Cervical vertebrae

In lizards and saurischian dinosaurs, the cervical ribs are large; in birds, they are small and completely fused to the vertebrae.

The most distinctive characteristic of this bone is the strong odontoid process (dens) that rises perpendicularly from the upper surface of the body and articulates with C1.

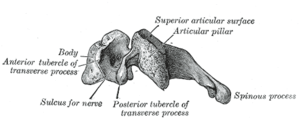

The transverse processes are of considerable size; their posterior roots are large and prominent, while the anterior are small and faintly marked.

The upper surface of each usually has a shallow sulcus for the eighth spinal nerve, and its extremity seldom presents more than a trace of bifurcation.

The transverse foramen may be as large as that in the other cervical vertebrae, but it is generally smaller on one or both sides; occasionally, it is double, and sometimes it is absent.

The movement of nodding the head takes place predominantly through flexion and extension at the atlanto-occipital joint between the atlas and the occipital bone.

However, the cervical spine is comparatively mobile, and some component of this movement is due to flexion and extension of the vertebral column itself.

This movement between the atlas and occipital bone is often referred to as the "yes joint", owing to its nature of being able to move the head in an up-and-down fashion.

[8] If it does occur, however, it may cause death or profound disability, including paralysis of the arms, legs, and diaphragm, which leads to respiratory failure.

This practice has come under review recently as incidence rates of unstable spinal trauma can be as low as 2% in immobilized patients.