Algebraic geometry

Classically, it studies zeros of multivariate polynomials; the modern approach generalizes this in a few different aspects.

Algebraic geometry occupies a central place in modern mathematics and has multiple conceptual connections with such diverse fields as complex analysis, topology and number theory.

Wiles' proof of the longstanding conjecture called Fermat's Last Theorem is an example of the power of this approach.

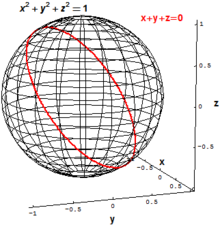

For instance, the two-dimensional sphere of radius 1 in three-dimensional Euclidean space R3 could be defined as the set of all points

For an algebraic set defined on the field of the complex numbers, the regular functions are smooth and even analytic.

Just as the formulas for the roots of second, third, and fourth degree polynomials suggest extending real numbers to the more algebraically complete setting of the complex numbers, many properties of algebraic varieties suggest extending affine space to a more geometrically complete projective space.

Real algebraic geometry also investigates, more broadly, semi-algebraic sets, which are the solutions of systems of polynomial inequalities.

A body of mathematical theory complementary to symbolic methods called numerical algebraic geometry has been developed over the last several decades.

This supports, for example, a model of floating point computation for solving problems of algebraic geometry.

CAD is an algorithm which was introduced in 1973 by G. Collins to implement with an acceptable complexity the Tarski–Seidenberg theorem on quantifier elimination over the real numbers.

Since 1973, most of the research on this subject is devoted either to improving CAD or finding alternative algorithms in special cases of general interest.

The basic general algorithms of computational geometry have a double exponential worst case complexity.

The language of schemes, stacks and generalizations has proved to be a valuable way of dealing with geometric concepts and became cornerstones of modern algebraic geometry.

Quillen model categories, Segal categories and quasicategories are some of the most often used tools to formalize this yielding the derived algebraic geometry, introduced by the school of Carlos Simpson, including Andre Hirschowitz, Bertrand Toën, Gabrielle Vezzosi, Michel Vaquié and others; and developed further by Jacob Lurie, Bertrand Toën, and Gabriele Vezzosi.

Another (noncommutative) version of derived algebraic geometry, using A-infinity categories has been developed from the early 1990s by Maxim Kontsevich and followers.

Some of the roots of algebraic geometry date back to the work of the Hellenistic Greeks from the 5th century BC.

The Delian problem, for instance, was to construct a length x so that the cube of side x contained the same volume as the rectangular box a2b for given sides a and b. Menaechmus (c. 350 BC) considered the problem geometrically by intersecting the pair of plane conics ay = x2 and xy = ab.

[2] In the 3rd century BC, Archimedes and Apollonius systematically studied additional problems on conic sections using coordinates.

The Persian mathematician Omar Khayyám (born 1048 AD) believed that there was a relationship between arithmetic, algebra and geometry.

[9][10][11] This was criticized by Jeffrey Oaks, who claims that the study of curves by means of equations originated with Descartes in the seventeenth century.

[12] Such techniques of applying geometrical constructions to algebraic problems were also adopted by a number of Renaissance mathematicians such as Gerolamo Cardano and Niccolò Fontana "Tartaglia" on their studies of the cubic equation.

[13] The French mathematicians Franciscus Vieta and later René Descartes and Pierre de Fermat revolutionized the conventional way of thinking about construction problems through the introduction of coordinate geometry.

Pascal and Desargues also studied curves, but from the purely geometrical point of view: the analog of the Greek ruler and compass construction.

Ultimately, the analytic geometry of Descartes and Fermat won out, for it supplied the 18th century mathematicians with concrete quantitative tools needed to study physical problems using the new calculus of Newton and Leibniz.

However, by the end of the 18th century, most of the algebraic character of coordinate geometry was subsumed by the calculus of infinitesimals of Lagrange and Euler.

It took the simultaneous 19th century developments of non-Euclidean geometry and Abelian integrals in order to bring the old algebraic ideas back into the geometrical fold.

The first of these new developments was seized up by Edmond Laguerre and Arthur Cayley, who attempted to ascertain the generalized metric properties of projective space.

One of the goals was to give a rigorous framework for proving the results of the Italian school of algebraic geometry.

Later, from about 1960, and largely led by Grothendieck, the idea of schemes was worked out, in conjunction with a very refined apparatus of homological techniques.

[15] Algebraic geometry now finds applications in statistics,[16] control theory,[17][18] robotics,[19] error-correcting codes,[20] phylogenetics[21] and geometric modelling.