Idealism

[7]A more recent definition by Willem deVries sees idealism as "roughly, the genus comprises theories that attribute ontological priority to the mental, especially the conceptual or ideational, over the non-mental.

[25] According to scholars like Nathaniel Alfred Boll and Ludwig Noiré, with Plotinus, a true idealism which holds that only soul or mind exists appears for the first time in Western philosophy.

[36] Later Western theistic idealism such as that of Hermann Lotze offers a theory of the "world ground" in which all things find their unity: it has been widely accepted by Protestant theologians.

[41][42] The Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad also describes brahman as awaress and bliss, and states that "this great being (mahad bhūtam) without an end, boundless (apāra), [is] nothing but vijñāna [consciousness].

[59][58] Some writers like philosopher Jay Garfield and German philologist Lambert Schmithausen argue that Indian Yogacarins are metaphysical idealists that reject the existence of a mind independent external world.

[59] However, a major difference here is that while Kant holds that the thing-in-itself is unknowable, Indian Yogacarins held that ultimate reality is knowable, but only through the non-conceptual yogic perception of a highly trained meditative mind.

[59] Other scholars like Dan Lusthaus and Thomas Kochumuttom see Yogācāra as a kind of phenomenology of experience which seeks to understand how suffering (dukkha) arises in the mind, not provide a metaphysics.

[58] Vasubandhu also responds against three objections to idealism which indicate his view that all appearances are caused by mind: (1) the issue of spatio-temporal continuity, (2) accounting for intersubjectivity, and (3) the causal efficacy of matter on subjects.

To do this, he relies on the Indian "Principle of Lightness" (an appeal to parsimony like Occam's Razor) and argues that idealism is the "lighter" theory since it posits a smaller number of entities.

[74] Many Chinese Buddhist traditions like Huayan, Zen, and Tiantai were also strongly influenced by an important text called the Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna, which synthesized consciousness-only idealism with buddha-nature thought.

[86] According to Wang, the ultimate principle or pattern (lǐ) of the whole universe is identical with the mind, which forms one body or substance (yì tǐ) with "Heaven, Earth, and the myriad creatures" of the world.

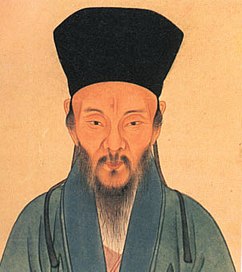

[87] Yogācāra idealism saw a revival in the 20th century, associated figures like Yang Wenhui (1837–1911), Taixu, Liang Shuming, Ouyang Jingwu (1870–1943), Wang Xiaoxu (1875–1948), and Lu Cheng.

Malebranche argued that Platonic ideas (which exist only in the mind of God) are the ultimate ground of our experiences and of the physical world, a view that prefigures later idealist positions.

[98] A similar idealistic philosophy was developed at around the same time as Berkeley by Anglican priest and philosopher Arthur Collier (Clavis Universalis: Or, A New Inquiry after Truth, Being a Demonstration of the Non-Existence, or Impossibility, of an External World, 1713).

Critics of subjective idealism include Bertrand Russell's popular 1912 book The Problems of Philosophy, Australian philosopher David Stove,[103] Alan Musgrave,[104] and John Searle.

[108] Kant's system also affirms the reality of a free truly existent self and of a God, which he sees as being possible because the non-temporal nature of the thing-in-itself allows for a radical freedom and genuine spontaneity.

[108] Kant's main argument for his idealism, found throughout the Critique of Pure Reason, is based on the key premise that we always represent objects in space and time through our a priori intuitions (knowledge which is independent from any experience).

[109] Thus, according to Kant, space and time can never represent any "property at all of any things in themselves nor any relations of them to each other, i.e., no determination of them that attaches to objects themselves and that would remain even if one were to abstract from all subjective conditions of intuition" (CPuR A 26/B 42).

[115][116] A key concern of the Neo-Kantians was to update Kantian epistemology, particularly in order to provide an epistemic basis for the modern sciences (all while avoiding ontology altogether, whether idealist or materialist).

"[114] Hence, Cassirer defended an epistemic worldview that held that one cannot reduce reality to any independent or substantial object (physical or mental), instead, there are only different ways of describing and organizing experience.

[140] In manifesting the entire world, the absolute enacts a process of self-actualization through a grand structure or master logic, which is what Hegel calls "reason" (Vernunft), and which he understands as a teleological reality.

[143] Schopenhauer maintains Kant's idealist epistemology which sees even space, time and causality are mere mental representations (vorstellungen) conditioned by the subjective mind.

However, he replaces Kant's unknowable thing-in-itself with an absolute reality underlying all ideas that is a single irrational Will, a view that he saw as directly opposed to Hegel's rational Spirit.

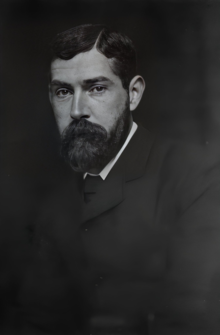

[153] Key figures of this transatlantic movement include many of the British idealists, such as T. H. Green (1836–1882), F. H. Bradley (1846–1924), Bernard Bosanquet (1848–1923), J. H. Muirhead (1855–1940), , H. H. Joachim (1868–1938), A. E. Taylor (1869–1945), R. G. Collingwood (1889–1943), G. R. G. Mure (1893–1979) and Michael Oakeshott.

[158] As such, Green accepts the reality of biological bodies when he writes that "in the process of our learning to know the world, an animal organism, which has its history in time, gradually becomes the vehicle of an eternally complete consciousness.

[179] Defenders of a Theistic and idealistic personalism include Borden Parker Bowne (1847–1910), Andrew Seth Pringle-Pattison (1856–1931), Edgar S. Brightman and George Holmes Howison (1834–1916).

[180][179] However, other personalists like British idealist J. M. E. McTaggart and Thomas Davidson merely argued for a community of individual minds or spirits, without positing a supreme personal deity who creates or grounds them.

[181][182][183] Similarly, James Ward (1843–1925) was inspired by Leibniz to defend a form of pluralistic idealism in which the universe is composed of "psychic monads" of different levels, interacting for mutual self-betterment.

[179] Bowne's students, like Edgar Sheffield Brightman, Albert C. Knudson (1873–1953), Francis J. McConnell (1871–1953), and Ralph T. Flewelling (1871–1960), continued to develop his personal idealism after his death.

[105] Physicist Milton A. Rothman has written that idealism in incompatible with science and is not considered an empirical system of knowledge unlike realism which is pragmatical and makes testable predictions.