Agnes of Courtenay

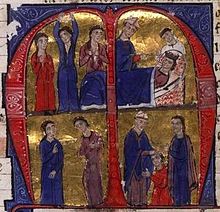

Agnes of Courtenay (c. 1136 – c. 1184) was a Frankish noblewoman who held considerable influence in the Kingdom of Jerusalem during the reign of her son, King Baldwin IV.

Agnes selected government officials and influenced succession by choosing husbands for both Sibylla and Isabella, Amalric's daughter by his second wife, Maria Comnena.

Her father, Count Joscelin II of Edessa, was the second cousin of Queen Melisende of Jerusalem, Princess Alice of Antioch, and Countess Hodierna of Tripoli, connecting her to all the Frankish Catholic rulers of the Latin East.

Her mother found herself unable to defend the remnants of the County of Edessa and sold them to the Byzantine emperor, Manuel I Komnenos, for an annual pension to be paid to herself and her children, Agnes and Joscelin III.

[1] In 1157, Agnes came to the Kingdom of Jerusalem, where she married Queen Melisende's younger son, Count Amalric,[1] and became countess of Jaffa and Ascalon.

[2][3] Though she was penniless, historian Bernard Hamilton considers Agnes to have been the most suitable bride for Amalric in the crusader states due to her high birth.

[2] The High Court may also have that believed Agnes, like her mother-in-law, would wield power in the government or that Amalric could make a politically and financially better match; if so, they were to be proven right on both counts.

[2] The reason was so flimsy that William of Tyre, who had been abroad at the time, had to ask Agnes's aunt Stephanie, abbess of St Mary Major, to explain it to him.

[5][8] The ecclesiastical court granted Amalric's request that their children, Sibylla and Baldwin, be legitimized, and that Agnes be absolved of any moral condemnation.

[2] Hamilton concludes from Agnes's ability to nearly instantly contract such an advantageous marriage that the High Court did not refuse to recognize her as queen due to a moral scandal.

[19] Ernoul, a protegé of Amalric's Queen Maria,[18] accuses Agnes of love affairs with Heraclius[19] and Aimery of Lusignan, who was also on a steady rise to the highest position in the kingdom.

Hamilton believes that Joscelin, as an uncle with no claim to the throne, was a prudent choice; he proved both markedly competent and wholly loyal to the king.

[23] When it became apparent that Baldwin IV was indeed affected by leprosy and therefore precluded from marrying and siring children,[24] the question of the marriage of Agnes's daughter, Sibylla, became central to the royal government.

She was supposed to marry Duke Hugh III of Burgundy but, according to Ernoul, promised her hand to Baldwin of Ibelin on the condition that he paid his debt to the Muslim ruler of Egypt, Saladin.

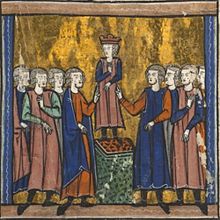

[28] William of Tyre tells about a coup attempt launched during the Holy Week in 1180 by Count Raymond III of Tripoli and Prince Bohemond III of Antioch; Hamilton concludes that they likely intended to depose Baldwin IV, install Sibylla, and have her marry a man of their own choosing (probably Baldwin of Ibelin), thereby removing the Courtenays from power.

Hamilton holds that two distinct parties appeared only after Sibylla's marriage to Guy and centred on Baldwin IV's paternal relatives (Raymond of Tripoli, Bohemond of Antioch, and Maria Komnene and the Ibelins) and maternal relatives (Agnes and Reginald of Sidon, Sibylla and Guy, Joscelin, and Reginald of Châtillon), of whom the king supported the latter.

[19] In October 1180, Baldwin had his younger half-sister, Isabella, daughter of Amalric by Maria Comnena, betrothed to Humphrey IV of Toron.

[30] Balian, who had married Isabella's mother, Queen Maria, and his brother Baldwin of Ibelin were also thus prevented from using the young princess to conspire against Agnes's children.

[38] Baldwin, however, soon became disillusioned with Guy's character and capability and decided to depose him from the regency in late 1183 at a council convened to deal with Saladin's siege of Kerak, where Isabella was marrying Humphrey.

[45] Raymond may have hoped to present himself as the suitable heir;[45] if so, the countess thwarted his plan by proposing her grandson, Baldwin V, Sibylla's son by William of Montferrat, and the boy was duly crowned.

[47] He passed by Toron in September 1184 and remarked, in the language commonly used by Muslims of the time when referring to Christians, that the area "belongs to the sow known as queen who is the mother of the pig who is lord of Acre–may God destroy it".

Baldwin V's death in mid-1186 caused a succession crisis in which Agnes played no part; on 21 October, Guy, now king after all, acknowledged that Joscelin had satisfactorily executed his sister's last will.

[18] In her rise from a powerless repudiated wife to the person who selected husbands for both potential heiresses and who appointed chief lay and ecclesiastical officeholders in the kingdom he sees evidence of "clearly a remarkably clever woman".

[3] The view that she exploited her son's illness to fill the court with corrupt officials at the expense of capable men comes from William of Tyre, who never forgave her for her role in his defeat in the patriarchal election; he calls her a "woman who was relentless in her acquisitiveness and truly hateful to God".