Alfred Wegener

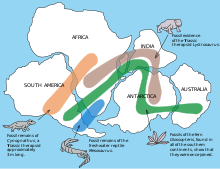

His hypothesis was not accepted by mainstream geology until the 1950s, when numerous discoveries such as palaeomagnetism provided strong support for continental drift, and thereby a substantial basis for today's model of plate tectonics.

[citation needed] Wegener studied physics, meteorology and astronomy at the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, completing two external semesters at Heidelberg and Innsbruck.

He completed his doctoral dissertation on the subject of applying the astronomical data of Alfonsine tables to contemporary computational methods in 1905 under the supervision of Julius Bauschinger and Wilhelm Förster.

The Denmark expedition was led by the Dane Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen and charged with studying the last unknown portion of the northeastern coast of Greenland.

Here Wegener also made his first acquaintance with death in a wilderness of ice when the expedition leader and two of his colleagues died on an exploratory trip undertaken with sled dogs.

His students and colleagues in Marburg particularly valued his ability to clearly and understandably explain even complex topics and current research findings without sacrificing precision.

His lectures formed the basis of what was to become a standard textbook in meteorology, first written In 1909/1910: Thermodynamik der Atmosphäre (Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere), in which he incorporated many of the results of the Greenland expedition.

On 6 January 1912 he presented his first proposal of continental drift in a lecture to the Geologische Vereinigung (Geological Association) at the Senckenberg Museum, Frankfurt am Main.

Only a few kilometres from the western Greenland settlement of Kangersuatsiaq the small team ran out of food while struggling to find their way through difficult glacial break-up terrain.

His brother Kurt remarked that Alfred Wegener's motivation was to "reestablish the connection between geophysics on the one hand and geography and geology on the other, which had become completely ruptured because of the specialized development of these branches of science."

In 1919, Wegener replaced Köppen as head of the Meteorological Department at the German Naval Observatory (Deutsche Seewarte) and moved to Hamburg with his wife and their two daughters.

[16] In 1922 the third, fully revised edition of "The Origin of Continents and Oceans" appeared, and discussion began on his theory of continental drift, first in the German language area and later internationally.

In November 1926 Wegener presented his continental drift theory at a symposium of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in New York City, again earning rejection from everyone but the chairman.

The 14 participants under his leadership were to establish three permanent stations from which the thickness of the Greenland ice sheet could be measured and year-round Arctic weather observations made.

Success depended on enough provisions being transferred from West camp to Eismitte ("mid-ice", also known as Central Station) for two men to winter there, and this was a factor in the decision that led to his death.

Owing to a late thaw, the expedition was six weeks behind schedule and, as summer ended, the men at Eismitte sent a message that they had insufficient fuel and so would return on 20 October.

On 24 September, although the route markers were by now largely buried under snow, Wegener set out with thirteen Greenlanders and his meteorologist Fritz Loewe to supply the camp by dog sled.

Expedition member Johannes Georgi estimated that there were only enough supplies for three at Eismitte, so Wegener and 27 year-old native Greenlander Rasmus Villumsen took two dog sleds and made for West camp.

But Wegener only published his idea after reading a paper in 1911 which criticised the prevalent hypothesis, that a bridge of land once connected Europe and America, on the grounds that this contradicts isostasy.

[22] Note prior advocates for various forms of continental dynamics: Abraham Ortelius, Antonio Snider-Pellegrini, Eduard Suess, Roberto Mantovani, Otto Ampferer, and Frank Bursley Taylor.

)[26] While his ideas attracted a few early supporters such as Alexander Du Toit from South Africa, Arthur Holmes in England [27] and Milutin Milanković in Serbia, for whom continental drift theory was the premise for investigating polar wandering,[28][29] the hypothesis was initially met with scepticism from geologists, who viewed Wegener as an outsider and were resistant to change.

[27] The German geologist Max Semper wrote a critique of the theory, which culminated in this mockery against Wegener:[30] "... so one can only ask for the necessary distance to be maintained and the request to stop honouring geology in the future, but to visit specialist areas that have so far forgotten to write above their gate: "Oh holy Saint Florian, spare this house, set others on fire!"

(Max Semper, 1917)Nevertheless, the eminent Swiss geologist Émile Argand advocated Wegener's theory in his inaugural address to the 1922 International Geological Congress.

[27] Charles Schuchert commented: During this vast time [of the split of Pangea] the sea waves have been continuously pounding against Africa and Brazil and in many places rivers have been bringing into the ocean great amounts of eroded material, yet everywhere the geographic shore lines are said to have remained practically unchanged!

[citation needed] Wegener was in the audience for this lecture, but made no attempt to defend his work, possibly because of an inadequate command of the English language.

[34] The 1960s saw several relevant developments in geology, notably the discoveries of seafloor spreading and Wadati–Benioff zones, and this led to the rapid resurrection of the continental drift hypothesis in the form of its direct descendant, the theory of plate tectonics.

Maps of the geomorphology of the ocean floors created by Marie Tharp in cooperation with Bruce Heezen were an important contribution to the paradigm shift that was starting.