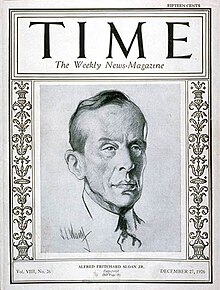

Alfred P. Sloan

[4] Like Henry Ford, the other "head man" of an automotive colossus, Sloan is remembered with a complex mixture of admiration for his accomplishments, appreciation for his philanthropy, and unease or reproach regarding his attitudes during the interwar period and World War II.

[11] These concepts, along with Ford's resistance to the change in the 1920s, propelled GM to industry-sales leadership by the early 1930s, a position it retained for over 70 years.

He preferred spying, investing in an internal undercover apparatus to gather information and monitor labor union activity.

The Alfred P. Sloan Museum, showcasing the evolution of the automobile industry and traveling galleries, is located in Flint, Michigan.

The foundation wanted to fund the production of a series of short films that would extol the virtues of capitalism and the American way of life.

[17] This resulted in the production of a series of animated cartoons by John Sutherland (producer) which were released on the 16mm non-theatrical market, and also distributed theatrically in 35mm by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

According to Edwin Black, Sloan was one of the central, behind-the-scenes 1934 founders of the American Liberty League, a political organization whose stated goal was to defend the Constitution, and who opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal.

[citation needed] Also according to Black, the GM chief continued to personally fund and organize fund-raising for the National Association of Manufacturers, which was critical of the New Deal.

[19] According to O'Toole (1995),[20] Sloan built a very objective organization, a company that paid significant attention to "policies, systems, and structures and not enough to people, principles, and values.

In the one personal element in the book, he makes passing reference to his wife: he abandons her on the first day of a European vacation to return to business in Detroit.

His language is as calculating as that of the engineer-of-old working with calipers and slide rule, as cold as the steel he caused to be bent to form cars: economizing, utility, facts, objectivity, systems, rationality, maximizing—that is the stuff of his vocabulary.

"[25] In 2005, Sloan's work at GM came under criticism for creating a complicated accounting system that prevents the implementation of lean manufacturing methods.

During this period, the auto industry experienced incredible growth as the public eagerly sought to purchase this life-changing utility known as the automobile.

In August 1938, a senior executive for General Motors, James D. Mooney, received the Grand Cross of the German Eagle for his distinguished service to the Reich.

"Nazi armaments chief Albert Speer told a congressional investigator that Germany could not have attempted its September 1939 blitzkrieg of Poland without the performance-boosting additive technology provided by Alfred P. Sloan and General Motors".

[5][29][30] During the war, GM's Opel Brandenburg facilities produced Ju 88 bombers, trucks, land mines and torpedo detonators for Nazi Germany.

[29] Charles Levinson, formerly deputy director of the European office of the CIO, alleged that Sloan remained on the board of Opel.

[32] According to Sloan, Opel was nationalized, along with most other industrial activity owned or co-owned by foreign interests, by the German state soon after the outbreak of war.

According to Sloan, GM in Detroit debated whether to even try to run Opel in the postwar era, or to leave to the interim West German government the question of who would pick up the pieces.

[32] Defending the German investment strategy as "highly profitable", Sloan told shareholders in 1939 that GM's continued industrial production for the Nazi government was merely sound business practice.

In a letter to a concerned shareholder, Sloan said that the manner in which the Nazi government ran Germany "should not be considered the business of the management of General Motors. ...

"[5] As the war drew to an end, most economists and New Deal policy makers assumed that without continued massive government spending, the pre-war Great Depression and its huge unemployment would return.

The economist Paul Samuelson warned that unless government took immediate action, "there would be ushered in the greatest period of unemployment and industrial dislocation which any economy has faced."

He pointed to workers' savings and pent-up demand, and predicted a huge jump in national income and a rise in standard of living.