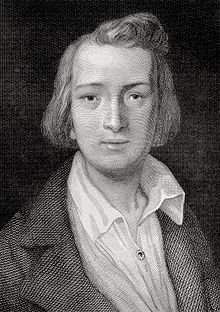

Heinrich Heine

He is best known outside Germany for his early lyric poetry, which was set to music in the form of Lieder (art songs) by composers such as Robert Schumann and Franz Schubert.

Heine was a third cousin once removed of philosopher and economist Karl Marx (1818–1883), also born to a German Jewish family in the Rhineland, with whom he became a frequent correspondent in later life.

He glossed over the negative aspects of French rule in Berg: heavy taxation, conscription, and economic depression brought about by the Continental Blockade, which may have contributed to his father's bankruptcy.

The university had engaged the famous literary critic and thinker August Wilhelm Schlegel as a lecturer and Heine heard him talk about the Nibelungenlied and Romanticism.

Other events conspired to make Heine loathe this period of his life: he was expelled from a student fraternity due to anti-Semitism, and he heard the news that his cousin Amalie had become engaged.

[13] Heine also made valuable acquaintances in Berlin, notably the liberal Karl August Varnhagen and his Jewish wife Rahel, who held a leading salon.

[14] During his time in Berlin Heine also joined the Verein für Cultur und Wissenschaft der Juden, a society which attempted to achieve a balance between the Jewish faith and modernity.

Before finding work, Heine visited the North Sea resort of Norderney which inspired the free verse poems of his cycle Die Nordsee.

No one expected it to become one of the most popular books of German verse ever published, and sales were slow to start with, picking up when composers began setting Heine's poems as Lieder.

Du siehst mich an wehmütiglich, Und schüttelst das blonde Köpfchen; Aus deinen Augen schleichen sich Die Perlentränentröpfchen.

The blue flower of Novalis, "symbol for the Romantic movement", also received withering treatment from Heine during this period, as illustrated by the following quatrains from Lyrisches Intermezzo:[25] Am Kreuzweg wird begraben Wer selber brachte sich um; dort wächst eine blaue Blume, Die Armesünderblum'.

Heine became increasingly critical of despotism and reactionary chauvinism in Germany, of nobility and clerics but also what he viewed as “narrow mindedness” of ordinary people and of the rising German form of nationalism, especially in contrast to the French and the revolution.

Nevertheless, he made a point of stressing his love for his Fatherland: Plant the black, red, gold banner at the summit of the German idea, make it the standard of free mankind, and I will shed my dear heart's blood for it.

[28] On his return to Germany, Cotta, the liberal publisher of Goethe and Schiller, offered Heine a job co-editing a magazine, Politische Annalen, in Munich.

He felt de Staël had portrayed a Germany of "poets and thinkers", dreamy, religious, introverted and cut off from the revolutionary currents of the modern world.

"[41] Heine and his fellow radical exile in Paris, Ludwig Börne, had become the role models for a younger generation of writers who were given the name "Young Germany".

This led to the emergence of popular political poets (so-called Tendenzdichter), including Hoffmann von Fallersleben (author of Deutschlandlied, the German anthem), Ferdinand Freiligrath and Georg Herwegh.

Heine's mode was satirical attack: against the Kings of Bavaria and Prussia (he never for one moment shared the belief that Frederick William IV might be more liberal); against the political torpor of the German people; and against the greed and cruelty of the ruling class.

Ultimately Heine's ideas of revolution through sensual emancipation and Marx's scientific socialism were incompatible, but both writers shared the same negativity and lack of faith in the bourgeoisie.

Indeed, with fear and terror I imagine the time, when those dark iconoclasts come to power: with their raw fists they will batter all marble images of my beloved world of art, they will ruin all those fantastic anecdotes that the poets loved so much, they will chop down my Laurel forests and plant potatoes and, oh!, the herbs chandler will use my Book of Songs to make bags for coffee and snuff for the old women of the future – oh!, I can foresee all this and I feel deeply sorry thinking of this decline threatening my poetry and the old world order – And yet, I freely confess, the same thoughts have a magical appeal upon my soul which I cannot resist ....

It tells the story of the hunt for a runaway bear, Atta Troll, who symbolises many of the attitudes Heine despised, including a simple-minded egalitarianism and a religious view which makes God in the believer's image.

His review of the musical season of 1844, written in Paris on 25 April 1844, is his first reference to Lisztomania, the intense fan frenzy directed toward Franz Liszt during his performances.

Heine's review subsequently appeared on 25 April in Musikalische Berichte aus Paris and attributed Liszt's success to lavish expenditures on bouquets and to the wild behaviour of his hysterical female "fans".

Mich wird umgeben Gotteshimmel, dort wie hier, Und als Totenlampen schweben Nachts die Sterne über mir.

Should that subduing talisman, the cross, be shattered, the frenzied madness of the ancient warriors, that insane Berserk rage of which Nordic bards have spoken and sung so often, will once more burst into flame.

Then the ancient stony gods will rise from the forgotten debris and rub the dust of a thousand years from their eyes, and finally Thor with his giant hammer will jump up and smash the Gothic cathedrals.

They include Robert Schumann (especially his Lieder cycle Dichterliebe), Friedrich Silcher (who wrote a popular setting of "Die Lorelei", one of Heine's best known poems), Franz Schubert, Franz Liszt, Felix Mendelssohn, Fanny Mendelssohn, Johannes Brahms, Hugo Wolf, Richard Strauss, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Edward MacDowell, Clara Ross, Elise Schlick, Elise Schmezer, Sophie Seipt, Charlotte Sporleder, Maria Anna Stubenberg, Pauline Volkstein, Clara Schumann and Richard Wagner; and in the 20th century Lord Berners, Yehezkel Braun, Hans Werner Henze, Paul Lincke, Nikolai Medtner, Carl Orff, Harriet P. Sawyer, Marcel Tyberg[79] and Lola Carrier Worrell.

Wilhelm Killmayer set 37 of his poems in his song book Heine-Lieder, subtitled Ein Liederbuch nach Gedichten von Heinrich Heine, in 1994.

While at first the plan met with enthusiasm, the concept was gradually bogged down in anti-Semitic, nationalist, and religious criticism; by the time the fountain was finished, there was no place to put it.

In Israel, the attitude to Heine has long been the subject of debate between secularists, who number him among the most prominent figures of Jewish history, and the religious who consider his conversion to Christianity to be an unforgivable act of betrayal.