Altair 8800

The Altair 8800 is a microcomputer designed in 1974 by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems (MITS) and based on the Intel 8080 CPU.

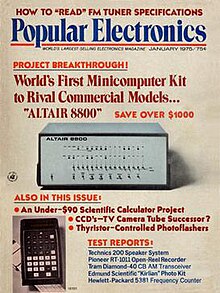

[3] Interest in the Altair 8800 grew quickly after it was featured on the cover of the January 1975 issue of Popular Electronics[4] and was sold by mail order through advertisements there, in Radio-Electronics, and in other hobbyist magazines.

According to the personal computer pioneer Harry Garland, the Altair 8800 was the product that catalyzed the microcomputer revolution of the 1970s.

The November 1970 issue of Popular Electronics featured the Opticom, a kit from MITS that would send voice over an LED light beam.

Electronic Arrays had just announced the EAS100, a set of six large scale integrated (LSI) circuit chips that would make a four-function calculator.

The change in editorial staff upset many of their authors, and they started writing for a competing magazine, Radio-Electronics.

(Popular Electronics gave Jerry Ogden a column, Computer Bits, starting in June 1975.

In a last-ditch attempt to save MITS, Roberts decided to do something that was impossible at the time: create a personal computer kit for hobbyists.

[16] Ed Roberts and his head engineer, Bill Yates, finished the first prototype in October 1974 and shipped it to Popular Electronics in New York via the Railway Express Agency.

The finished Altair computer had a completely different circuit board layout than the prototype shown in the magazine.

[17] The January 1975 issue was registered on November 29, 1974,[18] and began appearing on newsstands on December 19, 1974—during the week before Christmas of 1974[19][16][20][21]—at which point the kit was officially (if not yet practically) available for sale.

Ed Roberts was busy finishing the design and left the naming of the computer to the editors of Popular Electronics.

"[22] The Star Trek episode is probably "Amok Time", as this is the only one from The Original Series which takes the Enterprise crew to Altair (Six).

[24] At that time, Intel's main business was selling memory chips by the thousands to computer companies.

[26][27] Seizing the opportunity to be ahead of computers of the time, MITS began development of the Altair 8800 in the summer of 1974, about 2 months after the release of the Intel 8080.

It was functionally similar to the Altair 8800 but it was a commercial grade system with a wide selection of peripherals and development software.

The sales force should sell the Intellec system based on its merits and that no one should make derogatory comments about valued customers like MITS.

[31] The "cosmetic defect" rumor has appeared in many accounts over the years although both MITS and Intel issued written denials in 1975.

[32] For a decade, colleges had required science and engineering majors to take a course in computer programming, typically using the FORTRAN or BASIC languages.

It was easier to assemble: The Altair required 60 wire connections between the front panel and the motherboard (backplane).

The IMSAI also had a larger power supply to handle the increasing number of expansion boards used in typical systems.

The IMSAI advantage was short lived because MITS had recognized these shortcomings and developed the Altair 8800B, which was introduced in June 1976.

Another problem facing Roberts was that the parts needed to make a truly useful computer were not available, or would not be designed in time for the January launch date.

No particular level of thought went into the design, which led to disasters such as shorting from various power lines of differing voltages being located next to each other.

A deal on power supplies led to the use of +8 V and ±18 V,[citation needed] which had to be locally regulated on the cards to TTL (+5 V) or RS-232 (±12 V) standard voltage levels.

The front panel, which was inspired by the Data General Nova minicomputer, included a large number of toggle switches to feed binary data directly into the memory of the machine, and a number of red LEDs to read those values back out.

Ed Roberts received a letter from Traf-O-Data asking whether he would be interested in buying what would eventually be the BASIC programming language for the machine.

In fact the letter had been sent by Bill Gates and Paul Allen from the Boston area, and they had no BASIC yet to offer.

When they called Roberts to follow up on the letter he expressed his interest, and the two started work on their BASIC interpreter using a self-made simulator for the 8080 on a PDP-10 mainframe computer.