Al-Khwarizmi

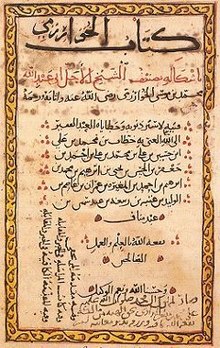

His popularizing treatise on algebra, compiled between 813–833 as Al-Jabr (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing),[6]: 171 presented the first systematic solution of linear and quadratic equations.

One of his achievements in algebra was his demonstration of how to solve quadratic equations by completing the square, for which he provided geometric justifications.

[17] Likewise, Al-Jabr, translated into Latin by the English scholar Robert of Chester in 1145, was used until the 16th century as the principal mathematical textbook of European universities.

[18][19][20][21] Al-Khwarizmi revised Geography, the 2nd-century Greek-language treatise by the Roman polymath Claudius Ptolemy, listing the longitudes and latitudes of cities and localities.

[32] Al-Tabari gives his name as Muḥammad ibn Musá al-Khwārizmī al-Majūsī al-Quṭrubbullī (محمد بن موسى الخوارزميّ المجوسـيّ القطربّـليّ).

However, Roshdi Rashed denies this:[34] There is no need to be an expert on the period or a philologist to see that al-Tabari's second citation should read "Muhammad ibn Mūsa al-Khwārizmī and al-Majūsi al-Qutrubbulli," and that there are two people (al-Khwārizmī and al-Majūsi al-Qutrubbulli) between whom the letter wa [Arabic 'و' for the conjunction 'and'] has been omitted in an early copy.

This would not be worth mentioning if a series of errors concerning the personality of al-Khwārizmī, occasionally even the origins of his knowledge, had not been made.

Toomer ... with naive confidence constructed an entire fantasy on the error which cannot be denied the merit of amusing the reader.On the other hand, David A.

His systematic approach to solving linear and quadratic equations led to algebra, a word derived from the title of his book on the subject, Al-Jabr.

When the work was translated into Latin in the 12th century as Algoritmi de numero Indorum (Al-Khwarizmi on the Hindu art of reckoning), the term "algorithm" was introduced to the Western world.

[23] He assisted a project to determine the circumference of the Earth and in making a world map for al-Ma'mun, the caliph, overseeing 70 geographers.

It was written with the encouragement of Caliph al-Ma'mun as a popular work on calculation and is replete with examples and applications to a range of problems in trade, surveying and legal inheritance.

Al-jabr is the process of removing negative units, roots and squares from the equation by adding the same quantity to each side.

For example, for one problem he writes, (from an 1831 translation) If some one says: "You divide ten into two parts: multiply the one by itself; it will be equal to the other taken eighty-one times."

[52]Victor J. Katz adds : The first true algebra text which is still extant is the work on al-jabr and al-muqabala by Mohammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi, written in Baghdad around 825.

[54]Roshdi Rashed and Angela Armstrong write: Al-Khwarizmi's text can be seen to be distinct not only from the Babylonian tablets, but also from Diophantus' Arithmetica.

It no longer concerns a series of problems to be solved, but an exposition which starts with primitive terms in which the combinations must give all possible prototypes for equations, which henceforward explicitly constitute the true object of study.

The Arabs in general loved a good clear argument from premise to conclusion, as well as systematic organization – respects in which neither Diophantus nor the Hindus excelled.

Called takht in Arabic (Latin: tabula), a board covered with a thin layer of dust or sand was employed for calculations, on which figures could be written with a stylus and easily erased and replaced when necessary.

Hitherto, Muslim astronomers had adopted a primarily research approach to the field, translating works of others and learning already discovered knowledge.

[71][72] Al-Khwārizmī's third major work is his Kitāb Ṣūrat al-Arḍ (Arabic: كتاب صورة الأرض, "Book of the Description of the Earth"),[73] also known as his Geography, which was finished in 833.

It is a major reworking of Ptolemy's second-century Geography, consisting of a list of 2402 coordinates of cities and other geographical features following a general introduction.

As Paul Gallez notes, this system allows the deduction of many latitudes and longitudes where the only extant document is in such a bad condition, as to make it practically illegible.

He transferred the points onto graph paper and connected them with straight lines, obtaining an approximation of the coastline as it was on the original map.

[79] Al-Khwārizmī wrote several other works including a treatise on the Hebrew calendar, titled Risāla fi istikhrāj ta'rīkh al-yahūd (Arabic: رسالة في إستخراج تأريخ اليهود, "Extraction of the Jewish Era").

It describes the Metonic cycle, a 19-year intercalation cycle; the rules for determining on what day of the week the first day of the month Tishrei shall fall; calculates the interval between the Anno Mundi or Jewish year and the Seleucid era; and gives rules for determining the mean longitude of the sun and the moon using the Hebrew calendar.

No direct manuscript survives; however, a copy had reached Nusaybin by the 11th century, where its metropolitan bishop, Mar Elias bar Shinaya, found it.

[81] Several Arabic manuscripts in Berlin, Istanbul, Tashkent, Cairo and Paris contain further material that surely or with some probability comes from al-Khwārizmī.

The Istanbul manuscript contains a paper on sundials; the Fihrist credits al-Khwārizmī with Kitāb ar-Rukhāma(t) (Arabic: كتاب الرخامة).