Degrowth

Policy should instead focus on economic and social metrics such as life expectancy, health, education, housing, and ecologically sustainable work as indicators of both ecosystems and human well-being.

[13][14] Degrowth theory partly orients itself as a critique of green capitalism or as a radical alternative to the market-based, sustainable development goal (SDG) model of addressing ecological overshoot and environmental collapse.

[9] However, in a recent review of efforts toward Sustain Development Goals by the Council of Foreign Relations in 2023 it was found that progress toward 50% of the minimum viable SDG's have stalled and 30% of these verticals have reversed (or are getting worse, rather than better).

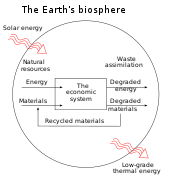

It represents the amount of biologically productive land and sea area required to regenerate the resources a human population consumes and to absorb and render harmless the corresponding waste.

For the world's population to attain the living standards typical of European countries, the resources of between three and eight planet Earths would be required with current levels of efficiency and means of production.

Additionally, alternative perspectives on degrowth include addressing perceived historical injustices perpetrated by the global North through centuries of colonization and exploitation, advocating for wealth redistribution.

[46] Further, degrowth draws on the critique of socialist feminists like Silvia Federici and Nancy Fraser claiming that capitalist growth builds on the exploitation of women's work.

[51] Furthermore, degrowth draws on materialist ecofeminisms that state the parallel of the exploitation of women and nature in growth-based societies and proposes a subsistence perspective conceptualized by Maria Mies and Ariel Salleh.

In 2022, Nick Fitzpatrick, Timothée Parrique and Inês Cosme conducted a comprehensive survey of degrowth literature from 2005 to 2020 and found 530 specific policy proposals with "50 goals, 100 objectives, 380 instruments".

Recent survey data suggest that degrowth is gaining popularity as a framework for policies that prioritize ecological sustainability and social well-being over perpetual economic growth.

[60][61] For instance, a pan-European survey reported that 61% of respondents favor post-growth approaches, and a study by the German Environment Agency found that 88% agree on the need to “live well regardless of economic growth.

[64] Moreover, widespread public support for measures such as job guarantees, universal basic income, and shorter working weeks—policies that seek to redistribute resources and reduce overconsumption—underscores a growing appetite for alternatives to traditional growth models.

Still, they are considered the first studies explicitly presenting economic growth as a key reason for the increase in global environmental problems such as pollution, shortage of raw materials, and the destruction of ecosystems.

[75] In September 2022, the Club of Rome released updated predictive models and policy recommendations in a general-audiences book titled Earth for all – A survival guide to humanity.

[16]: 195 Simultaneously, but independently, Georgescu-Roegen criticised the ideas of The Limits to Growth and Herman Daly's steady-state economy in his article, "Energy and Economic Myths", delivered as a series of lectures from 1972, but not published before 1975.

Instead, the neologism "degrowth" was coined to signify a deliberate political action to downscale the economy on a permanent, conscious basis—as in the prevailing French usage of the term—something good to be welcomed and maintained, or so followers believe.

[87] In January 1972, Edward Goldsmith and Robert Prescott-Allen—editors of The Ecologist—published A Blueprint for Survival, which called for a radical programme of decentralisation and deindustrialization to prevent what the authors referred to as "the breakdown of society and the irreversible disruption of the life-support systems on this planet".

They conclude that a change in economic paradigms is imperative to prevent environmental destruction, and suggest a range of ideas from the reformist to the radical, with the latter consisting of degrowth, eco-socialism and eco-anarchism.

"[94][95] In an opinion piece published in Al Jazeera, Jason Hickel states that this paper, which has more than 11,000 scientist cosigners, demonstrates that there is a "strong scientific consensus" towards abandoning "GDP as a measure of progress.

"[96] In a 2022 comment published in Nature, Hickel, Giorgos Kallis, Juliet Schor, Julia Steinberger and others say that both the IPCC and the IPBES "suggest that degrowth policies should be considered in the fight against climate breakdown and biodiversity loss, respectively".

[69] Although not explicitly called degrowth, movements inspired by similar concepts and terminologies can be found around the world, including Buen Vivir[103] in Latin America, the Zapatistas in Mexico, the Kurdish Rojava or Eco-Swaraj in India, and the sufficiency economy in Thailand.

The authors highlighted advances in ecological macroeconomic models, including testing post-growth policies, addressing GDP-linked welfare dependencies, and identifying systems to reduce resource use while enhancing wellbeing.

[110] A 2024 systematic review of degrowth studies over the past 10 years showed that most were of poor quality: almost 90% were opinions rather than analysis, few used quantitative or qualitative data, and even fewer ones used formal modelling; the latter used small samples or a focus on non-representative cases.

[112] A 2017 review of 91 articles (2006-2015) found a gradual shift from activist-driven narratives and conceptual essays to increasing academic rigor, branching into modelling, empirical assesments and the study of concrete implementations.

[4] Foster emphasizes that degrowth "is not aimed at austerity, but at finding a 'prosperous way down' from our current extractivist, wasteful, ecologically unsustainable, maldeveloped, exploitative, and unequal, class-hierarchical world.

[141] At the same time, some argue the widespread individualization promulgated by a capitalist political economy is a bad due to its undermining of solidarity, aligned with democracy as well as collective, secondary, and primary forms of caring,[142] and simultaneous encouragement of mistrust of others, highly competitive interpersonal relationships, blame of failure on individual shortcomings, prioritization of one's self-interest, and peripheralization of the conceptualization of human work required to create and sustain people.

In her examination of China following the Chinese Communist Revolution, Holmstrom notes that women were granted state-assisted freedoms to equal education, childcare, healthcare, abortion, marriage, and other social supports.

Doyal and Gough allege that the modern capitalist system is built on the exploitation of female reproductive labor as well as that of the Global South, and sexism and racism are embedded in its structure.

Beginning in the second term of the Reagan administration, the education system in the US was restructured to enforce neoliberal ideology by means of privatization schemes such as commercialization and performance contracting, implementation of standards and accountability measures incentivizing schools to adopt a uniform curriculum, and higher education accreditation and curricula designed to affirm market values and current power structures and avoid critical thought concerning the relations between those in power, ethics, authority, history, and knowledge.

[148][146][149] It has been pointed out that there is an apparent trade-off between the ability of modern healthcare systems to treat individual bodies to their last breath and the broader global ecological risk of such an energy and resource intensive care.