Traditional African religions

They generally seek to explain the reality of personal experience by spiritual forces which underpin orderly group life, contrasted by those that threaten it.

[22] Native African religions are centered on ancestor worship, the belief in a spirit world, supernatural beings and free will (unlike the later developed concept of faith).

Forms of polytheism was widespread in most of ancient African and other regions of the world, before the introduction of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism.

Ancestors can offer advice and bestow good fortune and honor to their living descendants, but they can also make demands, such as insisting that their shrines be properly maintained and propitiated.

Monotheism does not reflect the multiplicity of ways that the traditional African spirituality has conceived of deities, gods, and spirit beings.

[34] West and Central African religious practices generally manifest themselves in communal ceremonies or divinatory rites in which members of the community, overcome by force (or ashe, nyama, etc.

In this state, depending upon the region, drumming or instrumental rhythms played by respected musicians (each of which is unique to a given deity or ancestor), participants embody a deity or ancestor, energy or state of mind by performing distinct ritual movements or dances which further enhance their elevated consciousness.

[35] When this trance-like state is witnessed and understood, adherents are privy to a way of contemplating the pure or symbolic embodiment of a particular mindset or frame of reference.

Such separation and subsequent contemplation of the nature and sources of pure energy or feelings serves to help participants manage and accept them when they arise in mundane contexts.

Also, this practice can give rise to those in these trances uttering words which, when interpreted by a culturally educated initiate or diviner, can provide insight into appropriate directions which the community (or individual) might take in accomplishing its goal.

[43] The deities and spirits are honored through libation or sacrifice of animals, vegetables, cooked food, flowers, semi-precious stones, or precious metals.

[44] Traditional African religions embrace natural phenomena – ebb and tide, waxing and waning moon, rain and drought – and the rhythmic pattern of agriculture.

All aspects of weather, thunder, lightning, rain, day, moon, sun, stars, and so on may become amenable to control through the cosmology of African people.

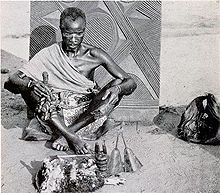

The practice of casting may be done with small objects, such as bones, cowrie shells, stones, strips of leather, or flat pieces of wood.

In Xhosa, the latter term is used, but is often meant in a more philosophical sense to mean "the belief in a universal bond of sharing that connects all humanity".

While the nuances of these values and practices vary across different ethnic groups, they all point to one thing – an authentic individual human being is part of a larger and more significant relational, communal, societal, environmental and spiritual world.

Examples include social behaviors such as the respect for parents and elders, raising children appropriately, providing hospitality, and being honest, trustworthy, and courageous.

In some traditional African religions, morality is associated with obedience or disobedience to God regarding the way a person or a community lives.

For the Kikuyu, according to their primary supreme creator, Ngai, acting through the lesser deities is believed to speak to and be capable of guiding the virtuous person as one's conscience.

[49] Some sacred or holy locations for traditional religions include but not limited to Nri-Igbo, the Point of Sangomar, Yaboyabo, Fatick, Ife, Oyo, Dahomey, Benin City, Ouidah, Nsukka, Kanem-Bornu, Igbo-Ukwu, and Tulwap Kipsigis, among others.

[51] In contemporary Africa, many people identify with both traditional African religions and either Christianity or Islam, practicing elements of both in a form of religious duality.

This syncretism is evident in rituals, festivals, and the spiritual lives of individuals who draw on the strengths of both their indigenous traditions and the newer religions.

However, tensions have arisen, particularly where aggressive proselytism by Christian or Islamic groups has sought to replace traditional African religions entirely.

[56][57] Because of persecution and discrimination, as well as incompatibility with traditional society, culture and native beliefs, the Dinka people largely rejected or ignored Islamic and Christian teachings.

[58] Bandama and Babalola (2023) states:[59] The view of science as "embedded practice," intimately connected with ritual, for example, is considered "ascientific," "pseudo-science," or "magic" in Western perspective.

In the Ile-Ife pantheon, for example, Olokun – the goddess of wealth – is considered the patron of the glass industry and is therefore consulted.

Afro-American religions involve ancestor worship and include a creator deity along with a pantheon of divine spirits such as the Orisha, Loa, Vodun, Nkisi and Alusi, among others.