Marcello Malpighi

Marcello Malpighi (10 March 1628 – 30 November 1694) was an Italian biologist and physician, who is referred to as the "founder of microscopical anatomy, histology and father of physiology and embryology".

[2] The use of the microscope enabled Malpighi to discover that insects do not use lungs to breathe, but small holes in their skin called tracheae.

In his autobiography, Malpighi speaks of his Anatome Plantarum, decorated with the engravings of Robert White, as "the most elegant format in the whole literate world.

He joined the school of anatomy under Bartolomeo Massari and was one of nine students who met at the home of the master to conduct dissections.

There Malpighi began his lifelong friendship with Giovanni Borelli, mathematician and naturalist, who was a prominent supporter of the Accademia del Cimento, one of the first scientific societies.

Family responsibilities and poor health prompted Malpighi's return in 1659 to the University of Bologna, where he continued to teach and do research with his microscopes.

In 1653, his father, mother, and grandmother being dead, Malpighi left his family villa and returned to the University of Bologna to study anatomy.

Based on this research, he wrote some Dialogues against the Peripatetics and Galenists (those who followed the precepts of Galen and were spearheaded at the University Bologna by fellow physician but inveterate foe Giovanni Girolamo Sbaraglia), which were destroyed when his house burned down.

Retiring from university life to his villa in the country near Bologna in 1663, he worked as a physician while continuing to conduct experiments on the plants and insects he found on his estate.

Although he accepted temporary chairs at the universities of Pisa and Messina, throughout his life he continuously returned to Bologna to practice medicine, a city that repaid him by erecting a monument in his memory after his death.

[11] These letters served as social connections for the medical practices he performed, allowing his ideas to reach the public even in the face of criticism.

[11] Malpighi did not abandon traditional substances or treatments, but he did not employ their use simply based on past experiences that did not draw from the nature of the underlying anatomy and disease process.

Marcello Malpighi is buried in the church of Santi Gregorio e Siro, in Bologna, where nowadays can be seen a marble monument to the scientist with an inscription in Latin remembering – among other things – his "SUMMUM INGENIUM / INTEGERRIMAM VITAM / FORTEM STRENUAMQUE MENTEM / AUDACEM SALUTARIS ARTIS AMOREM" (great genius, honest life, strong and tough mind, daring love for the medical art).

[14] Malpighi's first attempt at examining circulation in the lungs was in September 1660, with the dissection of sheep and other mammals where he would inject black ink into the pulmonary artery.

[15] Tracing the inks distribution through the artery to the veins in the animal's lungs however, the chosen sheep/mammal's large size was limiting for his observation of capillaries as they were too small for magnification.

[16] Malpighi's frog dissection in 1661, proved to be a suitable size that could be magnified to display the capillary network not seen in the larger animals.

[17] Furthering his analysis of the lungs, Malpighi identified the airways branched into thin membraned spherical cavities which he likened to honeycomb holes surrounded by capillary vessels, in his 1661 work "De pulmonibus observationes anatomicae".

[21] Malpighi had success in tracing the ontogeny of plant organs, and the serial development of the shoot owing to his instinct shaped in the sphere of animal embryology.

Because Malpighi was concerned with teratology (the scientific study of the visible conditions caused by the interruption or alteration of normal development) he expressed grave misgivings about the view of his contemporaries that the galls of trees and herbs gave birth to insects.

Malpighi also postulated about the embryotic growth of humans, written in a letter to Girolamo Correr, a patron of scientists, Malphighi suggested that all the components of the circulatory system would have been developed at the same time in embryo.

[22] His discoveries helped to illuminate philosophical arguments surrounding the topics of emboîtment, pre-existence, preformation, epigenesis, and metamorphosis.

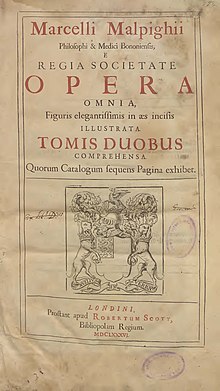

He taught medicine in the Papal Medical School and wrote a long treatise about his studies which he donated to the Royal Society of London.

Marcello Malpighi died of apoplexy (an old-fashioned term for a stroke or stroke-like symptoms) in Rome on 30 November 1694, at the age of 66.