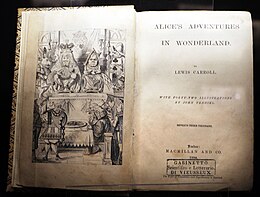

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

It details the story of a girl named Alice who falls through a rabbit hole into a fantasy world of anthropomorphic creatures.

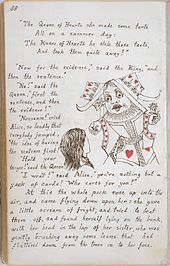

The girls and Carroll took another boat trip a month later, when he elaborated the plot of the story to Alice, and in November, he began working on the manuscript in earnest.

He subsequently approached John Tenniel to reinterpret his visions through his own artistic eye, telling him that the story had been well-liked by the children.

[23] Alice, a young girl, sits bored by a riverbank and spots a White Rabbit with a pocket watch and waistcoat lamenting that he is late.

Unhappy, Alice bursts into tears, and the passing White Rabbit flees in a panic, dropping a fan and two gloves.

Attempting to extract her, the White Rabbit and his neighbours eventually take to hurling pebbles that turn into small cakes.

During the Caterpillar's questioning, Alice begins to admit to her current identity crisis, compounded by her inability to remember a poem.

She takes the key and uses it to open the door to the garden, which turns out to be the croquet court of the Queen of Hearts, whose guard consists of living playing cards.

The Mock Turtle sings them "Beautiful Soup", during which the Gryphon drags Alice away for a trial, in which the Knave of Hearts stands accused of stealing the Queen's tarts.

[32] The Mock Turtle speaks of a drawling-master, "an old conger eel", who came once a week to teach "Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils".

This is a reference to the art critic John Ruskin, who came once a week to the Liddell house to teach the children to draw, sketch, and paint in oils.

[45] According to Gillian Beer, Carroll's play with language evokes the feeling of words for new readers: they "still have insecure edges and a nimbus of nonsense blurs the sharp focus of terms".

[51][52] Literary scholar Melanie Bayley asserts in the New Scientist magazine that Carroll wrote Alice in Wonderland in its final form as a satire on mid-19th century mathematics.

[55] Nina Auerbach discusses how the novel revolves around eating and drinking which "motivates much of her [Alice's] behaviour", for the story is essentially about things "entering and leaving her mouth.

[61] Unlike the creatures of Wonderland, who approach their world's wonders uncritically, Alice continues to look for rules as the story progresses.

Alice has provided a challenge for other illustrators, including those of 1907 by Charles Pears and the full series of colour plates and line-drawings by Harry Rountree published in the (inter-War) Children's Press (Glasgow) edition.

Other significant illustrators include: Arthur Rackham (1907), Willy Pogany (1929), Mervyn Peake (1946), Ralph Steadman (1967), Salvador Dalí (1969), Graham Overden (1969), Max Ernst (1970), Peter Blake (1970), Tove Jansson (1977), Anthony Browne (1988), Helen Oxenbury (1999),[66] and Lisbeth Zwerger (1999).

[77][78] The text blocks of the original edition were removed from the binding and sold with Carroll's permission to the New York publishing house of D. Appleton & Company.

[101] In the late 19th century, Walter Besant wrote that Alice in Wonderland "was a book of that extremely rare kind which will belong to all the generations to come until the language becomes obsolete".

It helped to replace stiff Victorian didacticism with a looser, sillier, nonsense style that reverberated through the works of language-loving 20th-century authors as different as James Joyce, Douglas Adams and Dr.

[111][112] The first full major production was Alice in Wonderland, a musical play in London's West End by Henry Savile Clarke and Walter Slaughter, which premiered at the Prince of Wales Theatre in 1886.

[114] The musical was frequently revived during West End Christmas seasons during the four decades after its premiere, including a London production at the Globe Theatre in 1888, with Isa Bowman as Alice.

[115][116] As the book and its sequel are Carroll's most widely recognised works, they have also inspired numerous live performances, including plays, operas, ballets, and traditional English pantomimes.

[118] A dramatisation by Herbert M. Prentice premiered at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon in 1947, and was in turn adapted for television by John Glyn-Jones and shown by the BBC on Christmas Day 1948.

Performed on a bare stage with the actors in modern dress, the play is a loose adaptation, with song styles ranging the globe.

[122][123] Although the original production in Hamburg, Germany, received only a small audience, Tom Waits released the songs as the album Alice in 2002.

[131] In 2022, the Opéra national du Rhin performed the ballet Alice, with a score by Philip Glass, in Mulhouse, France.

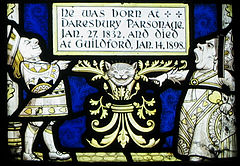

[132] Characters from the book are depicted in the stained glass windows of Carroll's hometown church, All Saints', in Daresbury, Cheshire, England.

[133] Another commemoration of Carroll's work in his home county of Cheshire is the granite sculpture The Mad Hatter's Tea Party, located in Warrington.

[135][136] In 2015, Alice characters were featured on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the Royal Mail to mark the 150th anniversary of the publication of the book.