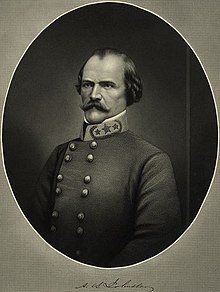

Albert Sidney Johnston

Considered by Confederate States President Jefferson Davis to be the finest general officer in the Confederacy before the later emergence of Robert E. Lee, he was killed early in the Civil War at the Battle of Shiloh on April 6, 1862.

He believed that the "safety of the republic depended upon the efficiency of the army... and upon the good discipline and subordination of the troops, which could only be secured by their obedience to their legal commander.

At the Battle of the Neches, Johnston and Vice President David G. Burnet were both cited in the commander's report "for active exertions on the field" and "having behaved in such a manner as reflects great credit upon themselves.

When the United States declared war on Mexico in May 1846, Johnston rode 400 miles from his home in Galveston to Port Isabel to volunteer for service in Brigadier General Zachary Taylor's Army of Occupation.

Such able graduates of West Point as Henry Clay, jun., and William R. McKee, were compelled to seek service through State appointments in volunteer regiments, while Albert Sidney Johnston, subsequently proved to be one of the ablest commanders ever sent from the Military Academy, could not obtain a commission from the General Government.

[3] Other subordinates in this unit included Earl Van Dorn, Edmund Kirby Smith, Nathan G. Evans, Innis N. Palmer, George Stoneman, R.W.

"[15] In March 1857, Brigadier General David E. Twiggs was appointed permanent commander of the department and Johnston returned to his position as colonel of the 2nd Cavalry.

Their objective was to install Alfred Cumming as governor of the Utah Territory, replacing Brigham Young, and restore U.S. legal authority in the region.

"[17] Even the Mormons commended Johnston's actions, with the Salt Lake City Deseret News reporting that "It takes a cool brain and good judgment to maintain a contented army and healthy camp through a stormy winter in the Wasatch Mountains.

In late June 1858, Johnston led the army through Salt Lake City without incident to establish Camp Floyd some 50 miles distant.

"[25] In 1856, he called abolitionism "fanatical, idolatrous, negro worshipping" in a letter to his son, fearing that the abolitionists would incite a slave revolt in the Southern states.

[26] Upon moving to California, Johnston sold one slave to his son and freed another, Randolph Hughes, or "Ran", who agreed to accompany the family on the condition of a $12/month contract for five more years of servitude.

[31] Early in the Civil War, Confederate President Jefferson Davis decided that the Confederacy would attempt to hold as much territory as possible, distributing military forces around its borders and coasts.

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant an excuse to take control of the strategically located town of Paducah, Kentucky, without raising the ire of most Kentuckians and the pro-U.S. majority in the State legislature.

[46] As the Confederate government concentrated efforts on the units in the East, they gave Johnston small numbers of reinforcements and minimal amounts of arms and material.

[62] Based on the assumption that Kentucky neutrality would act as a shield against a direct invasion from the north, circumstances that no longer applied in September 1861, Tennessee initially had sent men to Virginia and concentrated defenses in the Mississippi Valley.

[78][80][81] Johnston knew he could be trapped at Bowling Green if Fort Donelson fell, so he moved his force to Nashville, the capital of Tennessee and an increasingly important Confederate industrial center, beginning on February 11, 1862.

[92] Johnston, who had little choice in allowing Floyd and Pillow to take charge at Fort Donelson based on seniority after he ordered them to add their forces to the garrison, took the blame and suffered calls for his removal because a full explanation to the press and public would have exposed the weakness of the Confederate position.

[97][98][99] Johnston was in a perilous situation after the fall of Ft. Donelson and Henry; with barely 17,000 men to face an overwhelming concentration of Union force, he hastily fled south into Mississippi by way of Nashville and then into northern Alabama.

[104] Bragg at least calmed the nerves of Beauregard and Polk, who had become agitated by their apparent dire situation in the face of numerically superior forces, before Johnston's arrival on March 24, 1862.

It was not an easy undertaking; his army had been hastily thrown together, two-thirds of the soldiers had never fired a shot in battle, and drill, discipline, and staff work were so poor that the different divisions kept stumbling into each other on the march.

[110][111] Beauregard felt that this offensive was a mistake and could not possibly succeed, but Johnston replied "I would fight them if they were a million" as he drove his army on to Pittsburg Landing.

One of his famous moments in the battle occurred when he witnessed some of his soldiers breaking from the ranks to pillage and loot the U.S. camps and was outraged to see a young lieutenant among them.

Then, realizing he had embarrassed the man, he picked up a tin cup from a table and announced, "Let this be my share of the spoils today", before directing his army onward.

Harris and other staff officers removed Johnston from his horse, carried him to a small ravine near the "Hornets Nest", and desperately tried to aid the general, who had lost consciousness.

Johnston and his wounded horse, Fire Eater, were taken to his field headquarters on the Corinth road, where his body remained in his tent for the remainder of the battle.

He resumed leading the Confederate assault, which continued advancing and pushed the U.S. forces back to a final defensive line near the Tennessee river.

However, Grant was reinforced by 20,000 fresh troops from Don Carlos Buell's Army of the Ohio during the night and led a successful counter-attack the following day, driving the Confederates from the field and winning the battle.

His wife and five younger children, including one born after he went to war, chose to live out their days at home in Los Angeles with Eliza's brother, Dr. John Strother Griffin.

[126] Upon his passing, General Johnston received the highest praise ever given by the Confederate government: accounts were published on December 20, 1862, and after that, in the Los Angeles Star of his family's hometown.