Albert Pierrepoint

[2] Henry had a series of jobs, including a butcher's apprentice, clog maker and a carrier in a local mill, but employment was mostly short-term.

[4] The role was part-time, with payment made only for individual hangings, rather than an annual stipend or salary, and there was no pension included with the position.

[6] Henry was removed from the list of executioners in July 1910 after arriving drunk at a prison the day before an execution and excessively berating his assistant.

"[27] In July 1940 Pierrepoint was the assistant at the execution of Udham Singh, an Indian revolutionary who had been convicted of shooting the colonial administrator Sir Michael O'Dwyer.

He and his assistant arrived the day before the execution, where he was told the height and weight of the prisoner; he viewed the condemned man through the "Judas hole" in the door to judge his build.

Pierrepoint secured the man's arms behind his back with a leather strap, and all five walked through a second door, which led to the execution chamber.

The metal eye through which the rope was looped was placed under the left jawbone which, when the prisoner dropped, forced the head back and broke the spine.

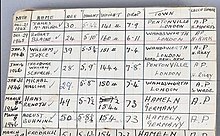

[34][35] During the Second World War Pierrepoint hanged 15 German spies, as well as US servicemen found guilty by courts martial of committing capital crimes in England.

When Pierrepoint entered the condemned man's cell for the hanging, Richter stood up, threw aside one of the guards and charged headfirst at the stone wall.

He did not tell her about his role of executioner until a few weeks after the nuptials when he was flown to Gibraltar to hang two saboteurs; on his return he explained the reason for his absence and she accepted it, saying that she had known about his second job all along, after hearing gossip locally.

He disliked any publicity connected to his role and was unhappy that his name had been announced to the press by Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery.

[46][47] The following day Pierrepoint hanged Theodore Schurch, a British soldier who had been found guilty under the Treachery Act 1940.

[49] In September 1946 Pierrepoint travelled to Graz, Austria, to train staff at Karlau Prison in the British form of long-drop hanging.

Previously, the Austrians had used a shorter drop, leaving the executed men to choke to death, rather than the faster long-drop kill.

[51][52] Despite Pierrepoint's expertise as an executioner and his experience with hanging the German war criminals at Hamelin, he was not selected as the hangman to carry out the sentences handed down at the Nuremberg trials; the job went to an American, Master Sergeant John C. Woods, who was relatively inexperienced.

Wilhelm Keitel took 20 minutes to die after the trapdoor opened; the trap was not wide enough, so some of the men hit the edges as they fell—more than one person's nose was torn off in the process—and others were strangled, rather than having their necks broken.

[52][53] After the war Pierrepoint left the delivery business and took over the lease of a pub, the Help the Poor Struggler on Manchester Road, in the Hollinwood area of Oldham.

[58] From the late 1940s and into the 1950s Pierrepoint, Britain's most experienced executioner, carried out several more hangings, including those of prisoners described by his biographer, Brian Bailey, as "the most notorious murderers of the period ... [and] three of the most controversial executions in the latter years of the death penalty.

In his autobiography, Pierrepoint considered the matter: As I polished the glasses, I thought if any man had a deterrent to murder poised before him, it was this troubadour whom I called Tish, coming to terms with his obsessions in the singing room of Help The Poor Struggler.

[63] In the months before he hanged Christie, Pierrepoint undertook another controversial execution, that of Derek Bentley, a 19-year-old man who had been an accomplice of Christopher Craig, a 16-year-old boy who shot and killed a policeman.

Ellis was in an abusive relationship with David Blakely, a racing driver; she shot him four times after what her biographer, Jane Dunn, called "three days of sleeplessness, panic, and pathological jealousy, fuelled by quantities of Pernod and a reckless consumption of tranquillizers".

The matter was discussed in Cabinet and a petition of 50,000 signatures was sent to the Home Secretary, Gwilym Lloyd George, to ask for a reprieve; he refused to grant one.

He wrote to the Prison Commissioners to point out that he had received a full fee in other cases of reprieve, and that he had spent additional money in employing bar staff.

The Commissioners advised he speak to the instructing sheriff, as it was his responsibility, not theirs; they also reminded him that his conditions of employment were that he was paid only for the execution, not in the case of a reprieve.

[74] The Home Office contacted the Sheriff of Lancashire, who paid Pierrepoint the full fee of £15 for his services, but he was adamant that he was still retiring.

[75][g] The Home Office considered prosecuting him under the Official Secrets Act 1939, but when two of the stories appeared that contained information that contradicted the recollections of other witnesses, they did not do so.

[79]In a 1976 interview with BBC Radio Merseyside, Pierrepoint expressed his uncertainty towards the sentiments, and said that when the autobiography was originally written, "there was not a lot of crime.

I do not think I will ever get over the shock of reading in his autobiography, many years ago, that like the Victorian executioner James Berry before him, he had turned against capital punishment and now believed that none of the executions he had carried out had achieved anything!

He did so in what Lizzie Seal, a reader in criminology, calls "quasi-religious language", including the phrase that a "higher power" selected him as an executioner.

[98][99] The following year the Murder (Abolition of Death Penalty) Act 1965 was passed, which imposed a five-year moratorium on executions.