Allen Ginsberg

He vigorously opposed militarism, economic materialism, and sexual repression, and he embodied various aspects of this counterculture with his views on drugs, sex, multiculturalism, hostility to bureaucracy, and openness to Eastern religions.

[12] His poem "September on Jessore Road" drew attention to refugees fleeing the 1971 Bangladeshi genocide, exemplifying what literary critic Helen Vendler described as Ginsberg's persistent opposition to "imperial politics" and the "persecution of the powerless".

[22] In 1943, Ginsberg graduated from Eastside High School and briefly attended Montclair State College before entering Columbia University on a scholarship from the Young Men's Hebrew Association of Paterson.

"[46] In Ginsberg's first year at Columbia he met fellow undergraduate Lucien Carr, who introduced him to a number of future Beat writers, including Jack Kerouac, William S. Burroughs, and John Clellon Holmes.

As a Barnard student, Elise Cowen extensively read the poetry of Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, when she met Joyce Johnson and Leo Skir, among other Beat players.

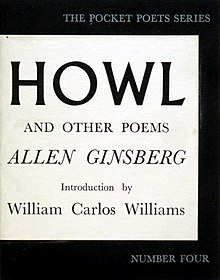

[citation needed] Through his association with Elise Cowen, Ginsberg discovered that they shared a mutual friend, Carl Solomon, to whom he later dedicated his most famous poem "Howl."

An account of that night can be found in Kerouac's novel The Dharma Bums, describing how change was collected from audience members to buy jugs of wine, and Ginsberg reading passionately, drunken, with arms outstretched.

The event attracted an audience of 7,000, who heard readings and live and tape performances by a wide variety of figures, including Ginsberg, Adrian Mitchell, Alexander Trocchi, Harry Fainlight, Anselm Hollo, Christopher Logue, George MacBeth, Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Michael Horovitz, Simon Vinkenoog, Spike Hawkins and Tom McGrath.

[69] Later in his life, Ginsberg formed a bridge between the beat movement of the 1950s and the hippies of the 1960s, befriending, among others, Timothy Leary, Ken Kesey, Hunter S. Thompson, and Bob Dylan.

[72] Ginsberg helped Trungpa and New York poet Anne Waldman in founding the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado.

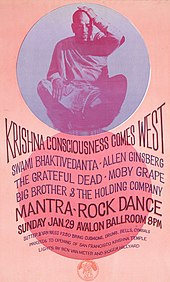

After learning that A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, the founder of the Hare Krishna movement in the Western world had rented a store front in New York, he befriended him, visiting him often and suggesting publishers for his books, and a fruitful relationship began.

[75] Despite disagreeing with many of Bhaktivedanta Swami's required prohibitions, Ginsberg often sang the Hare Krishna mantra publicly as part of his philosophy[76] and declared that it brought a state of ecstasy.

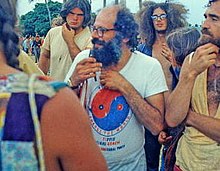

"[85] At the 1967 Human Be-In in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park, the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, and the 1970 Black Panther rally at Yale campus Allen chanted "Om" repeatedly over a sound system for hours on end.

[87] In spite of Ginsberg's attraction to Eastern religions, the journalist Jane Kramer argues that he, like Whitman, adhered to an "American brand of mysticism" that was "rooted in humanism and in a romantic and visionary ideal of harmony among men.

In 1989, Ginsberg appeared in Rosa von Praunheim's award-winning film Silence = Death about the fight of gay artists in New York City for AIDS-education and the rights of HIV infected people.

Ginsberg continued to help his friends as much as he could: he gave money to Herbert Huncke out of his own pocket, regularly supplied neighbor Arthur Russell with an extension cord to power his home recording setup,[95][96] and housed a broke, drug-addicted Harry Smith.

With the exception of a special guest appearance at the NYU Poetry Slam on February 20, 1997, Ginsberg gave what is thought to be his last reading at The Booksmith in San Francisco on December 16, 1996.

After returning home from the hospital for the last time, where he had been unsuccessfully treated for congestive heart failure, Ginsberg continued making phone calls to say goodbye to nearly everyone in his address book.

Ginsberg used gritty descriptions and explicit sexual language, pointing out the man "who lounged hungry and lonesome through Houston seeking jazz or sex or soup."

Other signers and RESIST members included Mitchell Goodman, Henry Braun, Denise Levertov, Noam Chomsky, William Sloane Coffin, Dwight Macdonald, Robert Lowell, and Norman Mailer.

[112] Ginsberg talked openly about his connections with communism and his admiration for past communist heroes and the labor movement at a time when the Red Scare and McCarthyism were still raging.

[citation needed] Ginsberg was a supporter and member of the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA), a pedophilia and pederasty advocacy organization in the United States that works to abolish age of consent laws and legalize sexual relations between adults and children.

[124][citation needed] Saying that he joined the organization "in defense of free speech",[125] Ginsberg stated: "Attacks on NAMBLA stink of politics, witchhunting for profit, humorlessness, vanity, anger and ignorance ...

[126] In 1994, Ginsberg appeared in a documentary on NAMBLA called Chicken Hawk: Men Who Love Boys (playing on the gay male slang term 'chickenhawk'), in which he read a "graphic ode to youth".

In her 2002 book Heartbreak, Andrea Dworkin claimed Ginsberg had ulterior motives for allying with NAMBLA: In 1982, newspapers reported in huge headlines that the Supreme Court had ruled child pornography illegal.

[133][135] Ginsberg wrote many essays and articles, researching and compiling evidence of the CIA's alleged involvement in drug trafficking, but it took ten years, and the publication of McCoy's book in 1972, before anyone took him seriously.

[144] Ginsberg later acknowledged in various publications and interviews that behind the visions of the Francis Drake Hotel were memories of the Moloch of Fritz Lang's film Metropolis (1927) and of the woodcut novels of Lynd Ward.

[41] Moloch has subsequently been interpreted as any system of control, including the conformist society of post-World War II America, focused on material gain, which Ginsberg frequently blamed for the destruction of all those outside of societal norms.

[150][122] Carl Solomon introduced Ginsberg to the work of Antonin Artaud (To Have Done with the Judgement of God and Van Gogh: The Man Suicided by Society), and Jean Genet (Our Lady of the Flowers).

McClatchy's barbed eulogies define the essential difference between Ginsberg ("a beat poet whose writing was [...] journalism raised by combining the recycling genius with a generous mimic-empathy, to strike audience-accessible chords; always lyrical and sometimes truly poetic") and Kerouac ("a poet of singular brilliance, the brightest luminary of a 'beat generation' he came to symbolise in popular culture [...] [though] in reality he far surpassed his contemporaries [...] Kerouac is an originating genius, exploring then answering—like Rimbaud a century earlier, by necessity more than by choice—the demands of authentic self-expression as applied to the evolving quicksilver mind of America's only literary virtuoso [...]").