Alamosaurus

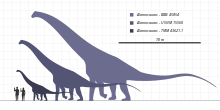

Isolated vertebrae and limb bones suggest that it could have reached sizes comparable to Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus, which would make it the absolute largest dinosaur known from North America.

Specimens of a juvenile Alamosaurus sanjuanensis have been recovered from only a few meters below the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary in Texas, making it among the last surviving non-avian dinosaur species.

Thomas Holtz proposed a maximum length of around 30 meters (98 ft) or more and an approximate weight of 72.5–80 tonnes (80–88 short tons) or more.

[2] Scott Hartman estimates Alamosaurus, based on a huge incomplete tibia that probably refers to it, being slightly shorter at 28–30 m (92–98 ft) and equal in weight to other massive titanosaurs, such as Argentinosaurus and Puertasaurus,[10] though he states that scientists do not know whether the massive tibia belongs to an Alamosaurus or a completely new species of sauropod.

[13] Venenosaurus also had depression-like fossae, but its "depressions" penetrated deeper into the vertebrae, were divided into two chambers, and extend farther into the vertebral columns.

Three articulated caudal vertebrae were collected above Hams Fork and are housed at the Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley.

The term saurus is derived from saura (σαυρα), the Greek word for "lizard", and is the most common suffix used in dinosaur names.

[15] In 1946, Gilmore posthumously described a more complete specimen, USNM 15660, found on June 15, 1937, on the North Horn Mountain of Utah by George B. Pearce.

[3] Some blocks catalogued under the same accession number as the relatively complete and well-known Alamosaurus specimen USNM 15660 and found in very close proximity to it based on bone impressions were first investigated by Michael Brett-Surman in 2009.

[4] The restored Alamosaurus skeletal mount at the Perot Museum (pictured right) was discovered when student Dana Biasatti, a member of an excavation team at a nearby site, went on a hike to search for more dinosaur bones in the area.

[19] A juvenile specimen of Alamosaurus has been reported to come from the Black Peaks Formation, which overlies the Javelina in Big Bend, Texas, and also straddles the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary.

The outcrop, situated in the middle strata of the formation about 90 meters (300 ft) below the K-Pg boundary and within the local range of Alamosaurus fossils, was dated to 69.0±0.9 million years old in 2010.

[24] Other scientists have also noted particular similarities with the saltasaurid Neuquensaurus and the Brazilian Trigonosaurus (the "Peiropolis titanosaur"), which is used in many cladistic and morphologic analyses of titanosaurians.

[3] A recent analysis published in 2016 by Anthony Fiorillo and Ron Tykoski indicates that Alamosaurus was a sister taxon to Lognkosauria and therefore to species such as Futalognkosaurus and Mendozasaurus, laying outside Saltasauridae (possibly being descended from close relations to the Saltasauridae), based on synapomorphies of cervical vertebral morphologies and two cladistic analyses.

The earliest fossils of Alamosaurus date to the Maastrichtian age, around 70 million years ago, and it rapidly became the dominant large herbivore of southern Laramidia.

[29][33] A second scenario, termed the "inland herbivore" scenario,[30] suggests that titanosaurs were present in North America throughout the Late Cretaceous and that their apparent absence reflects the relative rarity of fossil sites preserving the upland environments that titanosaurs favored, rather than their true absence from the continent.

[45] Contemporary archosaurs in the Ojo Alamo Formation include the potentially dubious oviraptorosaur Ojoraptorsaurus,[46] the dromaeosaurid Dineobellator,[47] the armored nodosaurid Glyptodontopelta,[48] and the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Ojoceratops.

[49] Non-archosaurian taxa that shared the same environment with Alamosaurus include various species of fish, rays, amphibians, lizards, turtles and multituberculates.