Iron metallurgy in Africa

[1] Whether iron metallurgy in Sub-Saharan Africa originated as an independent innovation or a product of technological diffusion remains a point of contention between scholars.

[1][7][8] Although a number of scholars have scrutinized these dates on methodological and theoretical grounds,[5][9][10] others contend that they undermine the diffusionist model for the origins of iron metallurgy in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The Bantu expansion spread the technology to Eastern and Southern Africa between 500 BCE and 400 CE, as shown in the Urewe culture.

[8] According to archaeometallurgist Manfred Eggert, "Carthage cannot be reliably considered the point of origin for sub-Saharan iron ore reduction.

This funded both the conference on early iron in Africa and the Mediterranean[22] and a volume, published by UNESCO, that generated some controversy because it included only authors sympathetic to the independent-invention view.

[28] Two reviews of the evidence from the mid-2000s found technical flaws in the studies claiming independent invention, raising three major issues.

This would make Oboui the oldest iron-working site in the world, and more than a thousand years older than any other dated evidence of iron in Central Africa.

Additionally, Holl, regarding the state of preservation, argues that this observation was based on published illustrations representing a small unrepresentative number of atypically well-preserved objects selected for publication.

[11] In 2014, archaeo-metallurgist Manfred Eggert argued that, though still inconclusive, the evidence overall suggests an independent invention of iron metallurgy in sub-Saharan Africa.

[8] While the origins of iron smelting are difficult to date by radiocarbon, there are fewer problems with using it to track the spread of ironworking after 400 BCE.

In the 1960s it was suggested that iron working was spread by speakers of Bantu languages, whose original homeland has been located by linguists in the Benue River valley of eastern Nigeria and Western Cameroon.

Although some assert that no words for iron or ironworking can be traced to reconstructed proto-Bantu,[39] place-names in West Africa suggest otherwise, for example (Okuta) Ilorin, literally "site of iron-work".

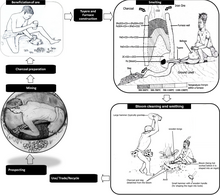

W.W. Cline's compilation of eye-witness records of bloomery iron smelting over the past 250 years in Africa[43] is invaluable, and has been supplemented by more recent ethnoarchaeological and archaeological studies.

Precolonial iron workers in present South Africa even smelted iron-titanium ores that modern blast furnaces are not designed to use.

The oldest natural-draft furnaces yet found are in Burkina Faso and date to the seventh/eight centuries [47] The large masses of slag (10,000 to 60,000 tons) noted in some locations in Togo, Burkina Faso and Mali reflect the great expansion of iron production in West Africa after 1000 CE that is associated with the spread of natural-draft furnace technology.

There is also evidence that carbon steel was made in Western Tanzania by the ancestors of the Haya people as early as 2,300-2,000 years ago by a complex process of "pre-heating" allowing temperatures inside a furnace to reach up to 1800°C.

Blacksmiths still work in rural areas of Africa to make and repair agricultural tools, but the iron that they use is imported, or recycled from old motor vehicles.

Iron did not replace other materials, such as stone and wooden tools, but the quantity of production and variety of uses met were significantly high by comparison.

Some were lower in society due to the aspect of manual labour and associations with witchcraft, for example in the Maasai and Tuareg (Childs et al. 2005 pg 288).

For example, an excavation at the royal tomb of King Rugira (Great Lakes, Eastern Africa) found two iron anvils placed at his head (Childs et al. 2005, p. 288 in Herbert 1993:ch.6).

Ironworkers engaged in rituals designed to encourage good production and to ward off bad spirits, including song and prayers, plus the giving of medicines and sacrifices.

[59] Men who possessed the knowledge and skills to work with iron, held a high social status and were often revered for their expertise.

The ideology behind this was that, these 'Blacksmiths' possessed some spiritual and super human abilities which enabled them to extract the bloom from iron ore, eventually earning them a higher place of social status.