Alice Freeman Palmer

As Alice Freeman, she was president of Wellesley College from 1881 to 1887, when she left to marry the Harvard professor George Herbert Palmer.

[8] After his return, when she was six-years old, the family moved into a rented house in Windsor, New York[9] and her father established a medical practice in the town.

[8] She met Thomas Barclay, a student at Yale University, in her hometown when he worked as a teacher to pay off his college expenses.

She was inspired by a lecture given by Anna Elizabeth Dickinson and engaged in community service, giving away some of her savings for college, at a time when she did not have a winter coat.

She became a member of the Presbyterian Church in her final year at the academy, both because it was an expected action and as an expression of her personal commitment.

[11] Biographer Ruth Birgitta Anderson Bordin suggests that Palmer was influenced to gain a college education due to her relationship with Barclay, having been inspired by orator Anna Dickinson, and having experienced the financial uncertainty of her family.

Therefore, they agree to help with the financing with the stipulation that Palmer provide financial support so that her brother and perhaps other siblings could go to college.

Her father declared bankruptcy in 1877[17] and Alice assumed his debts and moved the family to Saginaw to a rented house that was paid for with her principal's salary and the income that her mother made from boarders.

[2][19] Palmer "transformed the fledgling school from one devoted to Christian domesticity into one of the nation's premier colleges for women.

[21] She labored earnestly in many paths to increase opportunities of service for college women, and in every field to choose for advancement those with capacity for leadership and scholarship, who should themselves become creators of new and larger opportunities for others.In 1881, Palmer co-founded the Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which later became the American Association of University Women.

[22] In 1892, Palmer accepted an offer by the president of the new University of Chicago as non-resident dean of the women's department[2][26][21] or the colleges and graduate schools.

[19] During her time as dean of the women's department she doubled the percentage of the female students at the school from 24% to 48%, which resulted in a backlash from mainly male faculty members.

[21] During her time at Wellesley she met her future husband, George Herbert Palmer, who taught at Harvard University.

She was engaged to marry George and resigned from her position at Wellesley College in June 1887[2] partly due to her poor health.

They both pursued their individual careers, and George contributed efforts to managing the household, particularly when she was at the University of Illinois during her post there.

[21] While summering at her husband's home in Boxford, Massachusetts, she explored the local area, sewed, watched birds, and took up photography.

[25] They took long trips to Europe over three of George's sabbaticals, during which they lived in their favorite cities and traveled through the countryside on bicycles.

[29] In December 1902, while the Palmers were in Paris on sabbatical, she complained of pains that required surgery to remove a bowel obstruction.

[25] Her life was commemorated at a service at Harvard University in 1903 attended by college presidents whom she had known as well as other notable individuals in academia.

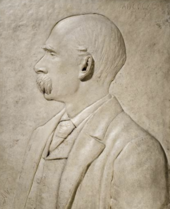

[30] Her widower, George, retained her ashes until 1909, when a monument was erected by sculptor Daniel Chester French at Houghton Chapel in Wellesley College.

[33] In 1908, the first endowment at the AAUW was created in Palmer's memory to help women attend colleges, conduct research, and write dissertations.

The college had as its mission to create a female literary society, with the hope of bringing such groups back to Whittier College after they faded from existence at the beginning of World War I. Fullerton Junior College transfer Jessamynn West and friends reportedly researched and lobbied extensively to name the group for Alice Freeman Palmer, due to her reputation as a staunch advocate of higher education for women during the late 19th century.

In World War II, the United States liberty ship SS Alice F. Palmer was named in her honor.