Africville

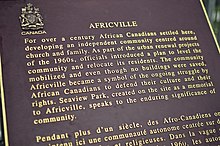

The community has become an important symbol of Black Canadian identity, as an example of the "urban renewal" trend of the 1960s that razed similarly racialized neighbourhoods across Canada, and the struggle against racism.

During the 20th century, Halifax neglected the community, failing to provide basic infrastructure and services such as roads, water, and sewerage.

The residents of Africville struggled with poverty and poor health conditions as a result, and the community's buildings became badly deteriorated.

[3] After years of protest and investigations, in 2010 the Halifax Council ratified the Africville Apology under an arrangement with the federal government to compensate descendants and their families who had been evicted from the area.

[4] First known as the Campbell Road Settlement,[5] Africville began as a small, poor, self-sufficient rural community of about 50 people during the 19th century.

"[9] Strangers later moved into Africville to take advantage of its unregulated status, selling illicit liquor and sex, largely to the mass of transient soldiers and sailors passing through Halifax.

[11]: 44–45 Elevated land to the south protected Africville from the direct blast of the explosion and the complete destruction that levelled the neighbouring community of Richmond.

Four Africville residents (as well as one Mi'kmaq woman visiting from Queens County, Nova Scotia) were killed by the explosion.

[12] A doctor on a relief train arriving at Halifax noted Africville residents "as they wandered disconsolately around the ruins of their still standing little homes.

[14][page needed] Beginning in the early 20th century around the Great War, more people had moved there, drawn by jobs in industries and related facilities developed nearby.

From the mid-19th century, the City of Halifax located its least desirable facilities in the Africville area, where the people had little political power and property values were low.

A prison was built there in 1853, an infectious disease hospital in 1870, as well as a slaughterhouse, and a depository for fecal waste from nearby Russellville.

[15] Scholars have concluded that the razing of Africville was a confluence of "overt and hidden racism, the progressive impulse in favour of racial integration, and the rise of liberal-bureaucratic social reconstruction ideas.

"[16] During the 1940s and 1950s in different parts of Canada, the federal, provincial, and municipal governments were working together for urban renewal, particularly after the Allied victory in World War II: there was energy to redevelop areas classified as slums and relocate the people to new and improved housing.

Other notable racialized neighbourhoods razed under the banner of urban renewal include The Ward in Toronto, Rooster Town in Winnipeg, and The Bog in Charlottetown.

Many former residents believe that the city council had no plans to turn Africville into an industrial site and that racism was the basis of the community's destruction.

Because of the city's continued negative response to the people of Africville, the community failed to develop, and this failure was then used as a rationale to destroy it.

[20] On 20 November 1967, the church at Africville was demolished at night to avoid controversy, a year before the city officially possessed the building.

[21] There is controversy around the documentation, which shows the church was sold in 1968; the page has been edited by hand to forge the sale as a year earlier.

In light of the controversy related to the relocation, the city of Halifax created the Seaview Memorial Park on the site in the 1980s, preserving it from development.

Eddie Carvery has been living on the Africville site since 1970 in protest of the razing despite city officials seizing his trailers several times.

[28] Halifax mayor Peter Kelly offered land, some money, and various other services for a replica of the Seaview African United Baptist Church.

In May 2005, New Democratic Party of Nova Scotia MLA Maureen MacDonald introduced a bill in the provincial legislature called the Africville Act.

[31] A building designed to mimic the Seaview African United Baptist Church, demolished in 1969, was erected in the summer of 2011 to serve as a museum and historic interpretation centre.

[32][33] The opening ceremonies included a gospel concert, several church services, and the release of a compilation audio album with archival recordings of songs sung in Africville.