of the Sufis which uses songs called na't, and the Shi'a solo and group singing styles like mursia, manqasat, nowheh and rowzeh.

The Chishti Sufi sect of Kabul is an exception in that they use instruments like the rubab, tabla also harmonium in their worship; this music is called tatti ("food for the soul").

One of the best known songs is "Da Zamong Zeba Watan" ("This is our beautiful homeland" in Pashto) by Ustad Awalmir, sung sometime in the 1970s.

These different traditions and styles evolved over centuries in the context of a society with highly diverse ethnic, linguistic, regional, religious, and class distinctions.

Although it is common practice to classify Afghan music along linguistic and regional lines (i.e. Pashto, Persian, Logari, Shomali, etc.

The classical musical form of Afghanistan is called klasik, which includes both instrumental and vocal and belly dancing ragas, as well as Tarana and Ghazals.

[7] They maintain cultural and personal ties with India—through discipleship or intermarriage—and they use the Hindustani musical theories and terminology, for example raga (melodic form) and tala (rhythmic cycle).

Sarban chose poetry from the great classical Persian/Dari poets and set them to compositions which incorporated elements of Western jazz and belle chanson with the mohali (regional) traditions of Afghanistan.

Sarban's musical style was effectively adopted by Ahmad Zahir, Ahmad Wali, Nashenas, Afsana, Seems Tarana, Jawad Ghaziyar, Farhad Darya, and numerous other Afghan singers, and transformed into a genuine recognizable Afghan musical style.

[11] The rubab has a double-chambered body carved from mulberry wood, which is chosen to give the instrument its distinct timbre.

Famous players of the rubab are Mohammad Omar, Essa Kassemi, Homayun Sakhi, and Mohammed Rahim Khushnawaz.

Notable dombura players in Afghanistan include Dilagha Surood, Naseer Parwani, Dawood Sarkhosh, Mir Maftoon and Safdar Tawakoli.

The following is an incomplete list of classical Afghan musicians who have been honored as an ustad: In 1925, Afghanistan began radio broadcasting, but its station was destroyed in 1929.

Amateur singers included Farhad Darya, Ahmad Zahir, Ustad Davood Vaziri, Nashenas (Dr. Sadiq Fitrat), Ahmad Wali, Zahir Howaida, Rahim Mehryar, Mahwash, Haidar Salim, Ehsan Aman, Hangama, Parasto, Naghma, Mangal, Sarban, Qamar Gula and others.

Ahmad Zahir was among Afghanistan's most famous singers; throughout the 60s and 70s he gained national and international recognition in countries like Iran and Tajikistan.

[20] During the 1990s, the Afghan Civil War caused many musicians to flee, and subsequently the Taliban government banned instrumental music and much public music-making.

Exiled musicians from the famous Kharabat district of Kabul set up business premises in Peshawar, Pakistan, where they continued their musical activities.

[21] In addition, traditional Pashtun music (especially in the southeast of the country) entered a period of "golden years", according to a prominent spokesman for Afghan Ministry of Interior, Lutfullah Mashal.

Metal music was represented by District Unknown, who as a band no longer exist and have moved to various parts of the world, from the United Kingdom to the US.

[26] It inherits much of the style of traditional hip hop, but puts added emphasis on rare cultural sounds.

[29] Sonita Alizadeh is another female Afghan rapper, who has gained notoriety for writing music protesting forced marriages.