Alhambra

[6] It contained most of the amenities of a Muslim city such as a Friday mosque, hammams (public baths), roads, houses, artisan workshops, a tannery, and a sophisticated water supply system.

Outside the Alhambra walls and located nearby to the east is the Generalife, a former Nasrid country estate and summer palace accompanied by historic orchards and modern landscaped gardens.

The first reference to al-Ḥamrāʼ came in lines of poetry attached to an arrow shot over the ramparts, recorded by Ibn Hayyan (d. 1076): "Deserted and roofless are the houses of our enemies; Invaded by the autumnal rains, traversed by impetuous winds; Let them within the red castle (Kalat al hamra) hold their mischievous councils; Perdition and woe surround them on every side.

When the Caliphate of Córdoba collapsed after 1009 and the Fitna (civil war) began, the Zirid leader Zawi ben Ziri established an independent kingdom for himself, the Taifa of Granada.

[32] With the Reconquista in full swing, the Christian kingdoms of Castile and Aragon – under kings Ferdinand III and James I, respectively – made major conquests across al-Andalus.

[33] Ibn al-Ahmar was a relatively new political player in the region and likely came from a modest background, but he was able to win the support and consent of multiple Muslim settlements under threat from the Castilian advance.

[37][38] The creation of the Sultan's Canal (Arabic: ساقلتة السلطان, romanized: Saqiyat al-Sultan), which brought water from the mountains to the east, solidified the identity of the Alhambra as a palace-city rather than a defensive and ascetic structure.

[41][12] The oldest major palace for which some remains have been preserved is the structure known as the Palacio del Partal Alto, in an elevated location near the centre of the complex, which probably dates from the reign of Ibn al-Ahmar's son, Muhammad II (r.

He also remodelled the Mexuar, created the highly decorated "Comares Façade" in the Patio del Cuarto Dorado, and redecorated the Court of the Myrtles, giving these areas much of their final appearance.

[65][75] Other artists and intellectuals, such as John Frederick Lewis, Richard Ford, François-René de Chateaubriand, and Owen Jones, helped make the Alhambra into an icon of the era with their writings and illustrations during the 19th century.

[86][87] The young architect "opened arcades that had been walled up, re-excavated filled-in pools, replaced missing tiles, completed inscriptions that lacked portions of their stuccoed lettering, and installed a ceiling in the still unfinished palace of Charles V".

[88] He also carried out systematic archaeological excavations in various parts of the Alhambra, unearthing lost Nasrid structures such as the Palacio del Partal Alto and the Palace of the Abencerrajes which provided deeper insight into the former palace-city as a whole.

[95] From the Puerta del Vino (Wine Gate) ran the Calle Real (Royal Street) dividing the Alhambra along its axial spine into a southern residential quarter, with mosques, hamams (bathhouses) and diverse functional establishments, and a greater northern portion, occupied by several palaces of the nobility with extensive landscaped gardens commanding views over the Albaicín.

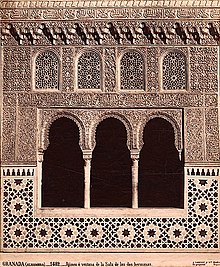

[98] The combination of carefully-proportioned courtyards, water features, gardens, arches on slender columns, and intricately-sculpted stucco and tile decoration gives Nasrid architecture qualities that are described as ethereal and intimate.

[99][100][101][102] Walls were built mostly in rammed earth, lime concrete, or brick and then covered with plaster, while wood (mostly pine) was used for roofs, ceilings, doors, and window shutters.

[99][104] The layout of the courtyards, the distribution of windows, and the use of water features were designed with the climate in mind, cooling and ventilating the environment in summer while minimizing cold drafts and maximizing sunlight in winter.

[123] The texts of the Alhambra include "devout, regal, votive, and Qur'anic phrases and sentences," formed into arabesques, carved into wood and marble, and glazed onto tiles.

[127][128] Most of the poetry is inscribed in Nasrid cursive script, while foliate and floral Kufic inscriptions—often formed into arches, columns, enjambments, and "architectural calligrams"—are generally used as decorative elements.

[161] On the north side of the Court of the Myrtles, inside the massive Comares Tower, is the Salón de los Embajadores ('Hall of the Ambassadors'), the largest room in the Alhambra.

[175][177][176][179] On the south side of the courtyard, the Sala de los Abencerrajes ('Hall of the Abencerrages') derives its name from a legend according to which the father of Boabdil, the last sultan of Granada, having invited the chiefs of that line to a banquet, massacred them here.

[191][192] Between 1539 and 1546 this upper floor was painted by Julio Aquiles and Alejandro Mayner with mythological scenes, depictions of Charles V's 1535 invasion of Tunis, and more formal classical-like motifs.

[199][200][201] The palace commissioned by Charles V in the middle of the Alhambra was designed by Pedro Machuca, an architect who had trained under Michelangelo in Rome and who was steeped in the culture of the Italian High Renaissance and of the artistic circles of Raphael and Giulio Romano.

[203][204] The construction of a monumental Italian-influenced palace in the heart of the Nasrid-built Alhambra symbolized Charles V's imperial status and the triumph of Christianity over Islam achieved by his grandparents (the Catholic Monarchs).

[205] Pedro Machuca had intended to create plazas with colonnades on the east and west sides of the building to serve as a grand new approach to the Alhambra palaces, but these were never executed.

Inside is a large Baroque altarpiece with gilded ornate columns completed in 1671, although the most impressive centrepiece of the altar, a sculpture of Our Lady of Sorrows (depicting Mary holding the body of Jesus), was carved between 1750 and 1760 by Torcuato Ruiz del Peral.

[232] During the Nasrid period there were several other country estates and palaces to the east of the Alhambra and the Generalife, located on the mountainside and taking advantage of the water supply system which ran through this area.

[36] A smaller branch known as the Acequia del Tercio also splits off from it several kilometres upstream and proceeded along higher ground before arriving at the top point of the Generalife's palace and gardens.

[36] From here it is channelled through the citadel via a complex system of conduits (acequias) and water tanks (albercones) which create the celebrated interplay of light, sound and surface in the palaces.

For example, several monuments constructed by the Saadian dynasty, which ruled Morocco in the 16th and 17th centuries, appear to imitate prototypes found in the Alhambra, particularly the Court of the Lions.

[247] After Owen Jones published Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details of the Alhambra in London from 1842 to 1845, a fanciful, ornamental, Alhambra-inspired Orientalist architectural style called Alhambresque became popular in the West in the 19th century.