Copper metallurgy in Africa

[2] The principal evidence for this claim is an Egyptian outpost established in Buhen (near today's Sudanese-Egyptian border) around 2600 BC to smelt copper ores from Nubia.

Alongside this, a crucible furnace dating to 2300–1900 BC for bronze casting has been found at the temple precinct at Kerma (in present-day northern Sudan), however the source of the tin remains unknown.

Radiocarbon dates from the Grotte aux Chauves-souris mine shows that the extraction and smelting of malachite goes back to the early fifth century BC.

A number of copper artifacts—including arrow points, spearheads, chisels, awls and plano-convex axes as well as bracelets, bead and earrings—were found at Neolithic sites in the region.

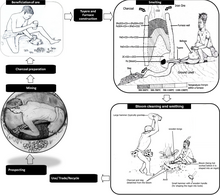

Complex deep-mining methods and special tools were not needed, because oxides were structurally weakened by decomposition processes and contained the most desirable ores, and although the techniques used seemed to be simple, Africans were very successful in extracting large quantities of high-grade ore.[4] The copper mines themselves were most frequently open stopes or open stopes with shafts.

[4] In sub-Saharan West Africa, there were only two known source of copper that were commercially viable: Dkra near Nioro, Mali and Takedda in Azelik, Niger.

[5] The discovery of copper metallurgy in the Akjoujt region in Mauritania [6][7] and the Eghazzer basin[8][9] dated to the second and early first millennium BCE shook the foundation of that consensus.

In all the other areas reviewed in this article, however, iron metallurgy was adopted directly by Late Stone Age mixed-farming and horticulturalist communities.

“The mining and smelting of copper ore appears to have arisen independently in Asia Minor, Eastern Europe, and Egypt between 5000 and 4000 BC” [11] .

He outlines a number of elements suggesting a link between the Akjoujt copper metallurgy, Western Europe Early Bronze Age, and Phoenician North Africa.

Iron technology may have been introduced along similar networks by the turn of the first millennium BC, although additional stimulus was provided by the new links to the northern coast.

The use of copper in the Iron Age of Central Africa was produced because of indigenous or internal demand rather than those from outside, and it is thought to be a sensitive sign of political and social change.

Archaeological and documentary sources may skew the record in favor of nonperishable elements of culture and not give enough credit to pastoral and mixed farming activities that were needed to sustain these Iron Age populations.

[21] Tswana towns of the pre-colonial period in South Africa, such as the Tlokwa capital at Marothodi near the Pilanesberg National Park, demonstrate a continuation of native copper production into the early nineteenth century.