Nahda

[5] His political views, originally influenced by the conservative Islamic teachings of al-Azhar university, changed on a number of matters, and he came to advocate parliamentarism and women's education[citation needed].

After five years in France, he then returned to Egypt to implement the philosophy of reform he had developed there, summarizing his views in the book Takhlis al-Ibriz fi Talkhis Bariz (sometimes translated as The Quintessence of Paris), published in 1834.

Tahtawi's suggestion was that the Egypt and the Muslim world had much to learn from Europe, and he generally embraced Western society, but also held that reforms should be adapted to the values of Islamic culture.

Participating in an Arabic translation of the Bible in Great Britain that was published in 1857, Faris lived and worked there for 7 years, becoming a British citizen.

Faris continued to promote Arabic language and culture, resisting the 19th-century "Turkization" pushed by the Ottomans based in present-day Turkey.

After the bloody 1860 Druze–Maronite conflict and the increasing entrenchment of confessionalism, Al-Bustani founded the National School or Al-Madrasa Al-Wataniyya in 1863, on secular principles.

Nor is his advocacy of discriminatingly adopting Western knowledge and technology to "awaken" the Arabs' inherent ability for cultural success,(najah), unique among his generation.

That is, his writing articulates a specific formula for native progress that expresses a synthetic vision of the matrix of modernity within Ottoman Syria.

Syrian scholar, publicist, writer, poet and physician Francis Marrash (born between 1835 and 1837; died 1873 or 1874) had traveled throughout Western Asia and France in his youth.

He expressed ideas of political and social reforms in Ghabat al-haqq (first published c. 1865),[a] highlighting the need of the Arabs for two things above all: modern schools and patriotism "free from religious considerations".

[11] Marrash has been considered the first truly cosmopolitan Arab intellectual and writer of modern times, having adhered to and defended the principles of the French Revolution in his own works, implicitly criticizing Ottoman rule in Western Asia and North Africa.

The resentment towards Turkish rule fused with protests against the Sultan's autocracy, and the largely secular concepts of Arab nationalism rose as a cultural response to the Ottoman Caliphates claims of religious legitimacy.

Various Arab nationalist secret societies rose in the years prior to World War I, such as Al-fatat and the military based al-Ahd.

In the religious field, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani (1839–1897) gave Islam a modernist reinterpretation and fused adherence to the faith with an anti-colonial doctrine that preached Pan-Islamic solidarity in the face of European pressures.

He also favored the replacement of authoritarian monarchies with representative rule, and denounced what he perceived as the dogmatism, stagnation and corruption of the Islam of his age.

Al-Afghani's case for a redefinition of old interpretations of Islam, and his bold attacks on traditional religion, would become vastly influential with the fall of the Caliphate in 1924.

This created a void in the religious doctrine and social structure of Islamic communities which had been only temporarily reinstated by Abdul Hamid II in an effort to bolster universal Muslim support, suddenly vanished.

Applying the original message of the Islamic prophet Muhammad with no interference of tradition or the faulty interpretations of his followers, would automatically create the just society ordained by God in the Qur'an, and so empower the Muslim world to stand against colonization and injustices.

[15] Their status as an educated minority enabled them to significantly influence and contribute to the fields of literature, politics,[16] business,[16] philosophy,[17] music, theatre and cinema,[18] medicine,[19] and science.

[20] Damascus, Beirut, Cairo, and Aleppo were the main centers of the renaissance, which led to the establishment of schools, universities, theaters and printing presses there.

This awakening led to the emergence of a politically active movement known as the "association" that was accompanied by the birth of Arab nationalism and the demand for reformation in the Ottoman Empire.

[25] The Pen League was the first Arabic-language literary society in North America, formed initially by Syrians Nasib Arida and Abd al-Masih Haddad.

Members of the Pen League included: Kahlil Gibran, Elia Abu Madi, Mikhail Naimy, and Ameen Rihani.

[31] Shi'a scholars also contributed to the renaissance movement, including the linguist Ahmad Rida and his son-in-law the historian Muhammad Jaber Al Safa.

[citation needed] Many student missions from Egypt went to Europe in the early 19th century to study arts and sciences at European universities and acquire technical skills.

[3] A group of young writers formed Al-Madrasa al-Ḥadītha ('The New School'), and in 1925 began publishing the weekly literary journal Al-Fajr (The Dawn), which would have a great impact on Arabic literature.

[33] The most famous of these, Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931), challenged political and religious institutions with his writing,[citation needed] and was an active member of the Pen League in New York City from 1920 until his death.

The first printing press with Arabic letters was built in St John's monastery in Khinshara, Lebanon by "Al-Shamas Abdullah Zakher" in 1734.

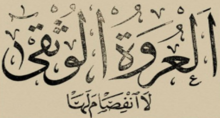

Muhammad Abduh and Jamāl al-Dīn al-Afghānī's weekly pan-Islamic anti-colonial revolutionary literary magazine Al-Urwah al-Wuthqa (The Firmest Bond)[39]—though it only ran from March to October 1884 and was banned by British authorities in Egypt and India[38]—was circulated widely from Morocco to India and it's considered one of the first and most important publications of the Nahda.