Albert Seedman

Albert A. Seedman (August 9, 1918 – May 17, 2013) was an officer with the New York City Police Department (NYPD) for 30 years, known for solving several high-profile cases before resigning as chief of the Detective Bureau.

His tenure as chief of detectives of the city was short but memorable, marked by the Knapp Commission's corruption investigations which briefly cost him his job, several mob hits, and terror attacks carried out by the Black Liberation Army (BLA).

Frequently and accurately described as "cigar-chomping" and "tough-talking", with a personal style likened by a colleague to a Jewish gangster, he was one of the city's most visible police personnel during the 1960s and early 1970s.

After his retirement he wrote Chief!, a memoir of his time on the force and the high-profile cases he had been involved in, and appeared as a detective in the 1975 film Report to the Commissioner with Hector Elizondo and Tony King.

Seedman was born to a taxi driver and his wife, a sewing machine operator in the Garment District,[2] on Fox Street, near St. Mary's Park in the South Bronx[3] in 1918.

After studying French for a year,[2] he left the department to serve in Army intelligence and the military police in France and Belgium, including the Battle of the Bulge.

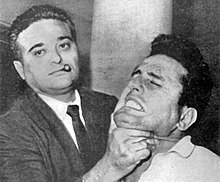

[5] The ensuing image of Dellernia's contorted face, "[stretched] ... as if it were pizza dough", as The New York Times put it in 1999,[5] while Seedman posed for the camera himself, sparked widespread public outcry.

The case had gained national attention when a story in the Times alleged that 38 neighbors had witnessed the crime in progress but did nothing about it, even as Genovese screamed for help repeatedly (an account that has since been disputed).

While driving on the Belt Parkway one summer morning near Plum Beach, a young woman named Nancy McEwen suddenly drifted off the road onto the median strip.

She died a short time later at Coney Island Hospital, where doctors found a small hole on the side of her head that turned out to have been caused by a bullet.

[9] On April 6, 1970, a townhouse on West 11th Street in Greenwich Village exploded in the early afternoon, damaging not only itself but several adjacent buildings, including the home of actor Dustin Hoffman and his wife.

Patrol officers were also permitted to investigate some lesser crimes on their own, such as assaults or car thefts; by 1972 they were already handling 70 percent of the reported burglary cases.

[12] The commission found evidence that in 1970, Seedman had accepted a free dinner worth $84.30 ($660 in current dollars[13]) from the New York Hilton Midtown, for himself, his wife and two guests.

Joseph Colombo Sr. was paralyzed from wounds inflicted by an assassin, himself killed seconds later, at an Italian Unity Day festival he had organized; although the department's investigation concluded the murder was not mob-related, Seedman continued to believe strongly that it had been, even though he admitted it would be difficult to prove.

[4] Ten months later, Joe Gallo, another member of the Colombo crime family, believed to have ordered the hit on his boss, was himself killed by gunmen at a Little Italy seafood restaurant.

[1] The greatest challenge to the department and its detectives during Seedman's tenure as chief of the bureau was another violent left-wing group, the Black Liberation Army (BLA).

An offshoot of the Black Panthers that espoused a more militant and radical philosophy, the BLA staged deadly ambushes on police officers in cities across the country.

[15] After the second attack, in January 1972, senior NYPD officials were wary of publicly attributing the killings to the BLA, or even acknowledging the group's existence.

Lindsay had changed his party affiliation from Republican to Democratic the previous year in order to seek the latter party's presidential nomination, and his aides told the police that publicly discussing the investigation of an African American terrorist group, one they considered largely an invention of disgruntled former Black Panthers, dedicated to killing police officers would conflict with the mayor's campaign themes; they also feared exacerbating racial tensions in the city.

In his news conference the day after the killings, Seedman downplayed notions that they were the work of the BLA although the police had received mail from them, taking credit and promising more.

Farrakhan and newly elected congressman Charles Rangel, who had come to the scene, warned them that the crowd outside, already throwing rocks, assaulting reporters present and attempting to damage police property, was beyond their control.

As Seedman walked back to his car, dodging bricks dropped from nearby roofs, he decided to retire,[19] ending his NYPD career two weeks later.

[20] At the time, he claimed his retirement was unrelated to the mosque incident; rather, he was attracting too much publicity and the department wanted to focus more on the uniformed patrol officers who made up the bulk of the ranks.

[21] Many of his colleagues believed the failure to fully investigate it resulted from senior police administrators' political cowardice; at his funeral, which uncharacteristically neither Commissioner Murphy nor Mayor Lindsay attended, Cardillo's commander angrily resigned from the department.

[16] An agreement was reached between the department and the mosque that designated it a "sensitive area", where police could not enter without their supervisors; this prevented the collection of ballistic evidence for two years.

With the tensions outside escalating, he had called Chief Inspector Michael Codd from the mosque and asked for two busloads of police cadets armed with nightsticks to keep order on the street outside.

He kept a replica of his gold "Chief of Detectives" shield to show people, and told the author of a 2006 book about Jewish police officers that he still carried his pearl-handled revolver "in case there is trouble.

"[1] In November 2012, Seedman posted on his Facebook page that French President François Hollande had named him a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in recognition of his military service there during World War II.

His own brother Harvey, a tough streetfighter in childhood, became a detective who served under Seedman, and his son Howard followed him into the force, an uncommon pattern in families of Jewish NYPD officers.

Barney "Cowboy" Rosenblatt, a detective in his novel Marilyn the Wild, carries a Colt revolver with his name and rank engraved near the trigger in a holster with small tassels, like Buffalo Bill.