Agriculture in the Soviet Union

[citation needed] The forced collectivization and class war against (vaguely defined) "kulaks" under Stalinism greatly disrupted farm output in the 1920s and 1930s, contributing to the Soviet famine of 1932–33 (most especially the Holodomor in Ukraine).

However, Marxist–Leninist ideology did not allow for any substantial amount of market mechanism to coexist alongside central planning, so the private plot fraction of Soviet agriculture, which was its most productive, remained confined to a limited role.

Throughout its later decades the Soviet Union never stopped using substantial portions of the precious metals mined each year in Siberia to pay for grain imports, which has been taken by various authors as an economic indicator showing that the country's agriculture was never as successful as it ought to have been.

[citation needed] The real numbers, however, were treated as state secrets at the time, so accurate analysis of the sector's performance was limited outside the USSR and nearly impossible to assemble within its borders.

Despite immense land resources, extensive farm machinery and agrochemical industries, and a large rural workforce, Soviet agriculture was relatively unproductive.

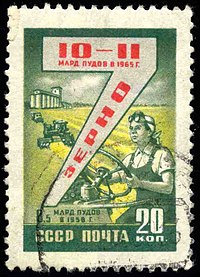

Organized on a large scale and relatively highly mechanized, its state and collective agriculture made the Soviet Union one of the world's leading producers of cereals, although bad harvests (as in 1972 and 1975) necessitated imports and slowed the economy.

Such performance showed that underlying potential was not lacking, which was not surprising as the agriculture in the Russian Empire was traditionally amongst the highest producing in the world, although rural social conditions since the October Revolution were hardly improved.

Leon Trotsky and the Opposition bloc had advocated a programme of industrialization which also proposed agricultural cooperatives and the formation of collective farms on a voluntary basis.

[2] Other scholars have argued that the economic programme of Trotsky differed from the forced policy of collectivisation implemented by Stalin after 1928 due to the levels of brutality associated with its enforcement.

Both grain production, and the number of farm animals rose above pre-civil war levels by early 1931, before major famine undermined these initially good results.

After the speech on collectivization that Stalin gave to the Communist Academy, there were no specific instructions on how exactly it had to be implemented, except for liquidation of kulaks as a class.

During the second five-year plan, under the policy of "cultural revolution" , the Soviet authorities established fines that were collected from farmers.

[9] Nikita Khrushchev was a top expert on agricultural policies and looked especially at collectivism, state farms, liquidation of machine-tractor stations, planning decentralization, economic incentives, increased labor and capital investment, new crops, and new production programs.

[16] Especially after his visit to the United States in 1959, he was keenly aware of the need to emulate and even match American superiority and agricultural technology.

[20] The Iowan visited the Soviet Union, where he became friends with Khrushchev, and Garst sold the USSR 5,000 short tons (4,500 t) of seed corn.

Garst warned the Soviets to grow the corn in the southern part of the country and to ensure there were sufficient stocks of fertilizer, insecticides, and herbicides.

[22] Khrushchev sought to abolish the Machine-Tractor Stations (MTS) which not only owned most large agricultural machines such as combines and tractors but also provided services such as plowing, and transfer their equipment and functions to the kolkhozes and sovkhozes (state farms).

Within three months, over half of the MTS facilities had been closed, and kolkhozes were being required to buy the equipment, with no discount given for older or dilapidated machines.

[24] In the 1940s Stalin put Trofim Lysenko in charge of agricultural research, with his crackpot ideas that flouted modern genetics science.

These goals were met by farmers who slaughtered their breeding herds and by purchasing meat at state stores, then reselling it back to the government, artificially increasing recorded production.

[31] In the new state and collective farms, outside directives failed to take local growing conditions into account, and peasants were often required to supply much of their produce for nominal payment.

The government tended to supply them with better machinery and fertilizers, not least because Soviet ideology held them to be a higher step on the scale of socialist transition.

However, most observers say that despite isolated successes,[37] collective farms and sovkhozes were inefficient, the agricultural sector being weak throughout the history of the Soviet Union.

[38] Hedrick Smith wrote in The Russians (1976) that, according to Soviet statistics, one fourth of the value of agricultural production in 1973 was produced on the private plots peasants were allowed (2% of the whole arable land).

[42] Statistics based on value rather than volume of production may give one view of reality, as public-sector food was heavily subsidized and sold at much lower prices than private-sector produce.

Another problem is these criticisms tend to discuss only a small number of consumer products and do not take into account the fact that the kolkhozy and sovkhozy produced mainly grain, cotton, flax, forage, seed, and other non-consumer goods with a relatively low value per unit area.

[42] He believes the above criticisms to be ideological and emphasizes "the possibility that socialized agriculture may be able to make valuable contributions to improving human welfare".

After the fall of Soviet Union, it has been recreated tongue-in-cheek in the albums and videos of the Moldovan group Zdob şi Zdub.