Agriculturalism

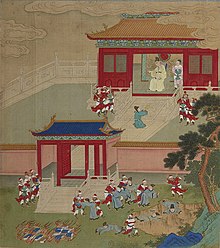

Throughout this period, competing states, seeking to war with one another and unite China as a single country, patronized philosophers, scholars, and teachers.

The competition by scholars for the attention of rulers led to the development of different schools of thought, and the emphasis on recording teachings into books encouraged their spread.

[2] The Agriculturalists also emphasized the role of Shennong, the divine farmer, a semi-mythical ruler of early China credited by the Chinese as the inventor of agriculture.

The Agriculturalist king is not paid by the government through its treasuries; his livelihood is derived from the profits he earns working in the fields and cooking his own meals, not his leadership.

How can he be a worthy ruler?Unlike the Confucians, the Agriculturalists did not believe in the division of labour, arguing instead that the economic policies of a country need to be based upon an egalitarian self sufficiency.

They suggested that people should be paid the same amount for the same services, a policy criticized by the Confucians as encouraging products of low quality, which "destroys the earnest standards of craftmanship.

"[7] Agriculturalism was criticized extensively by rival philosophical schools, including the Mohist Mo Zi, the Confucian Mencius, and Yang Zhu.

[2] Mencius criticized its chief proponent Xu Xing for advocating that rulers should work in the fields with their subjects, arguing that the Agriculturalist egalitarianism ignored the division of labour central to society.