Alan Freed

His "role in breaking down racial barriers in U.S. pop culture in the 1950s, by leading white and black kids to listen to the same music, put the radio personality 'at the vanguard' and made him 'a really important figure'", according to the executive director.

Several sources suggest that he first discovered the term (as a euphemism for sexual intercourse) on the record "Sixty Minute Man" by Billy Ward and his Dominoes.

[12] Dubbed "The Old Knucklehead",[13] Freed had up to five hours of airtime every day on the station by June 1948:[14] the daytime Jukebox Serenade, the early-evening Wax Works and the nightly Request Review.

[15][16] Freed also had brief run-ins with management and was at one point temporarily fired for violating studio rules[17] and failing to show up for work for several days in a row.

Freed peppered his speech with hipster language, and, with a rhythm and blues record called "Moondog" as his theme song, broadcast R&B hits into the night.

[citation needed] Mintz proposed buying airtime on Cleveland radio station WJW (850 AM), which would be devoted entirely to R&B recordings, with Freed as host.

Soon, tapes of Freed's program, Moondog, began to air in the New York City area over station WNJR 1430 (now WNSW), in Newark, New Jersey.

[30] WINS eventually became an around-the-clock Top 40 rock and roll radio station, and would remain so until April 19, 1965, long after Freed left and three months after he had died—when it became an all-news outlet.

[33][34] Freed also worked at WABC (AM) starting in May 1958 but was fired from that station on November 21, 1959,[35] after refusing to sign a statement for the FCC that he had never accepted payola bribes.

[41][42] During this period, Freed was seen on other popular programs of the day, including To Tell the Truth, where he is seen defending the new "rock and roll" sound to the panelists, who were all clearly more comfortable with swing music: Polly Bergen, Ralph Bellamy, Hy Gardner and Kitty Carlisle.

Taking partial credit allowed him to receive part of a song's royalties, which he could help increase by heavily promoting the record on his own program.

In another example, however, Harvey Fuqua of The Moonglows insisted Freed's name was not merely a credit on the song "Sincerely" and that he did actually co-write it, although other band members disagreed.

[50] Because of the negative publicity from the payola scandal, no prestigious station would employ Freed, and he moved to the West Coast in 1960, where he worked at KDAY/1580 in Santa Monica, California.

[36] In 1962, after KDAY refused to allow him to promote "rock and roll" stage shows, Freed moved to WQAM in Miami, Florida, arriving in August 1962.

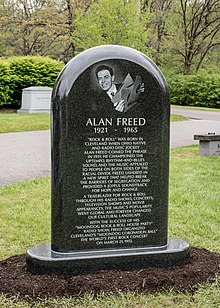

[53][54][55] Living in the Racquet Club Estates neighborhood of Palm Springs, California,[56] Freed died on January 20, 1965, from uremia and cirrhosis brought on by alcoholism, at the age of 43.

Prior to his death, the Internal Revenue Service had continued to maintain that he owed $38,000 for tax evasion, but Freed did not have the financial means to pay that amount.

The film starred Tim McIntire as Freed and included cameo appearances by Chuck Berry, Screamin' Jay Hawkins, Frankie Ford and Jerry Lee Lewis, performing in the recording studio and concert sequences.

The organization's website posted this note: "He became internationally known for promoting African-American rhythm and blues music on the radio in the United States and Europe under the name of rock and roll".

[62] In the early 1960s, Freed's career was destroyed by the payola scandal that hit the broadcasting industry, as well as by allegations of taking credit for songs he did not write[27] and by his chronic alcoholism.

In 1998, The Official Website of Alan Freed went online with the jumpstart from Brian Levant and Michael Ochs archives as well as a home page biography written by Ben Fong-Torres.

Freed was used as a character in Stephen King's short story "You Know They Got a Hell of a Band",[67] and was portrayed by Mitchell Butel in its television adaptation for the Nightmares & Dreamscapes mini-series.

[citation needed] He was the subject of a 1999 television movie, Mr. Rock 'n' Roll: The Alan Freed Story, starring Judd Nelson and directed by Andy Wolk.

[67] Other songs that reference Freed include "The King of Rock 'n Roll" by Terry Cashman and Tommy West, "Ballrooms of Mars" by Marc Bolan, "They Used to Call it Dope" by Public Enemy, "Payola Blues" by Neil Young, "Done Too Soon" by Neil Diamond, "The Ballad of Dick Clark" by Skip Battin, a member of the Byrds, and "This Is Not Goodbye, Just Goodnight" by Kill Your Idols.

The organization's Web page states that "despite his personal tragedies, Freed's innovations helped make rock and roll and the Top-40 format permanent fixtures of radio".

[71] The Wall Street Journal in 2015 recalled "Freed's sizable contributions to rock 'n' roll and to teenagers' more tolerant view of integration in the 1950s".

[72] One source said that "No man had as much influence on the coming culture of our society in such a short period of time as Alan Freed, the real King of Rock n Roll".

[73] Another source summarized his contribution as follows:[74] Alan Freed has secured a place in American music history as the first important rock 'n' roll disc jockey.

His ability to tap into and promote the emerging black musical styles of the 1950s to a white mainstream audience is seen as a vital step in rock's increasing dominance over American culture.The board of directors of the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame inducted Alan Freed into the class of 2017.