Ibn al-Haytham

His most influential work is titled Kitāb al-Manāẓir (Arabic: كتاب المناظر, "Book of Optics"), written during 1011–1021, which survived in a Latin edition.

[13] The works of Alhazen were frequently cited during the scientific revolution by Isaac Newton, Johannes Kepler, Christiaan Huygens, and Galileo Galilei.

[16] He made major contributions to catoptrics and dioptrics by studying reflection, refraction and nature of images formed by light rays.

[23] Born in Basra, he spent most of his productive period in the Fatimid capital of Cairo and earned his living authoring various treatises and tutoring members of the nobilities.

[30] Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) was born c. 965 to a family of Arab[9][31][32][33][34] or Persian[35][36][37][38][39] origin in Basra, Iraq, which was at the time part of the Buyid emirate.

[40] He held a position with the title of vizier in his native Basra, and became famous for his knowledge of applied mathematics, as evidenced by his attempt to regulate the flooding of the Nile.

)[46]: Note 2 Among his students were Sorkhab (Sohrab), a Persian from Semnan, and Abu al-Wafa Mubashir ibn Fatek, an Egyptian prince.

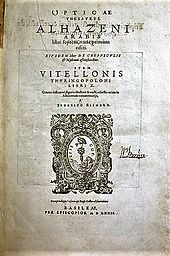

[50] It was printed by Friedrich Risner in 1572, with the title Opticae thesaurus: Alhazeni Arabis libri septem, nuncprimum editi; Eiusdem liber De Crepusculis et nubium ascensionibus (English: Treasury of Optics: seven books by the Arab Alhazen, first edition; by the same, on twilight and the height of clouds).

Ian P. Howard argued in a 1996 Perception article that Alhazen should be credited with many discoveries and theories previously attributed to Western Europeans writing centuries later.

But contrary to Howard, he explained why Ibn al-Haytham did not give the circular figure of the horopter and why, by reasoning experimentally, he was in fact closer to the discovery of Panum's fusional area than that of the Vieth-Müller circle.

Alhazen's most original contribution was that, after describing how he thought the eye was anatomically constructed, he went on to consider how this anatomy would behave functionally as an optical system.

[69] His understanding of pinhole projection from his experiments appears to have influenced his consideration of image inversion in the eye,[70] which he sought to avoid.

For example, to explain refraction from a rare to a dense medium, he used the mechanical analogy of an iron ball thrown at a thin slate covering a wide hole in a metal sheet.

Through works by Roger Bacon, John Pecham and Witelo based on Alhazen's explanation, the Moon illusion gradually came to be accepted as a psychological phenomenon, with the refraction theory being rejected in the 17th century.

The duty of the man who investigates the writings of scientists, if learning the truth is his goal, is to make himself an enemy of all that he reads, and ... attack it from every side.

He should also suspect himself as he performs his critical examination of it, so that he may avoid falling into either prejudice or leniency.An aspect associated with Alhazen's optical research is related to systemic and methodological reliance on experimentation (i'tibar)(Arabic: اختبار) and controlled testing in his scientific inquiries.

[111] Toomer concluded his review by saying that it would not be possible to assess Schramm's claim that Ibn al-Haytham was the true founder of modern physics without translating more of Alhazen's work and fully investigating his influence on later medieval writers.

Experiments with mirrors and the refractive interfaces between air, water, and glass cubes, hemispheres, and quarter-spheres provided the foundation for his theories on catoptrics.

[115]The book is a non-technical explanation of Ptolemy's Almagest, which was eventually translated into Hebrew and Latin in the 13th and 14th centuries and subsequently had an influence on astronomers such as Georg von Peuerbach[116] during the European Middle Ages and Renaissance.

[129] In elementary geometry, Alhazen attempted to solve the problem of squaring the circle using the area of lunes (crescent shapes), but later gave up on the impossible task.

[136][137][138][139] Ziauddin Sardar says that some of the greatest Muslim scientists, such as Ibn al-Haytham and Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī, who were pioneers of the scientific method, were themselves followers of the Ashʿari school of Islamic theology.

[141] Alhazen wrote a work on Islamic theology in which he discussed prophethood and developed a system of philosophical criteria to discern its false claimants in his time.

[147] In al-Andalus, it was used by the eleventh-century prince of the Banu Hud dynasty of Zaragossa and author of an important mathematical text, al-Mu'taman ibn Hūd.

[148] This translation was read by and greatly influenced a number of scholars in Christian Europe including: Roger Bacon,[149] Robert Grosseteste,[150] Witelo, Giambattista della Porta,[151] Leonardo da Vinci,[152] Galileo Galilei,[153] Christiaan Huygens,[154] René Descartes,[155] and Johannes Kepler.

If, therefore, we confine our interest only to the history of physics, there is a long period of over twelve hundred years during which the Golden Age of Greece gave way to the era of Muslim Scholasticism, and the experimental spirit of the noblest physicist of Antiquity lived again in the Arab Scholar from Basra.

[162] In 2014, the "Hiding in the Light" episode of Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson, focused on the accomplishments of Ibn al-Haytham.

Over forty years previously, Jacob Bronowski presented Alhazen's work in a similar television documentary (and the corresponding book), The Ascent of Man.

In episode 5 (The Music of the Spheres), Bronowski remarked that in his view, Alhazen was "the one really original scientific mind that Arab culture produced", whose theory of optics was not improved on till the time of Newton and Leibniz.

UNESCO declared 2015 the International Year of Light and its Director-General Irina Bokova dubbed Ibn al-Haytham 'the father of optics'.

An international campaign, created by the 1001 Inventions organisation, titled 1001 Inventions and the World of Ibn Al-Haytham featuring a series of interactive exhibits, workshops and live shows about his work, partnering with science centers, science festivals, museums, and educational institutions, as well as digital and social media platforms.