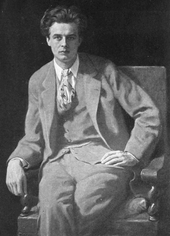

Aldous Huxley

[14][15] He was the third son of the writer and schoolmaster Leonard Huxley, who edited The Cornhill Magazine,[16] and his first wife, Julia Arnold, who founded Prior's Field School.

He taught French for a year at Eton College, where Eric Blair (who was to take the pen name George Orwell) and Steven Runciman were among his pupils.

Huxley completed his first (unpublished) novel at the age of 17 and began writing seriously in his early twenties, establishing himself as a successful writer and social satirist.

[28] During the First World War, Huxley spent much of his time at Garsington Manor near Oxford, home of Lady Ottoline Morrell, working as a farm labourer.

Heard was nearly five years older than Huxley, and introduced him to a variety of profound ideas, subtle interconnections, and various emerging spiritual and psychotherapy methods.

[32] Works of this period included novels about the dehumanising aspects of scientific progress, (his magnum opus Brave New World), and on pacifist themes (Eyeless in Gaza).

[33] In Brave New World, set in a dystopian London, Huxley portrays a society operating on the principles of mass production and Pavlovian conditioning.

Cyril Connolly wrote, of the two intellectuals (Huxley and Heard) in the late 1930s, "all European avenues had been exhausted in the search for a way forward – politics, art, science – pitching them both toward the US in 1937.

Not long afterwards, Huxley wrote his book on widely held spiritual values and ideas, The Perennial Philosophy, which discussed the teachings of renowned mystics of the world.

[51] In March 1938, Huxley's friend Anita Loos, a novelist and screenwriter, put him in touch with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), which hired him for Madame Curie which was originally to star Greta Garbo and be directed by George Cukor.

In his letter, he predicted: "Within the next generation I believe that the world's leaders will discover that infant conditioning and narcohypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging them and kicking them into obedience.

When Huxley refused to bear arms for the U.S. and would not state that his objections were based on religious ideals, the only excuse allowed under the McCarran Act, the judge had to adjourn the proceedings.

[58] As part of the MIT centennial program of events organised by the Department of Humanities, Huxley presented a series of lectures titled, "What a Piece of Work is a Man" which concerned history, language, and art.

[59] Robert S. de Ropp (scientist, humanitarian, and author), who had spent time with Huxley in England in the 1930s, connected with him again in the U.S. in the early 1960s and wrote that "the enormous intellect, the beautifully modulated voice, the gentle objectivity, all were unchanged.

"[60] Biographer Harold H. Watts wrote that Huxley's writings in the "final and extended period of his life" are "the work of a man who is meditating on the central problems of many modern men".

[64] In his last book, Literature and Science, Huxley wrote that "The ethical and philosophical implications of modern science are more Buddhist than Christian...."[65] In "A Philosopher's Visionary Prediction", published one month before he died, Huxley endorsed training in general semantics and "the nonverbal world of culturally uncontaminated consciousness", writing that "We must learn how to be mentally silent, we must cultivate the art of pure receptivity.... [T]he individual must learn to decondition himself, must be able to cut holes in the fence of verbalized symbols that hems him in.

This is the definition he gave, “…it is wrong for a man to say that he is certain of the objective truth of any proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty.”[67] Aldous Huxley's agnosticism, together with his speculative propensity, made it difficult for him fully embrace any form of institutionalised religion.

In the 1930s, Huxley and Gerald Heard both became active in the effort to avoid another world war, writing essays and eventually publicly speaking in support of the Peace Pledge Union.

But, they remained frustrated by the conflicting goals of the political left – some favoring pacifism (as did Huxley and Heard), while other wanting to take up arms against fascism in the Spanish Civil War.

[74] After joining the PPU, Huxley expressed his frustration with politics in a letter from 1935, “…the thing finally resolves itself into a religious problem — an uncomfortable fact which one must be prepared to face and which I have come during the last year to find it easier to face.”[75] Huxley and Heard turned their attention to addressing the big problems of the world through transforming the individual, "[...] a forest is only as green as the individual trees of the forest is green [...]"[73] This was the genesis of the Human Potential Movement, that gained traction in the 1960s.

"[78][79] In 1944, Huxley wrote the introduction to the Bhagavad Gita – The Song of God,[80] translated by Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood, which was published by the Vedanta Society of Southern California.

But the nature of this one Reality is such that it cannot be directly and immediately apprehended except by those who have chosen to fulfill certain conditions, making themselves loving, pure in heart, and poor in spirit.

In 1940, Huxley relocated from Hollywood to a 40-acre (16 ha) ranchito in the high desert hamlet of Llano, California, in northern Los Angeles County.

For example, some ten years after publication of The Art of Seeing, in 1952, Bennett Cerf was present when Huxley spoke at a Hollywood banquet, wearing no glasses and apparently reading his paper from the lectern without difficulty: Then suddenly he faltered—and the disturbing truth became obvious.

After revealing a letter she wrote to the Los Angeles Times disclaiming the label of Huxley as a "poor fellow who can hardly see" by Walter C. Alvarez, she tempered her statement: Although I feel it was an injustice to treat Aldous as though he were blind, it is true there were many indications of his impaired vision.

By an effort of the will, I can evoke a not very vivid image of what happened yesterday afternoon ...[95][96]Huxley married on 10 July 1919[97] Maria Nys (10 September 1899 – 12 February 1955), a Belgian epidemiologist from Bellem,[97] a village near Aalter, he met at Garsington, Oxfordshire, in 1919.

[99] Huxley was diagnosed with laryngeal cancer in 1960; in the years that followed, with his health deteriorating, he wrote the utopian novel Island,[100] and gave lectures on "Human Potentialities" both at the UCSF Medical Center and at the Esalen Institute.

The most substantial collection of Huxley's few remaining papers, following the destruction of most in the 1961 Bel Air Fire, is at the Library of the University of California, Los Angeles.

On 4 November 1963, less than three weeks before Huxley's death, author Christopher Isherwood, a friend of 25 years, visited in Cedars Sinai Hospital and wrote his impressions: I came away with the picture of a great noble vessel sinking quietly into the deep; many of its delicate marvelous mechanisms still in perfect order, all its lights still shining.

[104]At home on his deathbed, unable to speak owing to cancer that had metastasized, Huxley made a written request to his wife Laura for "LSD, 100 μg, intramuscular."