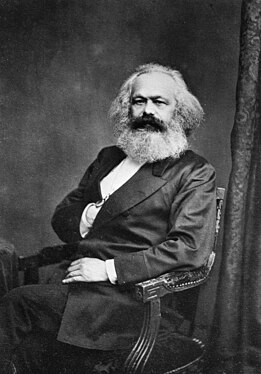

Marx's theory of alienation

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the separation and estrangement of people from their work, their wider world, their human nature, and their selves.

Alienation is a consequence of the division of labour in a capitalist society, wherein a human being's life is lived as a mechanistic part of a social class.

[2] Marx's theory draws heavily from Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, and from The Essence of Christianity (1841) by Ludwig Feuerbach.

[8] Marx derives this concept from Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whom he credits with significant insight into the basic structure of the modern social world, and how it is disfigured by alienation.

Hegel believes that the family, civil society, and the political state facilitate people's actualization, both as individuals and members of a community.

[10] Marx shares Hegel's belief that subjective alienation is widespread, but denies that the modern state enables individuals to actualize themselves.

The distribution of private property in the hands of wealth owners, combined with government enforced taxes compel workers to labour.

The worker "[d]oes not feel content but unhappy, does not develop freely his physical and mental energy but mortifies his body and ruins his mind.

The Gattungswesen ('species-being' or 'human nature'), of individuals is not discrete (separate and apart) from their activity as a worker and as such species-essence also comprises all of innate human potential as a person.

Conceptually, in the term species-essence, the word species describes the intrinsic human mental essence that is characterised by a "plurality of interests" and "psychological dynamism," whereby every individual has the desire and the tendency to engage in the many activities that promote mutual human survival and psychological well-being, by means of emotional connections with other people, with society.

In the course of economic development when a new type of economy displaced an old type of economy—agrarian feudalism superseded by mercantilism, in turn superseded by the Industrial Revolution—the rearranged economic order of the social classes favoured the social class who controlled the technologies (the means of production) that made possible the change in the relations of production.

In the classless, collectively-managed communist society, the exchange of value between the objectified productive labour of one worker and the consumption benefit derived from that production will not be determined by or directed to the narrow interests of a bourgeois capitalist class, but instead will be directed to meet the needs of each producer and consumer.

Capitalism reduces the labour of the worker to a commercial commodity that can be traded in the competitive labour-market, rather than as a constructive socio-economic activity that is part of the collective common effort performed for personal survival and the betterment of society.

In a capitalist economy, the businesses who own the means of production establish a competitive labour-market meant to extract from the worker as much labour (value) as possible in the form of capital.

The capitalist economy's arrangement of the relations of production provokes social conflict by pitting worker against worker in a competition for "higher wages", thereby alienating them from their mutual economic interests; the effect is a false consciousness, which is a form of ideological control exercised by the capitalist bourgeoisie through its cultural hegemony.

[19] In The Phenomenology of Spirit (1807), Hegel described the stages in the development of the human Geist ('spirit'), by which men and women progress from ignorance to knowledge of the self and of the world.

[20] In these works, Feuerbach argues that an inappropriate separation of individuals from their essential human nature is at the heart of Christianity.

[23]That humans psychologically require the life activities that lead to their self-actualisation as persons remains a consideration of secondary historical relevance because the capitalist mode of production eventually will exploit and impoverish the proletariat until compelling them to social revolution for survival.

In The Marxist-Humanist Theory of State-Capitalism (1992), Raya Dunayevskaya discusses and describes the existence of the desire for self-activity and self-actualisation among wage-labour workers struggling to achieve the elementary goals of material life in a capitalist economy.

But the former class feels at ease and strengthened in this self-estrangement, it recognises estrangement as its own power, and has in it the semblance of a human existence.

[24]In discussion of "aleatory materialism" (matérialisme aléatoire) or "materialism of the encounter," French philosopher Louis Althusser criticised a teleological (goal-oriented) interpretation of Marx's theory of alienation because it rendered the proletariat as the subject of history; an interpretation tainted with the absolute idealism of the "philosophy of the subject," which he criticised as the "bourgeois ideology of philosophy".