Agnes Arber

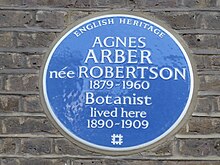

Agnes Arber FRS (née Robertson; 23 February 1879 – 22 March 1960) was a British plant morphologist and anatomist, historian of botany and philosopher of biology.

Her father gave her regular drawing lessons during her early childhood, which later provided her with the necessary skills to illustrate her scientific publications herself.

[3] At the age of eight Robertson began attending the North London Collegiate School founded and run by Frances Buss, one of the leading proponents for girls' education.

[4] It was here that Robertson first met Ethel Sargant, a plant morphologist who gave regular presentations to the school science club.

[3] After finishing her Cambridge degree in 1902 Robertson worked in the private laboratory of Ethel Sargant for a year, before returning to University College, London as holder of the Quain Studentship in Biology.

[3] Arber was awarded a Research Fellowship from Newnham College in 1912 and published her first book Herbals, their origin and evolution in the same year.

Arber maintained a small laboratory in a back room of her house from then until she stopped performing bench research in the 1940s and turned to philosophical study.

Sargant employed Arber between 1902 and 1903 as a research assistant working on seedling structures, during which time in 1903 she published her first paper 'Notes on the anatomy of Macrozamia heteromera' in Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society.

[4] Whilst at University College London Arber conducted research on the gymnosperm group of plants, producing several papers on their morphology and anatomy.

Arber links the emergence and development of botany as a discipline within natural history with the evolution of plant descriptions, classifications and identifications seen in Herbals during this period.

Arber was able to consult the large collection of printed Herbals in the library of the Botany School at Cambridge as part of her research for this work.

[2] Arber focused her research on the anatomy and morphology of the monocot group of plants, which she had originally been introduced to by Ethel Sargant.

Arber addressed this by creating a distinction between "pure" and "applied" morphology, with her work focusing on comparative anatomy to investigate questions concerning significant topics such as constructing phylogenies, instead of using traditional views of plant structure.

After the 1927 closure of the Balfour Laboratory Arber set up a small laboratory in a back room of her house to conduct her research, after the resident head of the Botany School Professor Albert Seward claimed there was no space in the School for Arber to continue her research using its facilities.

[4] Arber had been introduced to the idea of private research from her time spent with Ethel Sargant in 1902–1903, and from later comments to members of Girton College Natural Sciences club and in letters to friends she stated she liked working at home due to challenges posed by independent research, despite not originally making the choice herself.

Arber published work on historical botanists, including a comparison between Nehemiah Grew and Marcello Malpighi in 1942, John Ray in 1943 and Sir Joseph Banks in 1945.

She mentions: “the leaf is a partial-shoot, revealing an inherent urge towards becoming a whole shoot, but never actually attaining this goal, since radial symmetry and the capacity for apical growth suffer inhibition”.

[9] The parallelism of leaf and shoot dates back to Goethe, who first described compound leaves as in "reality branches, the buds of which cannot develop, since the common stalk is too frail".

Recent developmental genetic evidence has supported aspects of the partial shoot-theory of the leaf, especially in the case of compound leaves.

The book is a wide-ranging and syncretic survey, drawing on literary, scientific, religious, mystical and philosophical traditions, incorporating Buddhist, Hindu and Taoist philosophy with European philosophy.,[4] in pursuit of a discussion of the mystical experience which Arber defines as "that direct and unmediated contemplation which is characterised by a peculiarly intense awareness of a Whole as the Unity of all things".

[14] In May 2024, a new sponsored Agnes Arber PhD thesis prize in comparative biology at the University of Cambridge was created.

Professor Sam Brockington, of Cambridge University Botanic Gardens, said that he hoped the prize "will support the next generation of pioneering botanists, following in the footsteps of Agnes".