Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War

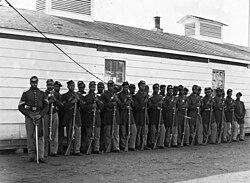

Throughout the course of the war, black soldiers served in forty major battles and hundreds of more minor skirmishes; sixteen African Americans received the Medal of Honor.

[2] For the Confederacy, both free and enslaved black Americans were used for manual labor, but the issue of whether to arm them, and under what terms, became a major source of debate within the Confederate Congress, the President's Cabinet, and C.S.

they scream, or the cause of the Union is gone...and yet these very officers, representing the people and the Government, steadily, and persistently refuse to receive the very class of men which have a deeper interest in the defeat and humiliation of the rebels than all others.

[8] On July 17, 1862, the U.S. Congress passed two statutes allowing for the enlistment of "colored" troops (African Americans)[9] but official enrollment occurred only after the effective date of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863.

[10] In March 1863, upon hearing that Andrew Johnson was open to recruiting blacks in Tennessee, Abraham Lincoln wrote him encouragement: "The colored population is the great available, and yet unavailed of, force for restoring the Union.

[1]: 16 Notably, their mortality rate was significantly higher than that of white soldiers: [We] find, according to the revised official data, that of the slightly over two millions troops in the United States Volunteers, over 316,000 died (from all causes), or 15.2%.

[5]: 165–167 In early 1861, General Butler was the first known Union commander to use black contrabands, in a non-combatant role, to do the physical labor duties, after he refused to return escaped slaves, at Fort Monroe, Virginia, who came to him for asylum from their masters, who sought to capture and reenslave them.

Because of the harsh working conditions and the extreme brutality of their Cincinnati police guards, the Union Army, under General Lew Wallace, stepped in to restore order and ensure that the black conscripts received the fair treatment due to soldiers, including the equal pay of privates.

Jane E. Schultz wrote of the medical corps that Approximately 10 percent of the Union's female relief workforce was of African descent: free blacks of diverse education and class background who earned wages or worked without pay in the larger cause of freedom, and runaway slaves who sought sanctuary in military camps and hospitals.

[citation needed] In October 1862, African-American soldiers of the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry, in one of the first engagements involving black troops, silenced their critics by repulsing attacking Confederate guerrillas at the Skirmish at Island Mound, Missouri, in the Western Theatre.

[18] On June 7, 1863, a garrison consisting mostly of black troops assigned to guard a supply depot during the Vicksburg Campaign found themselves under attack by a larger Confederate force.

Recently recruited, minimally trained, and poorly armed, the black soldiers still managed to successfully repulse the attack in the ensuing Battle of Milliken's Bend with the help of federal gunboats from the Tennessee river, despite suffering nearly three times as many casualties as the rebels.

Despite the defeat, the unit was hailed for its valor, which spurred further African-American recruitment, giving the Union a numerical military advantage from a large segment of the population the Confederacy did not attempt to exploit until too late in the closing days of the War.

On April 12, 1864, at the Battle of Fort Pillow, in Tennessee, Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest led his 2,500 men against the Union-held fortification, occupied by 292 black and 285 white soldiers.

After driving in the Union pickets and giving the garrison an opportunity to surrender, Forrest's men swarmed into the Fort with little difficulty and drove the Federals down the river's bluff into a deadly crossfire.

Wild defiantly refused, responding with a message stating "Present my compliments to General Fitz Lee and tell him to go to hell.” In the ensuing battle, the garrison force repulsed the assault, inflicting 200 casualties with a loss of just 6 killed and 40 wounded.

[5]: 198 General Daniel Ullman, commander of the Corps d'Afrique, remarked "I fear that many high officials outside of Washington have no other intention than that these men shall be used as diggers and drudges.

It is an omnipresent spy system, pointing out our valuable men to the enemy, revealing our positions, purposes, and resources, and yet acting so safely and secretly that there is no means to guard against it.

Even in the heart of our country, where our hold upon this secret espionage is firmest, it waits but the opening fire of the enemy's battle line to wake it, like a torpid serpent, into venomous activity.

[34] Secretary of the Navy, Gideon Wells in a terse order, pointed out the following; It is not the policy of this Government to invite or encourage this kind of desertion and yet, under the circumstances, no other course...could be adopted without violating every principle of humanity.

[36] In contrast to the Army, the Navy from the outset not only paid equal wages to white and black sailors, but offered considerably more for even entry-level enlisted positions.

[2] THE BATTALION from Camps Winder and Jackson, under the command of Dr. Chambliss, including the company of colored troops under Captain Grimes, will parade on the square on Wednesday evening, at 4* o'clock.

[46] Two companies were raised from laborers of two local hospitals-Winder and Jackson-as well as a formal recruiting center created by General Ewell and staffed by Majors James Pegram and Thomas P.

[47]: 62–63 Bruce Levine wrote that "Nearly 40% of the Confederacy's population were unfree... the work required to sustain the same society during war naturally fell disproportionately on black shoulders as well.

"[47]: 62 Naval historian Ivan Musicant wrote that blacks may have possibly served various petty positions in the Confederate Navy, such as coal heavers or officer's stewards, although records are lacking.

As the Union saw victories in the fall of 1862 and the spring of 1863, however, the need for more manpower was acknowledged by the Confederacy in the form of conscription of white men, and the national impressment of free and enslaved blacks into laborer positions.

There would be no recruits awaiting the enemy with open arms, no complete history of every neighborhood with ready guides, no fear of insurrection in the rear...[2] Cleburne's proposal received a hostile reception.

Recognizing slave families would entirely undermine the economic foundation of slavery, as a man's wife and children would no longer be salable commodities, so his proposal veered too close to abolition for the pro-slavery Confederacy.

"[63][64][2] It was sent to Confederate President Jefferson Davis anyway, who refused to consider Cleburne's proposal and ordered the report kept private as discussion of it could only produce "discouragement, distraction, and dissension."

The unit was short lived, and never saw combat before forced to disband in April 1862 after the Louisiana State Legislature passed a law that reorganized the militia into only "...free white males capable of bearing arms.