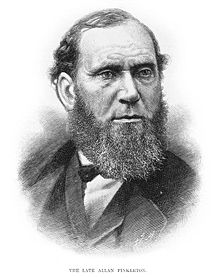

Allan Pinkerton

[9] As early as 1844, Pinkerton worked for the Chicago abolitionist leaders, and his Dundee home was a stop on the Underground Railroad.

[10] Pinkerton first became interested in criminal detective work while wandering through the wooded groves around Dundee, looking for trees to make barrel staves, when he came across a band of counterfeiters,[11] who may have been affiliated with the notorious Banditti of the Prairie.

[12] When the Civil War began, Pinkerton served as head of the Union Intelligence Service during the first two years, heading off an alleged assassination plot in Baltimore, Maryland while guarding Abraham Lincoln on his way to Washington, D.C., as well as providing estimates of Confederate troop numbers to General George B. McClellan when he commanded the Army of the Potomac.

[14] Military historians have been strongly critical of the intelligence Pinkerton provided for the Union Army, which for the most part was undigested raw data.

"[15] Pinkerton's estimates of Rebel troop numbers, derived from his credulous interrogations of Confederate prisoners, deserters, refugees, escaped slaves ("contrabands"), and civilians unused to counting large bodies of men, badly exaggerated the size of those formations, sometimes almost doubling their actual strength.

Pinkerton's numbers caused McClellan to consistently believe that he was drastically outnumbered by the Confederate forces he faced.

[16][17][a] On the other hand, Edwin C. Fishel in The Secret War for the Union and James Mackay in Allan Pinkerton: The First Private Eye argue that the troop strength figures which Pinkerton passed on to McClellan were relatively accurate, and that McClellan himself held primary responsibility for inflating those numbers to wildly unrealistic levels.

[18][19] Following Pinkerton's services for the Union Army, he continued his pursuit of train robbers, including the Reno Gang.

[20] In 1872, the Spanish Government hired Pinkerton to help suppress a revolution in Cuba which intended to end slavery and give citizens the right to vote.

[21] If Pinkerton knew this, then it directly contradicts statements in his 1883 book The Spy of the Rebellion, where he professes to be an ardent abolitionist and hater of slavery.

[23] Contemporary reports give conflicting causes, such as that he succumbed to a stroke – he had a year earlier – or to malaria, which he had contracted during a trip to the Southern United States.

[24] At the time of his death, he was working on a system to centralize all criminal identification records; such a database is now maintained by the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Most historians believe that Allan Pinkerton hired ghostwriters, but the books nonetheless bear his name and no doubt reflect his views.