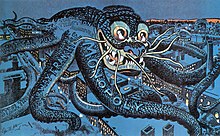

General Motors streetcar conspiracy

This suit created lingering suspicions that the defendants had in fact plotted to dismantle streetcar systems in many cities in the United States as an attempt to monopolize surface transportation.

The story as an urban legend has been written about by Martha Bianco, Scott Bottles, Sy Adler, Jonathan Richmond,[3] Cliff Slater,[4] and Robert Post.

Rail was more comfortable and had less rolling resistance than street traffic on granite block or macadam and horse-drawn streetcars were generally a step up from the horsebus.

Electric traction was faster, more sanitary, and cheaper to run; with the cost, excreta, epizootic risk, and carcass disposal of horses eliminated entirely.

[5] Early electric cars generally had a two-man crew, a holdover from horsecar days, which created financial problems in later years as salaries outpaced revenues.

In 1926, General Motors acquired a controlling share of the Yellow Coach Manufacturing Company and appointed Hertz as a main board director.

The new subsidiary made investments in small transit systems in Kalamazoo and Saginaw, Michigan, and in Springfield, Ohio, where they were successful in conversion to buses.

[20][full citation needed] In the 1941 film Citizen Kane, the lead character, who was loosely based on Hearst and Samuel Insull, complains about the influence of the '"traction interests".

[26] American City Lines (ACL), which had been organized to acquire local transportation systems in the larger metropolitan areas in various parts of the country in 1943, was merged with NCL in 1946.

[25] The federal government investigated some aspects of NCL's financial arrangements in 1941 (which calls into question the conspiracy myths' centrality of Quinby's 1946 letter).

[41] He also questioned who was behind the creation of the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, which had caused such difficulty for streetcar operations,[42] He was later to write a history of North Jersey Rapid Transit.

[49] Haugh was also president of the Key System, and later was involved in Metropolitan Coach Line's purchase of the passenger operations of the Pacific Electric Railway.

[54][full citation needed] During 1973, Bradford Snell, an attorney with Pillsbury, Madison and Sutro[55] and formerly, for a brief time, a scholar with the Brookings Institution, prepared a controversial and disputed paper titled "American ground transport: a proposal for restructuring the automobile, truck, bus, and rail industries.

[57] In it, Snell said that General Motors was "a sovereign economic state" and said that the company played a major role in the displacement of rail and bus transportation by buses and trucks.

[61] At the hearings in April 1974, San Francisco mayor and antitrust attorney Joseph Alioto testified that "General Motors and the automobile industry generally exhibit a kind of monopoly evil", adding that GM "has carried on a deliberate concerted action with the oil companies and tire companies...for the purpose of destroying a vital form of competition; namely, electric rapid transit".

)[citation needed] However, George Hilton, a professor of economics at UCLA and noted transit scholar[64][full citation needed] rejected Snell's view, stating, "I would argue that these [Snell's] interpretations are not correct, and, further, that they couldn't possibly be correct, because major conversions in society of this character—from rail to free wheel urban transportation, and from steam to diesel railroad propulsion—are the sort of conversions which could come about only as a result of public preferences, technological change, the relative abundance of natural resources, and other impersonal phenomena or influence, rather than the machinations of a monopolist.

[63][67] Quinby and Snell held that the destruction of streetcar systems was integral to a larger strategy to push the United States into automobile dependency.

Most transit scholars disagree, suggesting that transit system changes were brought about by other factors; economic, social, and political factors such as unrealistic capitalization, fixed fares during inflation, changes in paving and automotive technology, the Great Depression, antitrust action, the Public Utility Holding Company Act of 1935, labor unrest, market forces including declining industries' difficulty in attracting capital, rapidly increasing traffic congestion, the Good Roads Movement, urban sprawl, tax policies favoring private vehicle ownership, taxation of fixed infrastructure, consumerism, franchise repair costs for co-located property, wide diffusion of driving skills, automatic transmission buses, and general enthusiasm for the automobile.

[55] A significant rebuttal to Slater's article was published about one year later in the 1998 Transportation Quarterly finding that, without GM and other companies' efforts, the streetcar would not "have been driven to the verge of extinction by 1968".

Guy Span suggested that Snell and others fell into simplistic conspiracy theory thinking, bordering on paranoid delusions[69] stating, Clearly, GM waged a war on electric traction.

"[70]In 2010, CBS's Mark Henricks reported:[71] There is no question that a GM-controlled entity called National City Lines did buy a number of municipal trolley car systems.

It's also true that GM was convicted in a post-war trial of conspiring to monopolize the market for transportation equipment and supplies sold to local bus companies.