Mesoamerican architecture

The distinctive features of Mesoamerican architecture encompass a number of different regional and historical styles, which however are significantly interrelated.

Iconographic decorations and texts on buildings are important contributors to the overall current knowledge of pre-Columbian Mesoamerican society, history and religion.

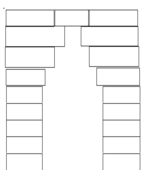

The following tables show the different phases of Mesoamerican architecture and archeology and correlates them with the cultures, cities, styles and specific buildings that are notable from each period.

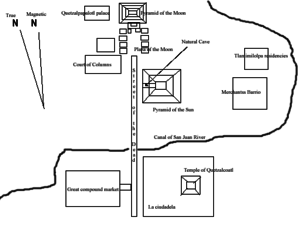

The southern part represented life, sustenance, and rebirth and often contained structures related to the continuity and daily function of the city-state, such as monuments depicting the noble lineages, or residential quarters, markets, etc.

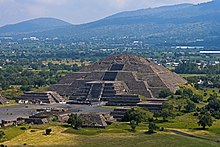

Some Mesoamericanists argue that in religious symbolism the Mesoamerican monumental architecture pyramids were mountains, stelae were trees, and wells, ballcourts and cenotes were caves that provided access to the underworld.

Some pyramids, temples, and other structures were designed to achieve special lighting effects on particular days important in the Mesoamerican cosmovision.

A famous example is the "El Castillo" pyramid at Chichen Itza, where a light-and-shadow effect can be observed during several weeks around the equinoxes.

[4] Vincent H Malmstrom has argued[5] that this is because of a general wish to align the pyramids to face the sunset on August 13, which was the beginning date of the Maya Long Count calendar.

However, recent research has shown that the earliest orientations marking sunsets on August 13 (and April 30) occur outside of the Maya area.

Their purpose must have been to record the dates separated by a period of 260 days (from August 13 to April 30), equivalent to the length of the sacred Mesoamerican calendrical count.

In general, the orientations in Mesoamerican architecture tend to mark the dates separated by multiples of 13 and 20 days, i.e. of basic periods of the calendrical system.

[12] While solar orientations prevail, some prominent buildings were aligned to Venus extremes,[13] a notable example being the Governor's Palace at Uxmal.

[14] Orientations to lunar standstill positions on the horizon have also been documented;[15] they are particularly common along the Northeast Coast of the Yucatán peninsula, where the worship of the goddess Ixchel, associated with the Moon, is known to have had an outstanding importance during the Postclassic period.

Mexican Archaeologist Eduardo Matos Moctezuma has shown that the symbolic and ritual life of this imperial shrine unified the patterns of forced tributary payments from hundreds of communities with the agricultural and hydraulic subsystems of food production.

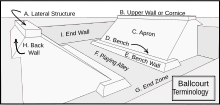

Over 1300 ball courts have been identified, and although there is a tremendous variation in size, they all have the same general shape: a long narrow alley flanked by two walls with horizontal, sloping, and sometimes vertical faces.

The later vertical faces, such as those at Chichen Itza and El Tajin, are often covered with complex iconography and scenes of human sacrifice.

At Copán, beneath over four-hundred years of later remodeling, a tomb for one of the ancient rulers has been discovered and the North Acropolis at Tikal appears to have been the site of numerous burials during the Terminal Pre-classic and Early Classic periods.

However, later improvements in quarrying techniques reduced the necessity for this limestone-stucco as their stones began to fit quite perfectly, yet it remained a crucial element in some post and lintel roofs.

Very large and ornate architectural ornaments were fashioned from a very enduring stucco (kalk), especially in the Maya region, where a type of hydraulic limestone cement or concrete was also used.

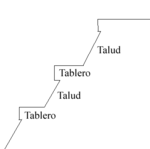

The upper partition is richly decorated with repeating geometric patterns and iconographic elements, especially the distinctive curved-nosed Chaac masks.

Moreover, unlike a corbelled arch, it does not rely on overlapping layers of blocks but cast-in-place concrete often supported by timber thrust beams.