Albrecht von Haller

At that university he graduated in May 1727, undertaking successfully in his thesis to prove that the so-called salivary duct, claimed as a recent discovery by Georg Daniel Coschwitz (1679–1729), was nothing more than a blood-vessel.

This poem of 490 hexameters is historically important as one of the earliest signs of the awakening appreciation of the mountains, though it is chiefly designed to contrast the simple and idyllic life of the inhabitants of the Alps with the corrupt and decadent existence of the dwellers in the plains.

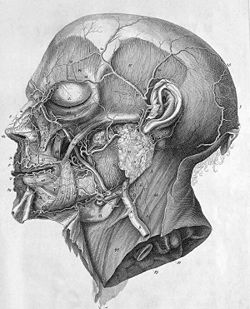

[4] In 1729 he returned to Bern and began to practice as a physician; his best energies, however, were devoted to the botanical and anatomical researches which rapidly gave him a European reputation, and procured for him from George II in 1736 a call to the chair of medicine, anatomy, botany and surgery in the newly founded University of Göttingen.

He also continued to persevere in his youthful habit of poetical composition, while at the same time he conducted a monthly journal (the Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen), to which he is said to have contributed twelve thousand articles relating to almost every branch of human knowledge.

[9] Notwithstanding all this variety of absorbing interests, Haller never felt at home in Göttingen; his untravelled heart kept on turning towards his native Bern, where he had been elected a member of the great council in 1745, and in 1753 he resolved to resign his chair and return to Switzerland.

[11] Haller was among the first botanists to realize the importance of herbaria to study variation in plants, and he therefore purposely included material from different localities, habitats and developmental phases.

[12] The twenty-one years of his life which followed were largely occupied in the discharge of his duties in the minor political post of a Rathausmann which he had obtained by lot, and in the preparation of his Bibliotheca medica, the botanical, surgical and anatomical parts of which he lived to complete; but he also found time to write the three philosophical romances Usong (1771), Alfred (1773) and Fabius and Cato (1774), in which his views as to the respective merits of despotism, of limited monarchy and of aristocratic republican government are fully set forth.

The quotation from Haller's Preface may be translated from the Latin as follows: "Of course, firstly the remedy must be proved on a healthy body, without being mixed with anything foreign; and when its odour and flavour have been ascertained, a tiny dose of it should be given and attention paid to all the changes of state that take place, what the pulse is, what heat there is, what sort of breathing and what exertions there are.

Then in relation to the form of the phenomena in a healthy person from those exposed to it, you should move on to trials on a sick body..." In his Science of Logic, Hegel mentions Haller's description of eternity, called by Kant "terrifying" in the Critique of Pure Reason (A613/B641).