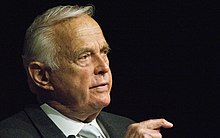

Alexander Butterfield

Alexander Porter Butterfield (born April 6, 1926) is a retired United States Air Force officer, public official, and businessman.

He revealed the White House taping system's existence on July 13, 1973, during the Watergate investigation but had no other involvement in the scandal.

[3] Butterfield enrolled in college at the University of California, Los Angeles,[1] where he became a friend of H. R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman.

[1][2][a] Initially, Butterfield was stationed at Las Vegas Air Force Base (now Nellis Air Force Base) as a fighter-gunnery instructor before being transferred to the 86th Fighter Wing in Munich, West Germany, in November 1951, where he was a member of the Skyblazers [ja] jet fighter acrobatic team.

[2] During the Vietnam War, Butterfield commanded a squadron of low and medium-level[5] combat tactical air reconnaissance aircraft.

[9][10] The two met in New York City about December 19, 1968, to discuss a role as a military aide, but when nothing suitable came up, Butterfield asked to take any job in the White House.

[12] Butterfield retired from the Air Force a few days later,[6][b] and his appointment as deputy assistant to the president was announced on January 23, 1969.

[11][18] Late in 1970, the president's aides lost confidence in Constance C. Stuart, Pat Nixon's staff director and press secretary, and Butterfield was assigned responsibility for overseeing the First Lady's events and publicity.

[19][20] The day after the 1972 presidential election, Pat Nixon confronted her husband over what she perceived to be Oval Office interference with her staff.

On February 10, 1971,[11] Haldeman's assistant, Lawrence Higby, told Butterfield that Nixon wanted a voice-activated audio taping system installed in the Oval Office and on White House telephones.

[26] John Dean testified in June 1973 that Nixon was deeply involved in the Watergate cover-up, and mentioned that he suspected White House conversations were taped.

[17] Senate Watergate Committee staff then asked the White House for a list of dates on which the President had met with Dean.

When committee Majority Investigator Scott Armstrong obtained the document, he realized it indicated the existence of a taping system.

[10] Then Sanders asked if there was any validity to John Dean's hypothesis that the White House had taped conversations in the Oval Office.

[37] All present recognized the significance of this disclosure, and, as former political adviser to President Gerald Ford James M. Cannon put it, "Watergate was transformed".

[41] Again breaking rules not to have private conversations or meetings with the White House, Thompson also informed Buzhardt about Butterfield's Friday night interview.

[42] Butterfield, scheduled to fly to Moscow on July 17 for a trade meeting, was worried that he would be called to testify before the Senate Watergate Committee and that this would force him to cancel his Russia trip.

Butterfield then called the White House and left a message for Special Counsel Leonard Garment (Dean's replacement), advising him of the content of his Friday testimony and the committee's subpoena for him to testify on Monday.

[f] Haig and Buzhardt[g] received Butterfield's message, and waited for Garment to return from a cross-country trip later that day.

[49] The New York Times called Butterfield's testimony "dramatic",[48] and historian William Doyle has noted that it "electrified Washington and triggered a constitutional crisis".

[50] Political scientist Keith W. Olson said Butterfield's testimony "fundamentally altered the entire Watergate investigation.

Haldeman retained $350,000 in cash in a locked briefcase in the office of Hugh W. Sloan Jr. at the Committee for the Re-Election of the President.

[55] On April 7,[56] Butterfield removed the cash and met a close friend at the Key Bridge Marriott in Rosslyn, Virginia.

The friend agreed to keep the cash in a safe deposit box in Arlington County, Virginia, and make it available to the White House on demand.

[55] Butterfield voluntarily revealed his role in "the 350" to United States Attorneys shortly after leaving the White House in March 1973.

Butterfield assigned former Nixon bodyguard Robert Newbrand as the spy in Kennedy's protective detail on September 8.

[59] By late 1972, Butterfield felt his job no longer challenged him, and he informally told President Nixon that he wanted to leave.

[64] In early January 1975, President Gerald Ford asked for the resignation of all executive branch officeholders who had been prominent in the Nixon administration.

Butterfield left the financial industry to start a business and productivity consulting firm, Armistead & Alexander.

[6][10] Butterfield retained an extensive number of records when he left the White House, some of them historically important, including the "zilch" memo, which helped form part of the basis for the book.